Cocteau Twins

Sugar hiccup makes the earth tough and tumble

Cocteau Twins were one of the first major bands to be categorized under “dream pop,” essentially pop-leaning alternative music with an emphasis on production techniques that created a friendly psychedelic (dreamy) effect. They were also the best because their version of dream pop wasn’t purged of nightmares: it was an interesting balance of light and dark that made them unique. The countless imitators that came afterwards dropped the darkness, and none of them could imitate Liz Fraser’s vocals anyway.

If you’ve heard anything about Cocteau Twins, it’s likely praise for Liz Fraser. Not only was she capable of great power and range, she was also unique in her ability to spin words into clouds—really putting the dream in dream pop—or break them apart into hiccups. Some of her words aren’t even in English—sometimes her sources would be languages she couldn’t read; others would be languages not yet spoken by anyone but her—and even when they were in English, she would phrase the lyrics in such a way that they wouldn’t seem that way. And they’d also be loaded with hooks, memorable and delightful little melodies that would invite you to want to learn more about this special alien language.

That said, for all the praise that Fraser receives—and deserves—I think we have all done guitarist Robin Guthrie a huge disservice. Guthrie possessed an ability to harness guitar feedback into physical bracing noise on their early records—he’s that nightmare fuel, the darkness to her light, and had he been making those sounds just five years later, people would have filed Cocteau Twins under shoegaze because of him—and after 1985, he switched styles to gentler melody-making and thoughtful textures (guitars as synths or the other way around) without missing a step. Not only that, but Guthrie was one of the very few people in the 1980s to recognize a drum machine as just that, a machine, rather than something that could imitate a person, hence why the drum programming on their early records is so loud and bracing and monolithic. Without Fraser, there’d be no Cocteau Twins, yes, but I’d say the same about Guthrie. The pair were one of the best guitarist-vocalist combinations of the decade.

Here’s the guide:

Off its acclaim, most people start their Cocteau Twins’ journey with Heaven or Las Vegas, so there’s a huge shock for anyone who immediately backtracks to the start of their career to be greeted by Liz Fraser singing—very clearly, in English—“Blood woman / Blood bitch” like a vampire slowly making her way towards you. Listeners that start with Garlands and go chronologically won’t have the same fun! Opener “Blood Bitch” is their first great song with the screech of the Guthrie’s guitar, Heggie’s Joy Division bass and the drum machine beat making it sound like we’re shooting down the highway in the dead of night driving away from something, which turns out to be Fraser at her most frightening. “Wax and Wane” has the album’s most direct hook, but alas, the album as a whole gets wearying. I’m tempted to compare this to New Order’s Movement in that both debut albums sound like other people; New Order naturally sounding like Joy Division, while Cocteau Twins here sound like a lesser version of Siouxsie and the Banshees — although I’ll state here that I wish more people tried to imitate them, a widely respected band that should have been worshipped way more given their magnificent output in the 1980s. Part of the problem is that founding member and bassist Will Heggie’s playing chews up too much scenery for what Guthrie and Fraser need, and they’d be better without him.

Heggie would stay with the band until 1983’s Peppermint Pig, notable for being produced by the Associates’ Alan Rankin before leaving to form Lowlife, making the band sound closer to the Cure now. Robin Guthrie, in an interview with Sounds Magazine, described the EP as “Shit,” elaborating, “We’d never used a producer before, so we thought it might be good to have someone on the outside try to help, but it [didn’t] work out, because he wasn’t interested, he didn’t like the music to start with.” Notably, they’d never ask for outside help for production again.

And so Guthrie himself produces Head Over Heels to make it sound like it was recorded in an abandoned cathedral. There’s a horrifying pummel in the drum machines, and the guitar chords arrive like massive waves. But he’s careful to make sure the additional textures, and there are a few here, each of them a surprise—the saxophone in “Five Ten Fiftyfold” or the circular steel drum pattern on “The Tinderbox (of a Heart)”—shimmer despite often being buried in the mix. The acoustic guitar of “In the Gold Dust Rush” sounds absolutely magnificent, achieving the gold dust rush promised by its title, and the song should be noteworthy for opening with the “Be My Baby” drum pattern a few years before Jesus and the Mary Chain got there. And of course, there’s also “Sugar Hiccup,” a title that essentially describes their entire sound if you had to boil it down to two words, looking forward to their more cherry-sweet songs to come. 1983 saw albums from the Chameleons, the Fall, Echo and the Bunnymen, and the best U2 album, and yet despite all of that, I think Cocteau Twins released the best post-punk album of that year, which only sounds weird because it’s also the best dream pop album of that same year. Early Cocteau Twins mixed up two seemingly disparate genres so effortlessly!

