David Bowie (Pt. 1)

Golden Years (1967-1979)

David Bowie represented the shift away from band culture in rock music from the 1960s (The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, The Who) and towards individuality. Hence why so many people mourned his passing: it’s easier to identify with a human being than a group, especially one who helped us embrace our own kookiness.

Here’s what made Bowie great: for starters, he was a tremendous singer, theatrical like his image but with a willingness to screech and stretch his voice (which, all in all, I wish he did way more of) that clearly set him apart from his glam rock contemporaries like T. Rex’s Marc Bolan, Roxy Music’s Bryan Ferry and Lou Reed. Further separating him from all the other 70s’ rock-stars was that he hard-pivoted into electronic/ambient music just as glam rock was at its most decadent and boring, eventually opening the doors for U2 and Radiohead to do the same decades later. He was musically omnivorous beyond that: soul, industrial and even drum and bass; the crowning of Bowie as the ‘Chameleon of Pop’ is well-earned. He also had access to some geniuses: Carlos Alomar, Robert Fripp and Mick Ronson are all incredible guitarists; Brian Eno had a minor role on the ‘Berlin Trilogy’ (contrary to popular belief, Eno had no hand in producing those records); Tony Visconti isn’t praised enough as a producer: there’s so much space on the best Bowie albums.

Unlike his British Invasion heroes, David Bowie did not arrive fully-formed, nor did he become a star overnight. Quite the opposite, actually: “Space Oddity” peaked only at #5 on the UK charts when it was released at the tail-end of the 1960s, and Bowie was probably deemed as a one-hit wonder until 1972 where he scored another hit with “Starman” (“Changes” didn’t chart at all). And so, it took him about 5 years to become a household name; only after that was “Life on Mars?” retroactively released as a hit and then “Space Oddity” was re-released, nabbing Bowie a #1 and becoming Bowie’s first hit in the US as well (at #15). It’s weird to believe now but during the early-70s, Marc Bolan was bigger than Bowie, with T. Rex touted as the next Stones/Dylan and sporting multiple chart-topping singles. Decades later, no one remembers Bolan (at least, that’s my personal experience living here in Canada) while Bowie is remembered fondly as both a musician and a great liberator. (Also, a plug somewhere that both men were hot.)

Having been active across six (!!!) different decades, there’s a lot to be discussed, which I’m going to split across two posts for ease of reading. No scores, no rankings, just words, although a digital cookie to anyone who can guess the top 5. So without further ado, let’s get into them:

David Bowie (1967) will be the hardest Bowie album to get a read on because everyone interested in Bowie backtracked to this one from somewhere else instead of starting here. Even if you only know Bowie from his reputation and somehow avoided hearing any of his hits, you’ve already formed an idea of Bowie that this album won’t come close to: an album with barely a hint of rock, it’s all music hall! The last two songs aren’t very interesting, and many of the arrangements and/or the songs themselves are much too twee like those harmonizing vibes and syrupy strings on “Love You Till Tuesday,” which is the best song regardless, driven by a rock groove from bassist Dek Fearnley. I like “Rubber Band” because Bowie’s pain-stricken “Oh!” after he sings “You're playing my tune out of tune” (which strangely happens only once when it should have been the chorus) and “She’s Got Medals” will be interesting for historians in beating out the Kinks and Lou Reed about a woman who passes herself off as a man (“Her mother called her Mary, but she changed her name to Tommy […] / She went and joined the army, passed the medical, don’t ask me how it’s done”). A better album than the next one, if you could believe it, but still not that good.

David Bowie (1969) is the album that contains “Space Oddity” and because you can get that song off of every Bowie compilation and regularly on every radio station and even performed in space, you don’t need this album. “Unwashed And Somewhat Slightly Dazed” and “Cygnet Committee” are long and not worth it; “Letter to Hermione” is pleasant although Bowie’s vocals are surprisingly scratchy as he tries to plumb an emotional depth that just isn’t there; “Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud” attempts a “Hey Jude”-style climax but doesn’t come close, and not helping is that odd toy drum sound at the peak instead of something with more ‘oomph.’ As for “Space Oddity,” if I’ve heard it once, I’ve heard it a million times: that drum sound smacking every 3rd beat is hideous. What I like about it most are the colours: Bowie’s droning Stylophone and the flutes during the bridge (“For here am I sitting in my tin can”) that makes me think of the clarinet in the bridge of Simon & Garfunkel’s “America.” (I’d personally rather listen to Elton John’s “Rocket Man,” clearly was inspired by this song and also produced by the same person.)

