One way to think of the symphonic form is that its four movements represent a hypothesis, two experiments—one slow, one fast—and then a conclusion. In 1907, Finnish composer Jean Sibelius rejected that model as the only option. He merged the fast movement and the finale into one on his third symphony, prompting Russian Five curmudgeon Rimsky-Korsakov to ask, “Why don’t you do it the usual way; you will see that the audience can neither follow nor understand this.”

Sibelius responded by doing it again on his fifth symphony, and on March 2, 1924—101 years ago today—he fully deconstructed the symphonic form by compressing it all into one single movement with his seventh and final symphony. The andante, scherzo and finale are all accounted for, but rather than present them in individual sections, Sibelius presents them as one single breathing organism to give the constant feeling of time warping around the symphony. (Which is why any renditions that go out of its way to try to parse the symphony out into four movements yields an immediate ‘no’ from me, so sorry, Sir Simon Rattle, I shan’t ever know if the seventh’s ending is truly like a scream as you say.)

I listen to Sibelius’ seventh a lot, partly because of its condensed length—22 minutes long in most recordings, whereas most of the symphonies post-Haydn tend to be around 40—but there’s a deep power within it that I don’t get anywhere else. Sibelius’ talents were how much he was able to draw out of relatively so little, and that’s proven out in the first three measures alone where there’s the soft rustle of a timpani, and then the strings perform the most basic of tasks, a C major scale, starting with a low A, and ending with a chord that doesn’t fit: an A-flat minor.

Consider the symphony a series of non-resolutions such that when Sibelius returns to C major for the ending, it is a resolution, yes, but the triumph is at once short, abrupt and muted. It feels like the destination has finally been reached, but at what cost?

One obvious cost was his life. The seventh symphony claimed Sibelius completely: the composer lived another 33 years and produced almost nothing of note beyond the incidental music for The Tempest (totally nice, based on the excerpts I’ve heard) and Tapiola (whose opening chord melody is among Sibelius’ best) shortly in the two years afterwards. He started an eighth symphony in 1924, and even seemed to be proud of its development at certain points, but continuously pushed back performances as it was not ready yet. It would never be: he lost his mind chasing perfection, unsatisfied with his inability to truly bind nature to paper and into sound. And so Sibelius is the rarest of musicians: one that completely stopped making music at their absolute peak.

