Given how inescapable Michael Jackson’s hits were growing up, I had championed Janet Jackson early on as the Jackson family underdog, especially when Rolling Stone turned me onto Rhythm Nation 1814, the best pop and best R&B album of its year. (I stress that the term ‘underdog’ is relative. Janet Jackson was huge, and broke many a record.) That was when I was 20 years old.

Almost a decade before that, Janet Jackson was exiled from the public because of the widely-televised Super Bowl half-time scandal in 2004. Her new singles and music videos from her upcoming album were blacklisted off the radio and television. Her 2004 album’s lead single peaked at #45, whereas the lead commercial singles of her previous four albums all went to #1, and the follow-up single didn’t chart at all. I’m proud to say that 12-year old me thought the outrage was overblown, but that’s because the words “nipple slip” and “Super Bowl” have never registered to me as anything more than just words. The wardrobe malfunction inspired Jawed Karim to found YouTube when he had difficulty finding clips of it online, so we can indirectly thank Justin Timberlake for giving us CinemaSins.

But at some point when I became 30, the critical dialogue around Janet Jackson began to pendulum shift the other way as part of the cultural shift of poptimism. Perhaps most notably, in their revamped list of best albums from the 1980s, Pitchfork placed the two main Janet Jackson albums from that decade ahead of any album by Hüsker Dü, Pixies, Minutemen, or U2. If ever there was a claim that Janet Jackson was an underdog, it’s hard to justify now.

More than her brother, Janet Jackson often gets compared to Madonna. Both queens of pop that started in the early 1980s who released their sexual albums (Erotica vs. Janet) and then their mature albums (Ray of Light vs. The Velvet Rope) around the same time. I don’t think there’s any comparison. Madonna was far more adventurous, musically; ultimately, Janet Jackson doesn’t have enough songs like “Together Again” to come close on that front, and it’s important to note that her reinventions from album to album from 1986-1993 were less musical, but rather reinventions of the self: Control as familial independence, Rhythm Nation as political independence, and then Janet as sexual independence. Moreover, Madonna was also willing to bend, stretch, and even break her voice in a way that Janet Jackson physically couldn’t, and that range and power gave way to stronger melodies. By contrast, Janet is a thin singer, and she started mining a more sensual territory. Her songs do not have strong melodies. In fact, I barely think of songs like “Miss You Much,” “That’s the Way Love Goes” or “All For You”—all #1 hits—as having actual distinct melodies, but catchy, simplistic tunes — even if I like all three of them.

At best, Janet’s best songs are exploration of quieter, more textural side of R&B, which has trickled down as an influence into the breathier modern strain of R&B from SZA to Solange (who really took Janet’s short skits to heart) to FKA twigs. And some of her work in the 90s can even be classified neo-soul, especially when she started working with hip-hop artists, something that I think she should have done more of. On the flip side, being less loud has also allowed her music to age better than Madonna’s (it helps that she was a slow worker), and ignoring her first two albums where she had no creative control anyway, Janet released only one bad album, Discipline, whereas Madonna has released many embarrassing albums after 1998.

Forced into the world of music by her father, Joseph Jackson, Janet released two albums with him at the helm, neither good, and neither even trying to establish the singer as an actual human being with their own thoughts, feelings, and even voice but rather just another cog in the disco machine. Janet Jackson is the lesser of the two, and I can only imagine her half-hearted “hoo hoo” near the end of lead single “Young Love” was forcibly deployed as her domineering father loomed over her during recording. Second album Dream Street charted significantly worse, but what I think what happened was the debut was riding on her family name, but people realized that she wasn’t as good as her brother and didn’t bother with her sophomore. But the album is only helped by the presence of Giorgio Moroder, who gives her disco beats that are far less faceless than the ones on her debut even if he’s phoning it in.

Control makes its mission statement plain in the title and opening lines, “This is a story about control / My control / Control of what I say / Control of what I do / And this time, I'm gonna do it my way,” as she severs ties with her father and starts a new relationship with production team (Jimmy) Jam & (Tammy) Lewis, a production team coming off of being fired from Prince and on the lookout for someone new to work with. The album is a good one, but I think the narrative—of a young woman taking control for herself—has made it overrated overtime. Being associated with Prince, Jam & Lewis’ drum beats often consume the rest of the song. “Gimme a beat!” she demands on “Nasty,” and then Jam & Lewis provide one that feels like digitally-manipulated breaths. But at the same time, the first half feel beholden to their beats, peaking early and then trying to sustain interest for another five minutes. “What Have You Done For Me Lately” is the worst offender because there’s barely a song there, just a skit and then the drum drop, and the last few minutes just spin its wheels. The ballads are less rhythmically interesting, but the melodies shine more there, and I think Maxwell took closer “Funny How Times Flies (When You’re Having Fun)” and made a whole album of it with Embryo, which is namely R&B that you can practically swim in, except I think Janet did it better 12 years before him.