The Man Who Sold the World represents the first major shift in Bowie’s career but not as dramatic as some of his later ones: here, he switches out some of the acoustic and chamber instruments (only to bring them back in the following album) for more electric ones. For example, opener “The Width of a Circle” has a particularly doomy riff that aligns it with so much hard rock/heavy blues that was popular around this time; the swooping backing vocals on closer “The Supermen” are reminiscent of Led Zep’s “Immigrant Song.” “The Width of a Circle” doesn’t sustain that sound for its 7-minute run-time, and neither does the album at large: hence why the shift from folk musician to heavy rockstar isn’t as pronounced as others who came before Bowie: “Black Country Rock” has some searing guitar transitions but otherwise plays like a T. Rex boogie; “The Man Who Sold the World” has a weirdly whimsical drum sound and could have used something with more snap. (Put me in the camp of people who think that Cobain did it better on MTV Live and Unplugged even though Cobain pops his 'p’s on that one so much.)

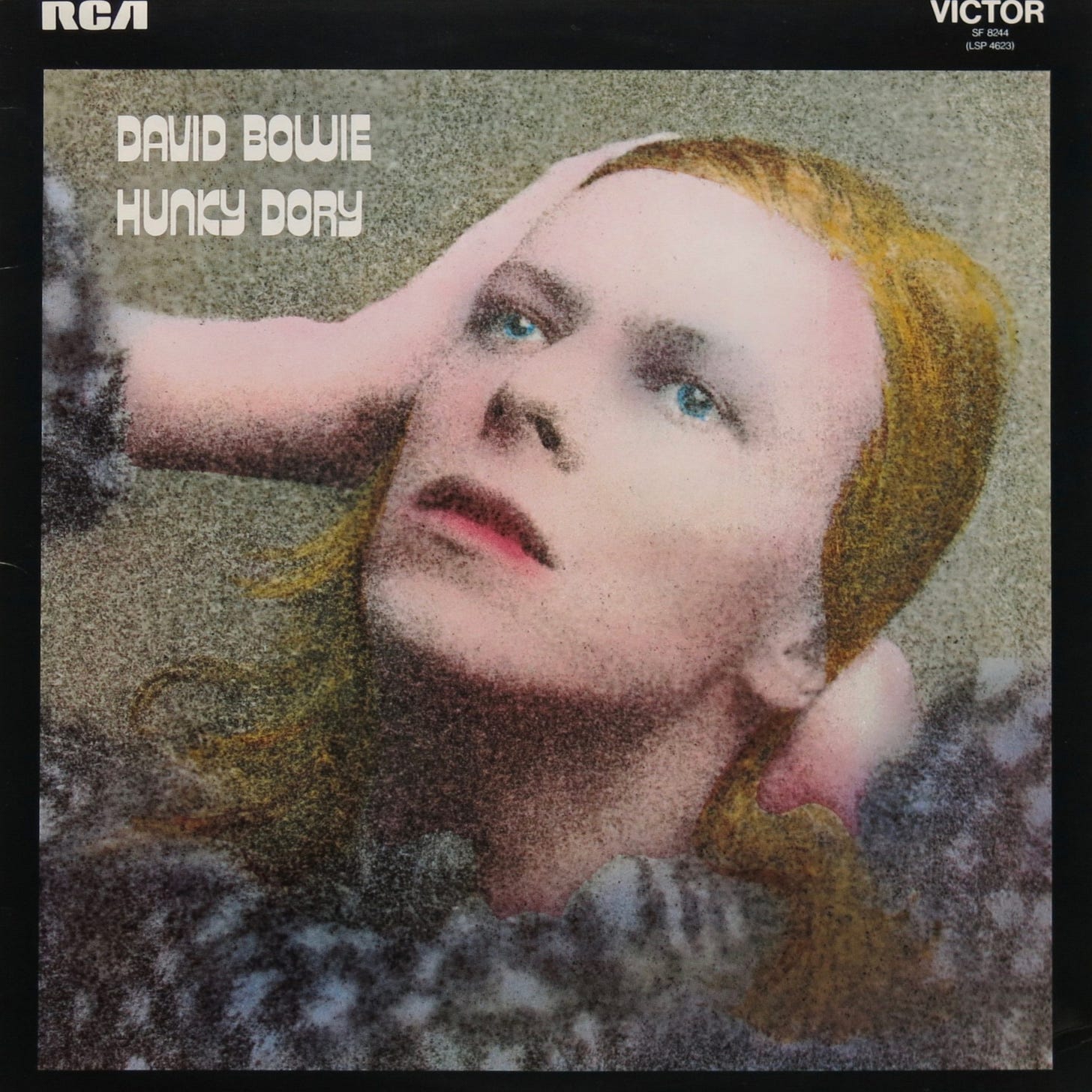

Hunky Dory is interesting because it’s the rare record where Bowie is earnest as he writes songs for Andy Warhol and Bob Dylan and dedicates “Kooks” for his son Duncan Jones. The two singles—should-have-been-a-hit “Changes” and would-be-a-hit-later “Life on Mars?”—dwarf everything else, and beyond those, I’m fond of the cheeky sentiment on “Oh! You Pretty Things” (“You gotta make way for the homo *wink* superior”), and the acoustic guitar of “Andy Warhol,” taking Velvet Underground chords to tribute the person who was partly responsible for that band in the first place. And “Quicksand” has a very beautiful string arrangement coming in for the choruses, and because of that, has a sweep to it that’ll be explored more fully on the next album. But too often, the choruses are disconnected from the verses, as on “Kooks” and “Oh! You Pretty Things,” while “Eight Line Poem” is pure filler. Altogether, I’d much rather listen to Lou Reed’s Transformer (which Bowie produces) or Elton John’s early-70s records, albums that felt like an early-70s ‘movement’ where rock musicians all put on ties to prove they could grow up.

Which brings us to The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (hitherto referred to as Ziggy Stardust but the full fantastical name is part of the charm, which the aforementioned Bolan basically took wholesale a few years later on Zinc Alloy And The Hidden Riders Of Tomorrow). This album plays like an amalgam of all the different British Invasion bands that Bowie loved, sporting a wild concept akin to the Who’s Tommy except crucially in the tighter rock model