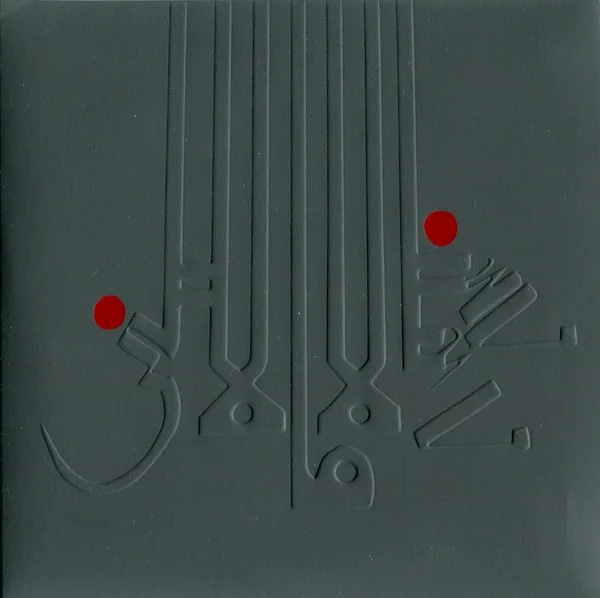

Digable Planets/Shabazz Palaces

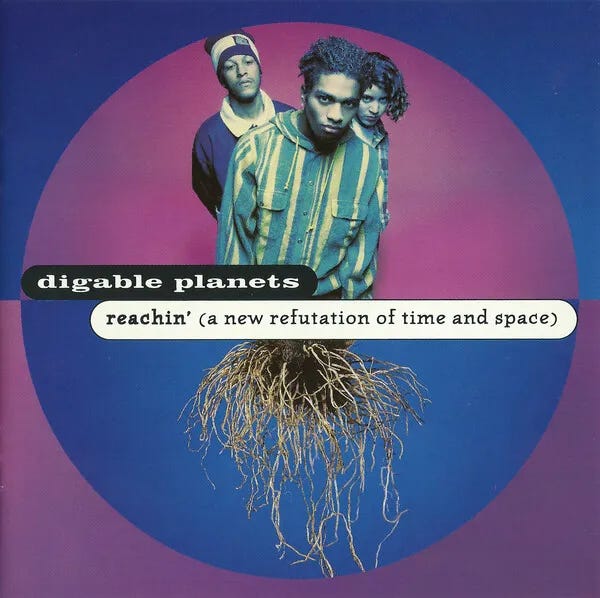

Reachin' (A New Refutation of Time and Space)

Digable Planets are a Brooklyn jazz rap group comprised of three rappers who donned themselves new aliases based on insects: Butterfly (Ishmael Butler), Ladybug (Mariana Vieira) and Doodlebug (Craig Irving). It’s a small detail but the fact that they chose insects suggested a down-to-earth-ness and the fact that their nicknames shared a theme suggested a togetherness which from the get-go gave them a friendliness and approachability more than just about any other hip-hop group — maybe even De La Soul.

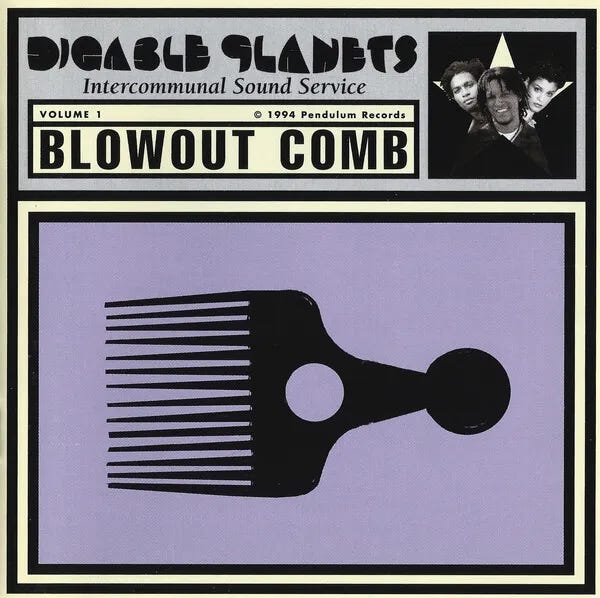

Paradoxical as it may seem, ultimately, it has helped Digable Planets’ legacy that Butterfly isn’t a great rapper. Not even on the same level as De La’s Posdnuos, and so not in the same conversation as Tribe’s Q-Tip. Because it forces the listener’s attention to the beats, which proved that jazz and hip-hop could—not just co-exist—but vibe together, a short-lived NYC afternoon daydream before acts like Mobb Deep started downplaying the jazz element if not outright removing it altogether. I don’t think anything sounds like Blowout Comb which blends in a lot of actual people playing actual instruments with some samples so that it doesn’t merely sound like rap using jazz samples like so much jazz rap, but rather actual jazz music that just so happens to feature rapping on it. Clearly Blue Note agrees with me, or else they wouldn’t have put out their compilation album Beyond the Specctrum: The Creamy Spy Chronicles in 2005.