The headline that Rhythm Nation 1814 is a deeply political album isn’t necessarily wrong, but it also doesn’t mention just how bone-headed the actual politics are. I think it’s incredibly telling that she says the artist that inspired the album was U2. But the album slams with such intensity that it’s hard to really be bothered about the words (quoth Xgau, “her music is the message.”) The album isn’t perfect: putting all of the ballads in the album’s last stretch makes the last 15 minutes feel like 30, and only “Lonely”—rescued by Oneohtrix Point Never as Chuck Person—matters most of the three. “Black Cat” feels like a misunderstanding on Janet Jackson’s part (it’s the only song on the album written entirely by her), as if she listened to her older brother’s “Beat It” and “Dirty Diana” and wrongly attributed the successes to either to the over-the-top guitar work; it’s a fun song that I don’t mind listening to five times a lifetime and not once more than that. And even besides that, Jam & Lewis’ work on “State of the World” sounds too close to “Rhythm Nation,” and the second verse is some Bon Jovi shit; “The Knowledge”’s breakdown is just begging for some additional voices to give it some actual call-response power to be the modernized take of Martha & the Vandellas it wants to be. The two best songs are “Rhythm Nation” and “Escapade.” The former’s introduction—industrial-grade drums, a call-back to “Nasty,” a little count-down, and then Sly & the Family Stone’s funk blended up into something sharper—must surely rank among the greatest pop song introductions of all time. Meanwhile, “Escapade” opens with a sequencer line that makes you think it’s going to be a ballad — nope! But as opposed to the other tracks here, the groove is relatively simple which gives space for the addicting mini-hook ad-lib of “LET’S GO!” or the chromatic climb of a melody in the way the title word is sung in the chorus, her vocals digitized in a way that it looks ahead to the autotune era. It’s one of the very few “let’s go to the mall”-type hits of the 1980s that makes me want to actually go to the mall instead of filling me with absolute dread.

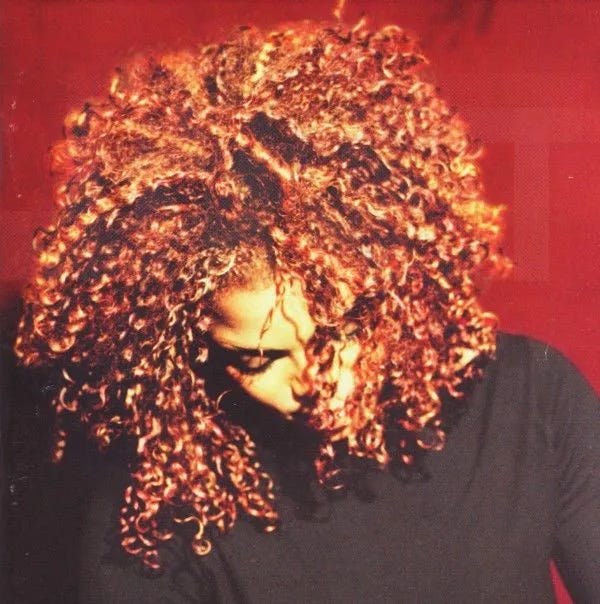

Janet does the Marvin Gaye thing of following up a deeply political album with a deeply sexual one instead; the album cover is famously from her topless Rolling Stone cover, making goods on her promise of “Let’s Wait Awhile” seven years prior. It’s also her worst album from her run from 1986-1998. Her run-times are now 75 minutes, burying what few good songs there are under the rubble of useless skits and filler. Not helping is that the good songs are all in the first half, from #1 hit “That’s the Way Love Goes” and top 5 follow-up single “If,” which feels like an R&B song using the throttle of a rap-rock beat; note the brief strings at the 3:00 minute mark. Don’t skip out on “Funky Big Band,” perhaps her deepest-deep cut; though the funk is very early-90s and the horns are unfortunately squelchy and not at all like a big band, Janet floats well over it. But the album is also all over the place, stylistically, and not in an artistic-eclectic way because the detours don’t amount to much: cheesy and over-sexual Eurodance (“Throb”), half-hearted take on alternative rock via a cover of late-60s forgotten Stax singer Johnny Daye (“What’ll I Do for Satisfaction”). As for “Any Time, Any Place,” I think it’s one of those cases where a song that sampled it—in this case, Kendrick Lamar on “Poetic Justice”—has rendered the original useless to me since the new song took the best part, the texture, and saved me 7 minutes.