of only 11 songs: no interludes, no overtures, no short skits, but a story told through viable hit after viable hit after viable hit! Whereas Marc Bolan was a folk musician turned into a glam rock star, David Bowie’s Kinks influence tempered his rock vision with a folksy sensibility, which was more notable on Hunky Dory, but still shines through on this album. Actually, Ziggy Stardust rocks way less than one would think for an album that you see consistently ranking among the top 100 rock albums of all time: “It Ain’t Easy,” “Star,” “Hang on to Yourself” and “Suffragette City” are just about half of the album, and of those, only the latter-most scorches; the rest of the album rocks in a fairly midtempo way at most.

Worth stating great as this album is, it is emblematic of Bowie’s output that entire decade, which is to say that the quality was not a constant plateau: “Star” and “Hang on to Yourself” are the filler chugging rockers that people lambast certain songs on Lou Reed’s Transformer for, and “Ain’t It Easy” should have been cut.

But some of the rest of these songs are classics that are unique to Bowie in the sense that no one else could have pulled them off. “Five Years” sets the stage of an imminent apocalypse from the opening dry and ominous drum beat, and it’s Bowie’s vocal performance that sells it, especially when he becomes a one-man chorus from a Greek tragedy at the end. (Just a note: “Five Years” has a similar sentiment as Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s “The Dead Flag Blues” beyond the apocalypse: “I kiss you, you're beautiful / I want you to walk” versus “Kiss me, you’re beautiful / These are truly the last days.”) My favourite line is the one about milkshakes “cold and long”: a simple pedestrian detail that would be missing in anyone else’s vision of imminent doom. “Starman” re-jigs a trick from one of the most popular songs in pop history—the vocal octave jump of “Over the Rainbow”—and makes it rock history. “Suffragette City” forces itself into the proto-punk canon with pure speed, and no one can resist the complete stop for the delivery of “ahhhhHHHHHWHAM BAM THANK YOU MA’AM!” “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide” is an all-timer favourite Bowie song for me ending this sorta crescendo-ing album with an incredibly touching crescendo. The starting lines “Time takes a cigarette, puts it in your mouth / You pull on your finger, then another finger, then your cigarette”—is as wonderful a description of the passage of time in so few words and a single image. These songs played a huge role in convincing young me that rock music was much more than just rock music. You could say this album opened strange doors for me that we’d never close again.