Notably, there are a few examples of that prior to 1994, namely Tribe tapping Ron Carter for The Low End Theory and then De La Soul bringing in a jazz band for (alas, only) two cuts on underrated Buhloone Mindstate (a weird album for ‘93 but still third for De La), but Blowout Comb is more realized than either of those examples. And helping solidify Blowout Comb’s status as a special little darling is that Digable Planets pulled a Neutral Milk Hotel or Jean Sibelius and stopped making music right at their peak, citing disillusionment with the music industry among other reasons. (Blowout Comb predictably charted much worse than did Reachin’, which probably didn’t help.) Yeah, the axis of artists who hung up their cape at their peak: Sibelius, Mangum and Digable Planets, unless I’m forgetting someone obvious. Here’s the guide:

A scan on the WhoSampled page lists out samples from Art Blakey, Cannonball Adderley, Grant Green, Herbie Hancock, Herbie Mann and Sonny Rollins among a healthy selection of 70s’ R&B for good measure, demonstrating a genuine love for jazz early on even if they haven’t tapped any real players yet. If I’m ever reaching for a little groove straight to the ass, you know I’m going for the obvious one: “Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat),” which is their hookiest song (Tide used “Rebirth” to advertise how cool it is saving money using their detergent) and what usually ends up happening is the song will end and then the humid treatment applied to Adderley on the following “Last of the Spiddyocks” comes up right after and I end up playing the rest of the album in full. What I mean is, it’s impossible to isolate any of the songs from either of these two albums when they’re both such ‘music for the vibers,’ to quote another like-minded artist. The bass-lines they found for “Pacifics” and “Rebirth” are just so fucking good, they give me life. A few negatives: we all know how good the opening sequence of Herbie Hancock’s “Rain Dance” is (from his best fusion record Sextant; Head Hunters has more funk but less blood), and no matter how good the rest of “It’s Good to Be Here” is, I think it’s cheating to have that sample open your record and do nothing with it; “Appointment at the Fat Clinic” has that really unique percussion sound and a sample of “Rebirth”’s bass-line perks your ears up (the 0:56 mark), but when the drums thicken up, it make me long for the similar trick they’ll use on “The Art of Easing” since here, Doodlebug just shows up with a megaphone instead. Both Tribe and De La Soul had the better albums that year (there is no song here as good as “Steve Biko,” “Award Tour” or “I Am I Be” or maybe even “Eye Patch”), but this would be a happy third in the year that should be fondly remembered for jazz rap’s all-too-brief supremacy.

In the boring-ass Illmatic vs. Ready to Die debate of 1994, I quietly climb up on my treehouse so I can listen to Blowout Comb by myself. Not the better rap album, obviously. Again: Nas and Biggie are among the best rappers ever; Butterfly isn’t. Gun to my head, I remember even less words here than I do on Reachin' because they’re even less the focal point. The parts I remember are the instrumental noise, noise, noise, noise: the coronating horns of “The May 4th Movement” that anticipate a far more upbeat album than the one that comes, the little underwater guitar climb that ends that song; the sputtering electric guitar that sounds like a voice on “Black Ego” (it reminds me of that strange little osund on the Smashing Pumpkins’ “1979”); the catchy saxophone that introduces “Dog It”; the thick bass-line of “Jettin’”; the golden 60s’ psych sitar-as-hook on “The Art Of Easing,” those glorious horns on closer “For Corner” while the sweeter voice of Monica Payne tells us what we already knew, that these cats got the funk.

Samples are still used, but they’re sometimes so minor it’s unbelievable that they found stuff so obscure just to blend them in as additional sounds: the voice grunting “rapping black” throughout “Dog It” actually arrives from from 1971 which is insane to me, and a literal second of Rahsaan Roland Kirk album is scratched and looped in the conclusion of “Borough Check,” both extreme examples of ‘they didn’t need to do that but I’m so glad they did,’ and notably both of these examples celebrate blackness (the Kirk sample comes from his album titled Blacknuss, a minor Kirk album) to the point that I wonder how many times Kendrick Lamar spun this record before making To Pimp a Butterfly. It’s because of the samples that “9th Wonder (Blackitolism)” was probably chosen as the album’s lead single because it’s also the album’s least rewarding track and maybe even the worst thing to their name: catchy elements from Grandmaster Flash and Ohio Players that are trying to declare themselves over the song’s flatulent synth.