At some point when I stopped paying attention, The Velvet Rope has been claimed by some to be her best album when it’s clearly not — it’s very similar to Madonna’s Ray of Light (notably from the same year) being heralded as her best even though it doesn’t hold a candle to her early, secretly far more sophisticated records. Again, 75 minutes, with every other track a useless interlude, and many of its songs are misfires. “Got ‘Til It’s Gone” sounds like J Dilla with Q-Tip supplying a verse and using a prominent use of Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi,” but to anyone who likes the song, I ask, what’s your favourite part involving Janet herself? Something similar happens on other songs here like the title track and “Empty”: the singer gets consumed by the song in a way that didn’t happen to her thin voice even over the industrial slammers of Rhythm Nation 1814. The title track has the cool aspect of sampling Mike Oldfield’s “Tubular Bells,” but the song sounds like bad video game battle music (/late-90s at the mall) even before violinist-turned-Olympic skier Vanessa Mae comes in with her proggish scrapping violin. (That being said, most of Janet Jackson’s contemporaries wouldn't have taken a chance on that violin.) “Rope Burn” sounds exactly like what DJ Quik brought for Tony! Toni! Toné!’s House of Music but worse. “What About” takes early-90s’ obsession with hard-soft dynamics to clang together hopelessly from what feels like two different songs. “Free Xone” sounds like a re-jigged “Rhythm Nation” but that bass sound at the 1:15 mark is so gross sounding. “Tonight’s the Night”—a Rod Steward cover, not a Neil Young cover alas—feels like Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Want to Have Fun”: a song where it’s easier to take these lyrics from a woman instead of a man (“Don’t say a word my virgin child / Just let your inhibitions run wild”; “C’mon, angel, my hearts on fire / Don't deny your man’s desire”), but in this case, hard to swallow regardless.

In this context, glorious afternoon thumper and centerpiece “Together Again” shines bright. That song always reminds me of Toronto pride, even though I don’t think I’ve ever consciously heard it there. Many have written about the LGBT theme throughout the album (even “Together Again” was originally conceived because her friend passed away from AIDS), but I think it’s sub-sub-subtext that’s lame by 90s standards and doesn’t deserve to be dwelled on. The opening verse of “Free Xone” goes like this, “He was on the airplane / Sitting next to this guy / Said he wasn’t too shy / And he seemed real nice / Until he found out he was gay / That’s so not mellow.” Gee, thanks. That homophobe? Not mellow!

A lot of people lose attention after The Velvet Rope. Don’t be one of these people. All For You—referenced extremely clumsily on a recent Taylor Swift song—might have her flat-out worse single yet on “Son of a Gun,” but the title track and “Someone to Call My Lover” are some of her best singles. The latter interpolates the melody of Erik Satie’s “Gymnopédie No. 1,” recasting the deeply haunting melody into one that’s fun and optimistic. 2004’s Damita Jo was buried because of the Super Bowl controversy, which is a shame because Jam & Lewis taps outside production help, which includes a young Kanye West on his ascent for three beats. For the Kanye beats, “Strawberry Bounce” uses a sample of Jay-Z going “bounce” as the hook, and the song plays itself out really quickly, but “My Baby” and “I Want You” are both tremendous work from Kanye thanks to acoustic guitar (name a better duo than early Kanye and acoustic guitar) and drumming respectively. But it’s not just of interest for Kanye fans to see his early work: “All Nite (Don’t Stop)” has a funky showstopper beat that Jam & Lewis probably wished was given to a non-blacklisted singer who could have turned it into a hit (it didn’t chart at all).

Janet brought in her newest flame to produce half of her next album, 20 Y.O., notable R&B producer Jermaine Dupri (/s), which ultimately proved how much she needed Jam & Lewis. So no surprise that she bottomed out when she decided to not work with them at all for her next one, embracing the late-2000s maximalist pop trends on Discipline. The first proper song goes “Cause my swag is serious / Something heavy like a first-day period” and choruses of “my Asian persuasion” (firing up ancestry.com to see if Janet is part-Asian), and the album does not pull up from there.

So when she released Unbreakable seven years later, it truly did feel like a comeback, showcasing a sweeter, surer, and yes, unbreakable side of her. What’s really interesting is that her voice—close to 50 years old at the time of recording—has aged to one that resembles her brother’s voice as it naturally deepened: the verses of “Broken Hearts Heal” (that builds towards a groove reminiscent of “Together Again”) and choruses of “Unbreakable” sounds very much like Michael Jackson is doing the singing. As always, there are too many songs: “Burnitup!” is pure radio fodder, one of the very few uppers on an album that wants to be mellowed out for late night reflection, and I lose interest 2/3rds of the way through the album. But the title track has a melody in the chorus that might be her sharpest in decades, and I love the vibe of “No Sleeep” although I hop off when Janet Jackson says “Cole world” to announce the feature. (Strangely, the beat under J. Cole’s verse gives him absolutely nothing to work with, which I was going to blame Jam & Lewis for, but Cole himself is credited with co-production, so I blame him.)

It seems like every time Janet Jackson did an interview since Unbreakable, she teased a new upcoming album that has yet to see the light of day. If her twelfth studio album is as good as Unbreakable, then I’ll be a happy camper. And if it never manifests into anything at all, that’ll be okay too, because she’s long reclaimed her legacy from her public fall from grace.

Janet Jackson - C+ Dream Street - B- Control - B+ Rhythm Nation 1814 - A- Janet. - B+ The Velvet Rope - B+ All For You - B 20 Y.O. - B Discipline - C Unbreakable - B+