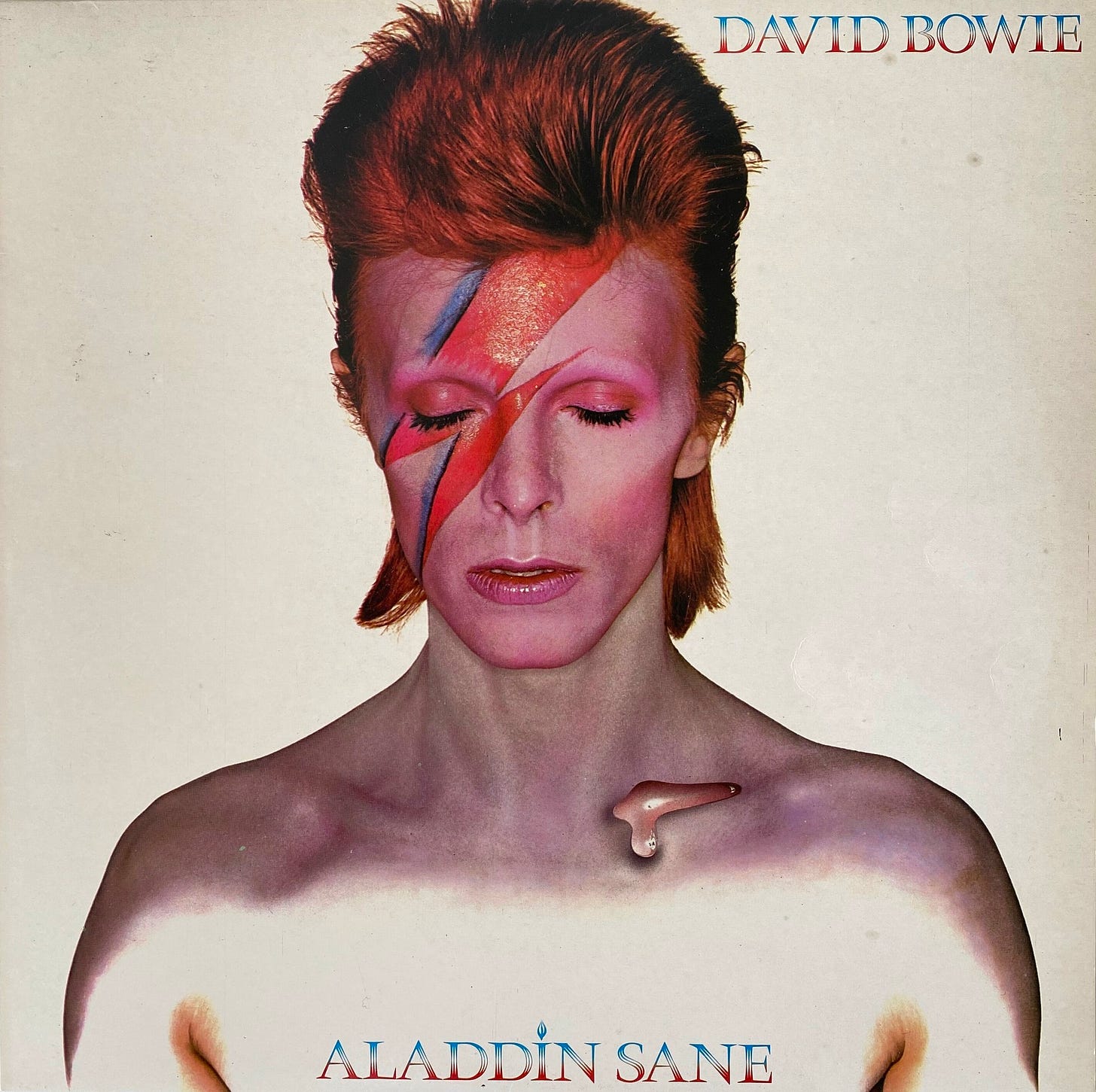

Whereas Ziggy Stardust made him a critical darling, Aladdin Sane (‘a lad insane’) pushed him to bonafide stardom: “Jean Genie” became his highest-charting hit at the time at #2 on the UK charts, which is crazy when you think about it since it’s a far more basic single than “Changes” or “Life on Mars?” or “Starman.” (Somebody clued in, finally: “Life on Mars?” was finally released as a single in 1973, two years after it was available, and even then, it didn’t chart as high as “Jean Genie,” peaking at #3.) To its detriment, Aladdin Sane ditches the folk component—that Kinks sound—replacing acoustic guitars for electric ones but not really upping the tempo enough for the guitars to truly sear.

Written on the road while touring Ziggy Stardust in America, it is a thoroughly American metropolitan album (“Watch That Man” = New York; “Cracked Actor” = Los Angeles) that only returns to London for its closer “Lady Grinning Soul” (which is the most acoustic cut). Like his albums before it, there’s some filler: Bowie’s cover of “Let’s Spend the Night Together” is awful while “The Prettiest Star” is forgettable. What it does have is one of my favourite piano solos on a rock album ever in Mike Garson’s free jazz detour on “Aladdin Sane (1913-1938-197?),” an early indicator in how interested Bowie was in other musics; notably, Garson showed up with more ‘rock-appropriate’ solos that Bowie continually rejected until Garson dropped this one.

Pin-Ups is a toss-off, a collection of covers that ranks as David Bowie’s worst record at this point, curiously released around the same time as the Band’s Moondog Martinee (also a covers collection; a similar toss-off). Anyone paying attention to Bowie so far won’t be surprised by the song selection: the Kinks, the Who, the Pretty Things, the Yardbirds. The problem is that Bowie doesn’t do enough with the source material: he