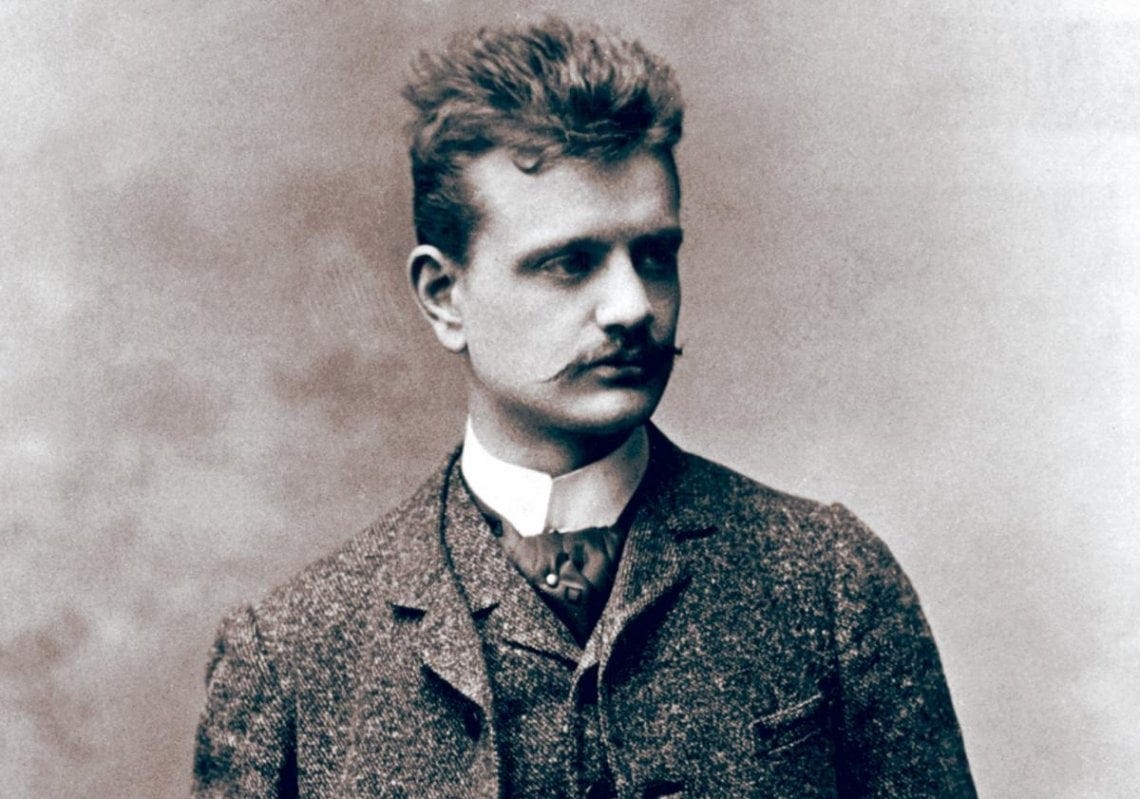

Born Johan Sibelius in 1865, later adopting the French version of his name, Jean, la crème of Sibelius’ body of work is contained within his symphonies and tone poems. If you’ve heard any Sibelius—aside from the fact that the seventh’s final chords are sampled in “Revolution #9”—I’d wager it’s Finlandia (1900) and Valse Triste (1904); the latter is his easily his most lyrical piece, composed as incidental music for his brother-in-law’s play. The former was written at a time when Finland was controlled by Russia, and it has a cool history of having silly alternate titles (i.e. Impromptu) so it could get through Russian censorship, and the tone poem represents Finland’s struggle for independence from Russia, which the country achieved in 1917. If you’ve seen the decidedly not-Finnish film Die Hard 2, you’ve heard the piece because Renny Harlin is Finnish and snuck it in.

Sibelius was not a piano composer, but he composed much of it in his spare time, by his own admission, so that his daughter could eat well. Glenn Gould liked some of his piano pieces, which for me is proof that they’re not good: Gould was a marvelous piano player, of course, but the things he liked and disliked had no rhyme or reason to them. That said, the first movement of Piano Sonata in F Major (1893) has a beautiful ring to its chords, and I particularly love the chords pictured below—clearly meant with strings in mind—that he should have capitalized more on to elevate this otherwise bog-standard sonata.

The power of his music written in the late-1890s was his ability to translate Finland’s nature into little musical snapshots. For example, The Swan of Tuonela (1895) has the beautiful plucked string textures that actually do sound like a chorus of swans mourning Lemminkäinen’s death. The soloist’s string melody on the first movement Violin Concerto in D Major (1905) backed by the subtle flutter from the rest of the orchestra is the melancholy-cum-purity of Finland in winter. That concerto is one of his best works that is neither a symphony nor a tone poem, and I’d say it trumps Tchaikovsky’s. (I’ll always associate the two together as some of eastern Europe’s most notable nationalist composers, and I find myself pairing off compositions in my head like Finlandia vs. 1812 Overture or the violin concerti.)

The longer tone poems tend to be symphonies in miniature: by which I mean, they’re clearly episodic (divided into parts). En Saga (1892) was the earliest, written at fellow Finnish composer Robert Kajanus’ suggestion that Sibelius write a tone poem with that would appeal to a wider audience. Sibelius complied with a tone poem with no specific programme; translating to “A Fairy Tale,” En Saga asks listeners to make up their own, though for Sibelius, it was something deeply personal: “I had recently undergone several painful experiences, and in no other work have I revealed myself so completely.” The rhythmic first main theme—around 5 minutes into the 20-minute piece—is heroic and yet still mournful, and a success in Sibelius trying to balance those two modes without tipping the scales in either direction, and the fifth and final section is a melodic, ambient drift led by a solo clarinet.

The Wood Nymph (1895) was sought to be lost, and only recorded in recent times; criticized for its highly episodic nature as it depicts the poem of the same name, Finnish conductor Osmo Vänskä is a fan of the piece, and was also the one who resurrected it from obscurity: it was thought to be lost before he recorded it almost a century after it was first written. The third section, led by a cello that’s meant to evoke the wood nymph, is Sibelius at his most erotic, but also a limitation for Sibelius because it’s not nearly erotic enough. Rather underrated among his tone poems is The Bard (1913) because it’s so slight by comparison—only 7 minutes—but the use of the harp to ‘reset’ the piece so that it never truly progresses is reminiscent of the glockenspiel in Symphony No. 4: unique textures that I wish he used more of elsewhere.

But it’s his symphonies that are his jewels, specifically the later ones. Consider Sibelius the anti-Mahler. Mahler was one of the last bastions of romanticism, his symphonies were modelled after Beethoven’s. In 1907, Sibelius and Mahler famously met and had a disagreement about the symphony, where Sibelius lamented the “severity of form,” to which Mahler replied, “No! ... The symphony must be like the world. It must be all-embracing.” Sibelius symphonies became more special when they stopped being “like the world” and “all-embracing,” getting shorter and shorter in length, whereas Mahler’s symphonies went the opposite direction.