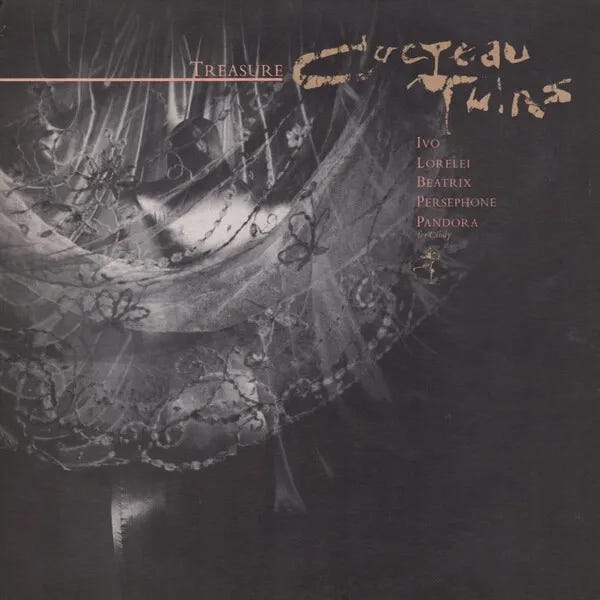

Treasure is their best album because it pulls from Head Over Heels’ darkness and looks forward to Heaven or Las Vegas’ brightness, with even some Victorialand to go around. Not only is every song exactly what the title suggests they’ll be, but the album is well-sequenced: two hooky pop songs at the start, two siren songs to follow, Fraser guiding you back to safety with “Pandora”; the band letting you drift off with “Otterley” but waking you up for Christmas morning on “Donimo.” On that last ote, no wonder that the two Christmas songs that the band made on the Snow single in 1993 would be so good: they had already perfected holiday songs early on. Treasure will be the last time that the drum programming has such presence on a Cocteau Twins record, and I’m not even thinking of “Persephone” when it’s heaviest: note the drum-roll at the 0:42 mark of “Lorelei,” like a machine glitching out, or even the loud mixing of the drum smacks on “Pandora” that makes the song feel like we’re watching a deeply intimate slow dance between two lovers as fireworks hit the sky in slow motion above them. Interestingly, 4AD label-head Ivo Watts-Russell tried to get Brian Eno to produce the album with Daniel Lanois, but Eno felt that the band didn’t need them — I agree: it’s hard to imagine this album being any better with Eno (although I would be tempted to hear an Eno-produced version of Victorialand). Side note: Arca made incredible use of a sample of “Beatrix” for her Entrañas mixtape by having a clip of Gainsbourg going “For a boy to look like a girl is degrading / Because you think that being a girl is degrading” lead into it, which Ghersi bolsters with pummeling industrial drums — it’s my favourite moment in Arca’s discography.

Bassist Simon Raymonde was pulled to help This Mortal Coil—4AD’s supergroup project that made three albums, none of them nearly as good as their debut EP where Liz Fraser covered Tim Buckley, and the last two double albums are both downright stinky—and so Fraser and Guthrie recorded Victorialand without him. They change the sound completely, with Guthrie swapping out the heavy drum machines because they’re not appropriate for ambient world-building: the album is named after a part of Antarctica, and many of the song titles allude to the snowy region that Fraser and Guthrie explore with softer textures. Warm snow though: Fraser can’t help herself. “Lazy Calm” doesn’t even have a beat until halfway through, and when it does, it doesn’t so much “snap” into focus but “shift,” and the way the instruments imitate Fraser’s vocals from 3:45 - 3:55 is magical. Guthrie’s synths like the first snowfall on “Fluffy Tufts”; at once melodic and rhythmic in lieu of a single beat (although Guthrie adds some bass notes here and there, essentially proving that they didn’t need Raymonde all that much). What Guthrie is doing in the first minute of “Feet-Like Fins” is unbelievable: synths shimmering like South Asian acoustic instruments. Richard Thomas’ additions of saxophone (“Lazy Calm”) and tablas (“Feet-Like Fins”) are welcome little textures even if they place the album firmly in the 1980s.