doesn’t even sound invested in them. Certainly, he isn’t interested in deconstructing any of them beyond slowing down the Who’s “I Can’t Explain.” More details like the saxophone texture—just a few notes—in the choruses of Them’s “Here Comes the Night” would have gone a long way to make this record worth it, and frankly a more interesting song selection too: no Stones, likely because Bowie just covered them, but no Beatles or Velvet Underground either. (Actually, he’d soon cover the Beatles and it turns out that that wouldn’t have made this record any better.)

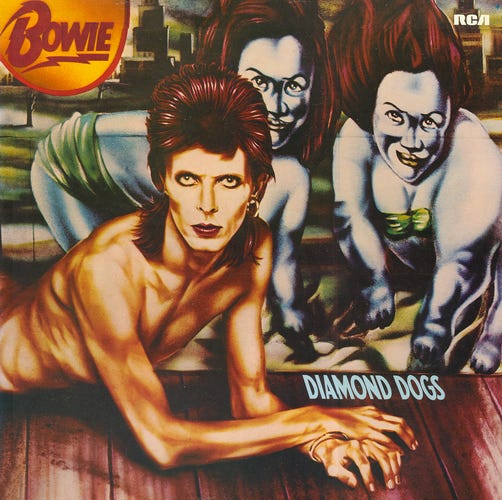

Ignoring Pin-Ups then, Diamond Dogs is the follow-up to Aladdin Sane: even more sleazy and decadent. By 1974, my interest in glam rock basically evaporates outside of a few songs by Sparks and Queen (two albums apiece), with the comparatively brain-dead entries from Bowie, Roxy Music and T. Rex and even that live Lou Reed one; none of whose albums hold a candle to their preceding ones (again, ignoring Pin-Ups). (Even the covers of these albums are so, so lame; especially that Roxy Music one.) Mick Ronson is desperately missed on Diamond Dogs, highlighting how much heavy-lifting he was doing on Aladdin Sane, and Bowie is left to riff on uninteresting chord progressions by himself, especially on the inexplicably long title track. “Rebel Rebel” is the new “Jean Genie”: loud and catchy and uninteresting. A few of the songs look ahead to Young Americans in their light funk/soul arrangements: Tony Visconti’s R&B soundtrack-ready string arrangement on “1984” (the second-best song here); vaguely funky filler closer “Chant of the Ever Circling Skeletal Family.” There’s a half-realized concept, inspired by George Orwell’s 1984 which further highlights the failure: “Five Years” set the scene to Ziggy Stardust with a only a loose beat and sobering vocals; "Future Legend” introduces Diamond Dogs with a skit.