Kullervo (1892) has been retroactively deemed a “choral symphony” given its form; Sibelius went back and forth about whether it was a symphonic poem and a symphony. If it is a choral symphony, then it is by far Sibelius’ longest. While living in Vienna, he attempted to reconnect with his Finnish roots by reading the Kalevala, a Finnish epic, and upon returning to Finland in 1891, sought out Finnish folk music which would have aligned him as the Finnish version Béla Bartók but he later claimed that folk was not an influence on his music. Kullervo is a tragic minor character in the Kalevala, abandoned by his family, Kullervo seeks out female companionship and unknowingly seduces his sister, then kills his foster family, and then himself. And so much of the appeal is that this Finnish composer is presenting a Finnish story, sung in the Finnish language, in a symphony modeled after the great Germans. The fourth movement flat out doesn’t work; set in C major with a very basic action-movie melody, it’s as if we’re cheering on Kullervo in his quest for parricide.

Symphony No. 1 (1899) has that remarkable intro of a solo clarinet painting the scene, sounding lost in the blizzard of wintry silence and uneasy tympani, evoking a picture of Finland in so few ‘words.’ And then the Andante ma non troppo is interrupted by the first movement’s major theme, a theme that comes in depicting “a cold, cold wind blowing from the sea” with such a forceful sweep that it’s always hard for me to not sit up when I hear it. (Both his and Elgar’s first symphonies are special in the sense that you can make a very educated guess of the nationalities of their composers from the music alone.)

Symphony No. 2 (1902) remains his most popular and the most performed of his symphonies which has never sat well with me. Osmo Vänskä writes that “The second symphony is connected with our nation’s fight for independence”—though worth stating is that Sibelius rejects this idea, so Vänskä continues—“but it is also about the struggle, crisis and turning-point in the life of an individual. This is what makes it so touching,” and that’s perhaps part of its appeal: that it’s Finlandia in symphonic form. The first movement’s melody is playful in the cat-and-mouse game near the end, and the fourth part is suitably heroic given what Vänskä said, but many of its loud parts—the third movement especially—are far too campy in their bombast and take you out of the Nordic gloom.

Symphony No. 3 (1907) is where Sibelius’ symphonies started getting juicy, no longer beholden to the 4-movement symphonic template that his first two followed, but like Tchaikovsky’s sixth which was an influence on Sibelius, I think that the toying of structures on both of these symphonies isn’t enough for me to commend them. The best movement is the third movement where he merges the traditional scherzo with the finale to explore the possibility of a more rhythmic climax and a less episodic symphony at the same time.

Symphony No. 4 (1911) was completed in the years directly following an operation to remove throat cancer, and so he lived in anxiety during that time of the possibility of cancer coming back, as well as the inability to indulge in his favourite vice, which was alcohol. As such, there’s lots of personal analysis that gets applied here, rationing that the fourth’s low melodic content—you can’t hum this one at all—and subversive has to do with Sibelius’ mental state. It makes for the only symphony of his that I would characterize as a slog, but you’re rewarded by the appearance of the bright and wonderful glockenspiel motif halfway through the fourth movement, like those brief glimpses of sunlight in dead winter.

Symphony No. 5 (1919) was written during the first World War, and like the third, Sibelius compresses two movements into one such that the fifth is a 3-movement symphony. It’s most famous for two components: the majestic horn motif inspired by the sound of swans, harkening back to The Swan of Tuonela, that pop fans might recognize for being incorporated into the melody of the Murmaids’ “Popsicles and Icicles” released at the height of baroque pop (even though, of course, Sibelius isn’t a baroque composer), and the silence-loaded finale:

This is Sibelius at possibly his most daring. The build-up leading into this coda are forte’s crescendoing into fortissimo’s crescendoing yet once more into forte fortissimo’s, and right as we’re wondering where Sibelius might go from there, he suspends us with a series of silences. A lesser symphonic composer—like Tchiakovsky—would have just kept the loud chords blaring over and over and increased the role of the timpani, but Sibelius was moving away from the traditional ideas of symphonic closure, which also applies to the fourth where he decidedly ends in mid-volume rather than loud or soft, which were more the norm.

Symphony No. 6 returns to the four-movement symphony, but its flow is marvelous: despite it being parsed out into different sections, it really feels like he was working towards compressing the symphony into a single organism as early as the sixth. The lilting instrumentation of the first movement brings to mind those stray snowflakes that seem to float in the air—Sibelius described the symphony “like the scent of the first snow”—which gives way to spring in the birdcall of the call-and-response of the chamber instruments. The second movement pulses in a way that reminds me of minimalism, whose movement looks ahead to the third movement which is Sibelius at his most whimsical, and the portion that I revisit most in isolation to feel some wind beneath my feet.