It feels kinda wrong to claim Blowout Comb as one of the best jazz albums from the 1990s—the same wrongness I get when I think the same about John Zorn’s Naked City—but it’s right to be wrong in these cases.

That’s basically it for Digable Planets. There was one live album recorded during their latest reunion that contains predictably less airy, less special renditions of songs, mostly from Blowout Comb.

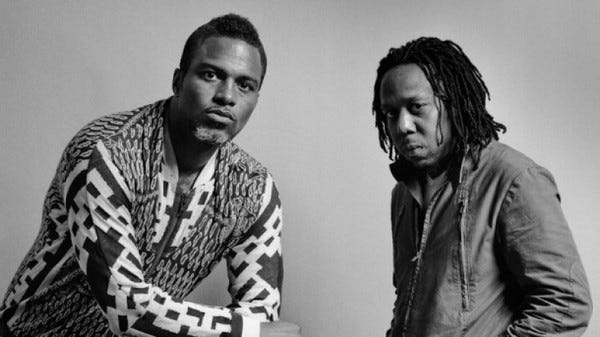

Then there’s Shabazz Palaces. 15 years after Blowout Comb, Butler would remake himself into Palaceer Lazaro and link up with multi-instrumentalist Tendai ‘Baba’ Maraire and form this new abstract group. They throw the occasional bone for Digable Planets fans that might have carried over after all those years—the wafty saxophone that peaks in and out of “Endeavors for Never”; the bass-line that essentially is the entirety of “Soundview”—but ultimately the jazz (barely any) serves only to highlight how different these beats are from what anyone else is making, part of the early-2010s push in underground hip-hop that seemed to be rebelling against how fangless mainstream rap had become by deconstructing what exactly hip-hop was in the first place.

If you asked me in 2012 who was more special, I would have said Shabazz Palaces. If you ask me in 2022, I would say Death Grips without hesitation - Death Grips just had more longevity, whereas Palaces felt more like a flash in the pan. Not that I listen to either much, mind you. One thing worth noting is that while I don’t think of the Digable Planets albums as dark (even considering the more downcast and mellowed out Blowout Comb), that’s certainly the vibe I get from Shabazz Palaces, and the transition from Butler to Lazaro is basically 90s’ optimism replaced by 2010s’ cynicism. (Or am I projecting too much?)

The ‘banding togetherness’ that was present in the blend of voices and Marxist lyrics and the aforementioned nicknames of Digable Planets have been replaced by, well, honestly, nothing. There is one very telling moment on the opening song of their debut album: “These robots grant us internets / Program racist sequences,” reminiscent of Andre 3000’s chilling verse on “Synthesizer” in its anxiety of soon-to-come technology. And yet, because the words mean so little to Lazaro now, he follows it up with “Don’t compare my beat with his / He ain’t up off these streets.” Somehow, we’ve gone from predicting racist predictive algorithms in 2011 to taking shots at a faceless rapper. Lazaro’s response to an interview with NPR about his lyrics was very telling: “Well, I feel like the words and the music and the melodies and the rhythms is like, they happen to me more so than I generate them. Those lines come to me and I say them, and I listen to them later and don't remember where they came from.” It shows, and not in same way as other rappers who might also improvise words but create some sort of weird dream/nightmare sequence with them.

In 2009 there were two EPs which, had they been combined into an album, would’ve still made a strong debut and I’m not sure why they didn’t go ahead and do that when so much hip-hop conversation revolves around the consumption of albums and not EPs. “Blastit” is the major highlight of either, featuring what sounds like vibraphones and toy train whistles and is ultimately whimsical and even cute in a way that none of their other songs are, and I wonder if one of Kanye West’s advisors heard it and brought it to the man because “In the starlight underneath the moonlight / Street lights, club lights especially candlelights” makes me think of a similar ‘lights-lights-lights’ run in “All of the Lights.” And “Chuch” has an addicting vocal that’s looped back and forth into sounding like a chant over the dense On the Corner-ish city funk of the beat; it gets to claim the title of “Best Song Named ‘Chuch’” for all of two years before Main Attrakionz usurped them with one of the five or so cloud rap songs that had a genuine beauty to its beat. But there’s the feeling that they’re throwing ideas around and not entirely sure what might work and what won’t, so you’ll see stuff like exciting African drums come in for only 2-4 measures near the end of “Gunbeat Falls” and then disappear forever as the main beat returns, or the underused saxophone ushering the climax that’s honestly less exciting than said sax on “100 Sph.” “Spechol-Analog” is badly produced and badly performed (by some guy named Dougie) and “My Mac Yawns” is just so boring. And even still, I’m tempted to say this might’ve been their best album.