Having taken glam rock to its glammy extreme, Bowie thankfully shifted on his next albums while Roxy Music and T. Rex stopped being good. Young Americans is pop soul through and through (and includes Luther Vandross among its backing vocals very early in his career), but not very good at that, alas. Bowie’s vocals could be very soulful, but he often took too many liberties while trying to achieve that hard-to-define thing that is ‘soul’ and ended up landing on the opposite side of the spectrum. Results, then, are predictably mixed. When there’s at least some groove in the rhythm, Bowie can skate by: “Fascination,” “Right” and especially “Fame” are all fine. By contrast, “Across the Universe” is unlistenable dreck in his hands. The title track is the best song here: the groove is spare but moves enough, letting the saxophone, those backing vocals and—most of all—Bowie himself ride it gloriously.

Because Bowie sings ‘transition’ on “TVC 15” as the hook, a lot of people have brought up a supposed Krautrock influence on Station to Station and argue that the album looks ahead to the “Berlin Trilogy” right around the corner. So let’s get this straight: there is no Krautrock influence here; there’s not a single beat that could be characterized as ‘Motorik’ and makes me wonder if people are just banking on the first song’s extended run-time for their own narratives. At only six songs, Station to Station features the least amount of songs than any other Bowie album, and so it particularly hurts when a song doesn’t work: the cover of Nina Simone’s “Wild is the Wind” is, well, after those bombed covers of the Stones and the Beatles and Pin-Ups in general, what did you expect? The funky cuts “Golden Years” and “Stay” are even funkier than those of Young Americans and highlights just how much bassist George Murray and drummer Dennis Davis are contributing here; likewise “Word on a Wing” (too long and a little corny) has much to thank for Springsteen piano man Roy Brittan, who also helps elevate “TVC 15.” “Golden Years” ranks among Bowie’s best: when I heard the news of Bowie’s passing, I immediately put on this song so I could hear the touching “Nothing's gonna touch you in these golden years.” ‘His least-good best album’ seems like a weird thing to say, but it also feels right so I’m going to say it.

Bowie worked hard in ‘72: he rescued Lou Reed and Mott Hoople and released Ziggy Stardust, but he outdid himself in ‘77 by releasing two great albums instead of one while also being responsible for producing Iggy Pop’s The Idiot and Lust for Life. Low is far more reliant on sound effects than actual songs, exemplified by the fact that Tony Visconti’s wife’s indelible wordless hook on “Sound and Vision” only happens once on the album’s first song that breaches the 3-minute mark. But what sound effects they are! “Speed of Life”’s squelchily crashing in and promptly taking off into this strange new future that turns out to be far grayer than the orange world promised by the cover; squealing guitar riff of “Breaking Glass”; the ‘tssssss’ sound on “Sound and Vision” that might be a treated cymbal but always makes me think of a drop of coffee splattering on the burner and evaporating instantly; Bowie’s own shronked-out saxophone on that same song that finally brings his touching vocal in; the understated ‘beep beep’’s that caps the main riff throughout “Always Crashing in the Same Car,” a cartoonish little sound effect that contrasts with the hook based on a real-life event where Bowie deliberately drove his car into his dealer’s car after being ripped off; the piano intro of “Be My Wife,” which plays like Nicky Hopkins on steroids (the session pianist who graced all those Rolling Stones records); the blazing harmonica of “A New Career in a New Town.” I love these all to death. The second half is worse, because Bowie isn’t as good with ambient texture as he is with pop song texture, and I really wish Bowie didn’t open his mouth at the end of “Weeping Wall” which otherwise makes me wonder if he heard Steve Reich’s “Drumming.” Meanwhile, “Subterraneans” slows down the sparkling synths from the previous songs but doesn’t do enough with the open space until Bowie starts playing the sax again.