Symphony No. 7 is his best. Originally conceived as a symphonic fantasy, it was only published later as a full-fledged symphony, and though it’s only one movement, you can easily parse it out into sections. As such, it makes Sibelius’ experiments on his third and fifth symphonies look like mere stepping stones towards this total liberation. Were I to compile a list of ten classical compositions that I would take with me—to a desert island; for the rest of my life—then Sibelius’ Symphony No. 7 would make it in, easily. There’s a vastness to its scope despite its condensed shape and concise run-time (22 minutes).

Morton Feldman according to Alex Ross’ “Sibelius: Apparition From the Woods,” said in a lecture that, “The people who you think are radicals might really be conservatives [and] the people who you think are conservative might really be radical,” before humming Sibelius’ fifth symphony. It’s true that Sibelius could be prone to kitsch—but he was a nationalist composer operating still in the romantic era, so kitsch is part of the territory—but he was best when he was working with alcohol-fueled melancholy and subversive modernity. (I wrote all of this before I revisited that Alex Ross essay so I wouldn’t be redundant, but I found out that’s the case all the same, alas. Ross has an obvious love for research that allows him to play the role of critic and historian instead of one or the other, and he’s able to write about classical music while still analyzing the technicalities without it ever being dry.)

A lot of the reasons why classical music tends to get ignored by many music lovers don’t sit well with me because they don’t make any sense. Is it really that much more expensive to be a classical music fan and purchase tickets to your local symphony compared to going to a pop concerts? Are classical circles really all that snobbish compared to the fans of other genres? (A test: tell old-head classical listeners that your favourite composer is Hans Zimmer and let me know if their reaction is kinder than telling old-head rap listeners that your favourite rapper is Playboi Carti. Classical fans, at least in my experience, tend to just like the fact that other people are listening to classical.) But the one that really doesn’t sit well with me is that people dislike that classical compositions will have many, many different interpretations (recordings) making the canon harder to penetrate. Listening to more music? I thought that was part of the fun?

It is for me. For Sibelius, I’ve heard multiple different interpretations, and for the symphonies, I disagree with Sibelius’ assertion that Herbert von Karajan was “the one who best understands my music.” Karajan’s much too bold, which works for the tone poems, but his recording of Symphony No. 2 in 1962 is unable to tap into the melancholy that makes the triumph deserved. Most recently, Finnish conductor Santtu-Matias Rouvali has performed all seven symphonies with the Gothenburg Orchestra, capping off with the sixth and seventh that came out just last month, and he emphasizes the louder parts at the cost of the tender moments which don’t provide as much respite (still currently the best album of 2025 that I’ve heard, although that’s cheating). The Nordic gloom and moments of snowy tenderness came naturally to Osmo Vänskä, who is my go-to for all things Sibelius.

![{ \new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff \relative c { \key c \major \time 3/2 \clef bass \tempo "Adagio" r4\p^"Strings" a4-- b4-- c4-- d4--\< e4-- | f4-- g4-- a4-- b4-- \clef treble c4-- d4--\! | <es ces as>2\fz\>^"Wind, Horns" s16\! }

\new Staff \relative c { \key c \major \time 3/2 \clef bass << { s4 r8^"Bass" a,4--^\< b4-- c4-- d4-- e8--~ | e8\! \stemUp f4-- g4--^\> a4-- b4-- c4--\! d8--^\p| } \\ { \stemDown s8_"Timp." \grace { \stemDown g,16 [g16] } g4^> s8 s2 s2 | s2 s4_"Timp." s8 g8~ \trill\p\< g2\! | es'4. \trill\mf r8 s16 } >> } >> }

{ \new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff \relative c { \key c \major \time 3/2 \clef bass \tempo "Adagio" r4\p^"Strings" a4-- b4-- c4-- d4--\< e4-- | f4-- g4-- a4-- b4-- \clef treble c4-- d4--\! | <es ces as>2\fz\>^"Wind, Horns" s16\! }

\new Staff \relative c { \key c \major \time 3/2 \clef bass << { s4 r8^"Bass" a,4--^\< b4-- c4-- d4-- e8--~ | e8\! \stemUp f4-- g4--^\> a4-- b4-- c4--\! d8--^\p| } \\ { \stemDown s8_"Timp." \grace { \stemDown g,16 [g16] } g4^> s8 s2 s2 | s2 s4_"Timp." s8 g8~ \trill\p\< g2\! | es'4. \trill\mf r8 s16 } >> } >> }](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4N_8!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8fce6213-ea8e-4bdb-b984-185412332e62_538x208.png)

Thanks very much for this, Marshall. I haven't thought about Sibelius for decades. I first listened to him in my early twenties, and I don't have any of his music to hand now. You've persuaded me to order the last symphony you refer to. All the best to you (and to Pepper!) , Neil