Black Up was interestingly released on indie label Sub Pop which was very weird to see, although not as weird as 4AD releasing SpaceGhostPurrp the following year which was truly bizarre. 4AD, home to Cocteau Twins, Pixies, Red House Painters and…“Suck a Dick 2012.” There are remnants of Palaceer Lazaro’s past life, namely in the vibraphone bridge of “An echo from the hosts that profess infinitum” and then the aforementioned saxophones in “Endeavors for Never,” the two major highlights; the former has an addicting twisted sample that sounds akin to that of Death Grips’ “Birds” (play them back-to-back and let me know if you feel me). “Recollection of the wraith” has a soul sample that wouldn’t have sounded out of place in a RZA production, so Maraire distorts it partway through, achieving an uncanniness that makes me think of OPN’s treatment of voices on “Chrome Country” although the beat is annoyingly empty whenever that sample isn’t happening. Similarly, the following “The King’s new clothes were made by his own hands” also reminds me of Lopatin in how the very small loop keeps feeling like it’s skipping, ultimately giving the short song some unlikely momentum. “Yeah You”’s two-note bass creates a monolithic pummel over the interesting drum onslaught which mixes thick drum programming, guns reloading and what sounds like a cash register opening. Listen close: you’ll never hear drums sounding that good on a Shabazz Palaces song again.

Lese Majesty is less songful, 18 tracks compared to Black Up’s concise 10, most of them short, arranged into 7 suites because everybody liked Kid Cudi’s Man on the Moon II: The Legend of Mr. Rager so much. With no songs as great as most of the ones on Black Up, it’s easy to see why people just passed this up. I think suite 2 loses the plot as soon as it starts, and that “Noetic Noiromantics” is awkward as just about every hip-hop love song in existence (ignore the awful attempt at an internal rhyme in “I never thought that I would find else somebody / Who never thought that there was fine someone as me,” the line doesn’t even read right). I think that the fast-paced, heavier-beat songs in the second half are not nearly as rewarding as the spacey ambient-drift songs like “Dawn in Luxor” and “Forerunner Foray” that I get so much out of. “#CAKE” might be a self-aware parody, but that don’t make it good; “MindGlitch Keytar TM Theme” (great title) sounds surprisingly amateurish, and frankly the drum programming starting here on out leaves a lot to be desired.

Lese Majesty still plays like a masterpiece compared to what came next, which was essentially a repeat of the Smashing Pumpkins’ Machina albums in spirit and quality straight down to Lazaro now becoming ‘Quazars’ (Corgan also loved deliberate misspellings) and the evocation of ‘Jealous Machines.’ Two albums released simultaneously, neither invite listens from front to end and so invite the most devoted to assemble a far stronger playlist out of both despite the fact that there’s ostensibly a concept somewhere in there (“I'm from the United States of Amurderca myself / Nah, nah, we post-language, baby, we talk with guns, man”). Highlights are spread out evenly between the two albums, notably the housey thump of “Gorgeous Sleeper Cell,” the 50s strings of “Shine a Light” (their most normal song ever), the electro-rave of “Moon Whip Quäz.” And by the same token, a lot of bullshit to sort through as well, mostly through barely-developed beats which sometimes are even instrumentals (“When Cats Claw,” “Dèesse Du Sang,” “Atlaantis,” “Love in the Time of Kanye”); Born on a Gangster Star opener has an assist from Thundercat who’s invited in to do absolutely nothing but I think made the introductions so that Shabazz Palaces would appear on Flying Lotus’ album Flamagra in 2019.

I don’t think the issue with these Quazars albums or 2020’s The Don of Diamond Dreams is that what was avant-garde in 2011 would naturally become passé as more and more experimental acts started up (which is also true). Maraire’s beats (forget the more diverse array of sounds, just the literal drum beats) never sounded as fertile as they did on their EPs/Black Up, and Lazaro wouldn’t try as hard on the mic either (I’d peg his best performance as “Gunbeat Falls” back in 2009). The Don of Diamond Dreams is their worst album yet despite the fact that they’re doing the Digable Planets thing of blending in real performers (zonked out guitar solos; some saxes near the end) since the beats that are far too languid on songs that are already too long.

Not to end on a bummer note, but it’s cosmically cruel that we only received two Digable Planets compared to five Shabazz Palaces albums when it should have been the other way around.