The Moon and the Melodies is a one-off side project between all three members of the Cocteau Twins and Harold Budd (Brian Eno collaborator and early ambient composer), so theoretically, it should be a match made in heaven: you’d think they’d just make songs in the vein of the second half of Eno’s Before and After Science. But they don’t. George Starostin attributes the album’s shortcomings to Budd’s stasis being at odds with Cocteau Twins’ dynamics, but I think that’s simplifying the true issue which is that the album ultimately plays like four songs by Cocteau Twins and four songs by Harold Budd, and very little suggests actual collaboration. Here’s proof: “Memory Gongs” is just a slightly different version of “Flowered Knife Shadows” from Budd’s own album that same year, Lovely Thunder; but the credits claim all four people wrote this one, whereas the credits on Lovely Thunder say it was written by Budd by himself. The only exception to this rule is the first song, where Budd’s piano line is “looped” underneath a Cocteau Twins song. Sure, sometimes Guthrie’s guitar lines sound like they could have possibly been written by Budd (“She Will Destroy You”) but it’s also possible that they’re Guthrie’s ideas in the first place. So don’t fret if you missed it in Cocteau Twins’ own discography because it’s attributed to the individual members of the band and not the band instead (itself a strange decision).

It’s my personal theory that because Blue Bell Knoll was their first album to get distributed in America via Capitol Records, Guthrie really smoothed out the production to get a bigger audience overseas, making the album feel very ‘samey.’ That said, “Carolyn’s Fingers” gets my vote for the best song of its year and the best song they’ve ever done. 0:30 - 0:40 is peak Fraser, culminating with a giggle and then a sudden “FRAM” burst might be my favourite single moments in modern pop vocals; it gives me goosebumps just thinking about it. The album was recorded at a time when Fraser and Guthrie were going to have a baby together, and songs like “For Phoebe Still a Baby” have an intimacy to them that they never explored before, like we get to hear Fraser singing to her child still in the womb. Elsewhere, the harpsichord runs of the title track is reminiscent of the eclectic turns on Head Over Heels, while “A Kissed Out Red Floatboat”—a minor complaint here, which is that the song titles read as parodies of Cocteau Twins—and the glitchy “A Kissed Out Red Floatboat” (put the first four seconds out under the name ‘Autechre’ and no one would think twice) are the last instrumental surprises to appear on any Cocteau Twins record.