In the same manner that there’s always someone who points out that the title song is incredibly tragic (“I can remember standing by the wall / And the guns shot above our heads / And we kissed as though nothing could fall”), I am personally obliged to smack anyone who types the title of “Heroes” without the quotation marks. There’s nothing heroic about this album. It’s even bleaker than Low, to its power: the dispensing of the songs in the first half feels less like separating two distinct halves and more like ‘now that that’s done with, here’s the real stuff, that cold shit.’ (Although not helping my read on the album is that it ends with a silly song in “The Secret Life of Arabia” which plays like a bonus track in this context.) “V-2 Schneider” is more touching than any of the tributes on Hunky Dory by being, you know, actually great, the drums peaking in and out like a tweaked sample of “Metal on Metal” and easing us into the pool; “Sense of Doubt” shifts between huge-sounding ominous bass and synths that just barely remember what the sky looked like; the koto on “Moss Garden” is simply the most gorgeous texture out of any of these ambient songs (Low included). As for the first side, “Beauty and the Beast” is a darker, struttier take of Brian Eno’s Here Come the Warm Jets; the delivery of “You will be like your dreammmmmms” in the dead-middle of “Joe the Lion” is unsettling and makes me wonder how many times David Byrne listened to it before recording Fear of Music; Bowie’s vocals in the climax of the title track might be his last great vocal performance, or simply his best-ever; the saxophone on “Sons of the Silent Age” just off-sets the corniness of the choruses. A tough call on which album is better: I actually prefer Low’s first half (even if “‘Heroes’” is a far greater achievement), but I vastly prefer “Heroes”' second side. Years ago, I would have said “Heroes” but now I lean towards Low.

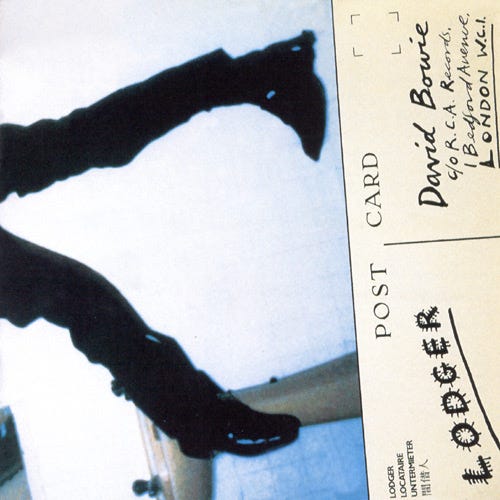

I liked Lodger when I first heard it, but every time I even think about it, it gets less and less interesting. For starters, this album continually gets lumped in with Low and “Heroes” as Bowie’s ‘Berlin Trilogy’ except this one doesn’t even sound like those two albums - it wasn’t even recorded anywhere near Berlin! If I could effectively rewrite music history, I’d get people to group Station to Station, Low and “Heroes” together as a trilogy but even then, I’d still say that Neil Young had the best trilogy of albums in the 1970s (in rock music).

The supposed charm about this album is how unpretentious it is, Bowie hitting a reset button right before the next decade and freeing himself from the obligations of listeners eager for another Low or “Heroes” that Lodger decidedly isn’t. Note the cover; the title. Sorta like Nashville Skyline the previous decade, although nowhere near as lovable. A few songs align themselves with spunky new wave—“D.J.” features David Bowie’s impression of other great David B. David Byrne (you read that right)—but Bowie doesn’t bring the songs and Visconti doesn’t bring the production. Compare these grooves with those of “Golden Years” or “Fashion,” and you’ll see what I mean: the drums on “Fantastic Voyage” sound feeble while “Boys Keep Swinging”’s choruses are begging for more pop. “Red Sails” is time better spent listening to early Eno or Roxy Music, with the “Fah-fah-fah” lifted straight out of Roxy Music’s “Re-Make/Re-Model” (“I could talk-talk-talk, talk myself to death”), and the last two songs are filler. “Repetition” depicts an abusive relationship but there’s nothing there otherwise while “Red Money” apes Iggy Pop’s masterful “Sister Midnight” (which Bowie produced) and isn’t as good, mostly because Iggy Pop imitated Bowie’s icy detachment perfectly, and Bowie couldn’t do Iggy doing Bowie as convincingly. The best songs are the most ‘exotic’ of the bunch right on the cusp of the ‘world music’ boom in “African Night Flight” and “Yassassin.”

See you next week for the rest of his discography. If you enjoyed reading this issue of Free City Rhymes, then I’d love it if you subscribed and shared!