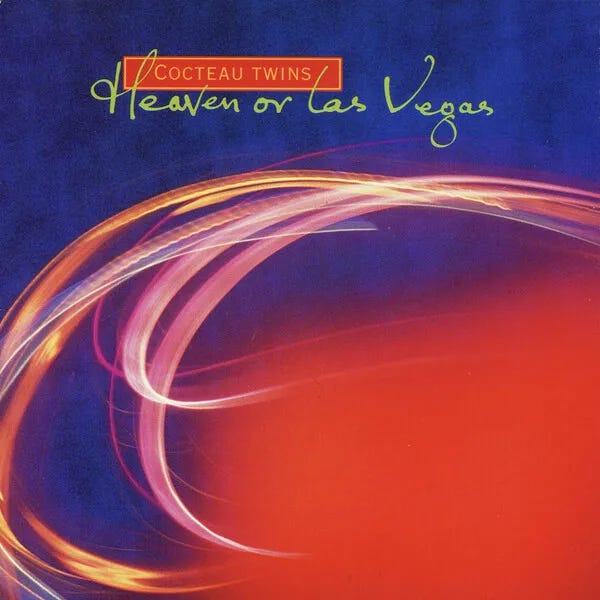

Which is why I so heavily disagree with the practically-unanimous consensus that Heaven or Las Vegas is their best album, this is the rare music-related hot takes hill I’ll die on: it’s not as consistent as Treasure or Victorialand, and its highs aren’t as high as Head Over Heels or Blue Bell Knoll. It’s still a great album, of course. The title track is their clearest and cleanest and most direct—“Singing on the famous street” is sung in English for once—and I actually do get flashes of lights on busy streets in Guthrie’s guitar line alone, and I love the little back and forth dance that Simon Raymonde does with the drum machine; the effect isn’t just walking down a Las Vegas street but spinning down one until the lights are a blur, reminiscent of the cover art’s swirl of nebula radiantly warmth. And of course, I adore the falsetto on “Cherry-Coloured Funk,” and Fraser’s high notes at the end of “I Wear Your Ring” (“Fie, fie, fie…”), and, especially, the overdubbed vocals in the choruses of “Frou-frou Foxes in Midsummer Fires”—“Pulled roundahhhhhh...pulled roundahhhh…”—that make that far less interesting verses worth wading through. But some of these songs feel like less-special versions that we’ve already heard, and I frankly detest that most of the album’s best owes practically exclusively to Fraser. I like Raymonde’s slightly-funky bass on “Pitch the Baby,” and the texture of the synths on “I Wear Your Ring,” but altogether, Guthrie is really phoning it in here. Especially heartbreaking is that the drum programming—once the third ‘voice’ in the band—is reduced to these painfully generic, unvaried tippy-tappy beats. Put the beat from “Iceblink Luck” under U2’s songs on Achtung Baby and no one would bat an eye.

The Cocteau Twins had a tight discography—only eight albums released under their name, and one collaboration—but they released a steady stream of material through EPs. The songs in these mini-packages after Peppermint Pig never feel like filler because Fraser is simply too good for a word like that to apply, and some songs are, in fact, career highlights, particularly the title track from The Spangle Maker (one of their few songs with a climax, and the words during which have a huge emotional bend to them; “We scattered and didn’t bond…”; “I whistle and there you hide”), “Quisquose” from Aikea-Guinea (merry-go-round overdubbed vocals over darkly-shaded piano chords), and the title track from Love’s Easy Tears (which feels like a response to their fellow countrymen Jesus and the Mary Chain’s “Just Like Honey” with a slightly re-jigged “Be My Baby” drum beat, and the strangely lo-fi production gives it a noisy layer). And though the two songs on the Iceblink Luck EP aren’t better than anything on the parent album, I’d still recommending looking for “Watchlar” for far more interesting drum textures than anything on that album.

Robin Guthrie once said “most of the people who make new age music are 50 and balding” as a means of distancing the band from the tag which was increasingly applied to them from Victorialand-onwards. If Guthrie didn’t want his music to be classified as such, then he should have tried a little harder on their last two albums, Four-Calendar Café and Milk and Kisses. It’s particularly heartbreaking to hear Guthrie, once so potent and imaginative to be reduced to these Am and Em chords—a good comparison would be R.E.M.’s Peter Buck, who also stopped bothering with barre chords around this time—likely because he was trying to sober up after years of heavy drug addiction. “Bluebeard” is the only time he comes up with a good guitar line on Four-Calendar Café, and the alt-country vibe suggests a new avenue that they could have explored in the 1990s — but Toronto’s Cowboy Junkies had already milked that sound dry by 1993. I adore the melody of “Rilkean Heart” which I glossed over until I heard the piano ballad version on the Twinlights EP, but these two albums are what I dislike from so much dream pop that came after them. Those early Cocteau Twins records had so much blood and sinew in them, while still being super dreamy! Now, it’s all just reverberated arpeggios.

Garlands - B Head Over Heels - A- Treasure - A Victorialand - A- The Moon and the Melodies - B- Blue Bell Knoll - A- Heaven or Las Vegas - A- Four-Calendar Café - B- Milk and Kisses - B-

Good work. Two things for me about Cocteau. First, I'm reminded about something that you've written before, that there is a sort of musicality to language, that transcends above what the lyrics are actually saying. We don't particularly understand what Liz Fraser is saying, sure, but we still emote with it, because she possesses a beautiful voice, and in a sense, we get to figure out ourselves what it means to us.

Second, Fraser's vocals are run through tons of processing, layering, and other production tricks on (most) of the Cocteau Twins' albums. Now, I think that it does work most of the time, but I do *really* like how Fraser's voice sounds without any extra processing. Part of why Massive Attack's Mezzanine is one of my favorite albums, is that you get to hear Fraser's voice without any of the layering on three songs, with her at least trying to be intelligible. It's really beautiful, probably one of the best vocal performances of all time, so I wonder how Cocteau would have turned out if they were more Singer-Songwriter rather than Dream Pop/Shoegaze.