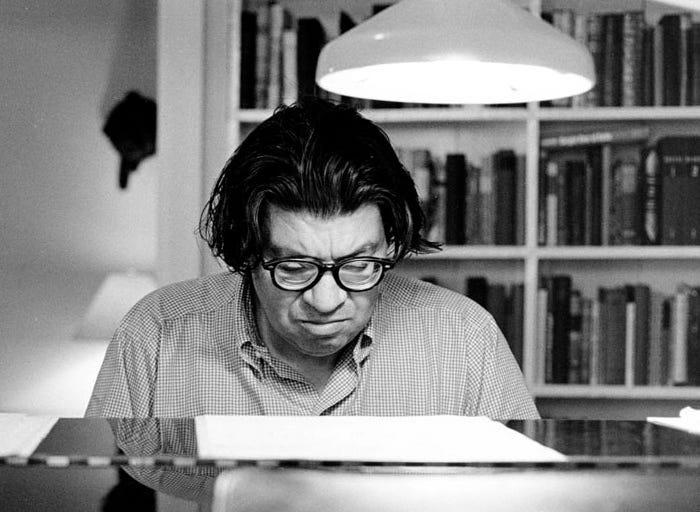

Morton Feldman

"For years I said if I could only find a comfortable chair I would rival Mozart"

If you are unfamiliar with Morton Feldman, he was an American modern classical composer whose great contribution to music was that his best compositions freed themselves of length (by getting extremely long), and he eventually wrote in only one volume level: the quietest possible. His music was an extreme on two different spectra that has not been approached or imitated.

If you don’t know his music, I recommend plunging into the deep end. Try Triadic Memories, an 80-minute solo piano which Feldman described as “probably the largest butterfly in captivity,” where the piano imitates wing-beats wishing to be free, and at times, feels like an extreme take on Erik Satie’s concept of eternity by actually trying to be that long (an early untitled piano piece, from the 1940s, tries hard to be a Gymnopedie).

Or, if you need more textures than just piano, try the 80-minute Piano and String Quartet, where the strings feel like a ghostly echo behind the piano, which itself is playing melodies that have been parsed out into their molecules. Ghosts upon ghosts upon ghosts upon ghosts; never scary, always there.

Aki Takahashi performs the first-ever recordings of both—the latter with the Kronos Quartet—released in 1989 and 1993, respectively, which must be among the best-ever albums released during those two years. (Takahashi also has the most unique interpretation of Schubert’s final sonata that I’ve heard since Svjatoslav Richter some 35 years before her.)

Or, if you want even more textures, try Crippled Symmetry, 90 minutes long this time, composed for piano, flute, celeste, vibraphone, and glockenspiel, where Feldman somehow removes the brightness of the metallophone instruments so that they inhabit the same endlessly spiraling hallway of his solo piano pieces.

One way to think about Morton Feldman was that he existed in a plane by himself between the two dominant nexuses of the New York City avant-garde: minimalism and indeterminacy. He is neither a minimalist, nor an—erm—indeterminant. (Feldman himself referred to his music as “between categories.”) Born in New York City in 1926, Morton Feldman belonged initially to John Cage’s school of experimentalism, whom he met in a chance encounter after a performance of Anton Webern’s Symphony. His early pieces like Three Dances and Figure of Memory are full of Cage’s ideas, including using prepared piano, chance compositions, and silence, and he adopted a graph notation where performers selected what notes to play based on given criteria.

I say ‘belonged initially’ because Feldman soon moved to that aforementioned plane away from John Cage. Instead of leaving any sound to chance, Feldman felt the need to precisely notate everything in order to present sound as a picture, leaving as little room as possible for interpretation or improvisation. Indeed, he surrounded himself with a lot of painters (a well-travelled quotation from Feldman: “If you don’t have a friend who’s a painter, you’re in trouble.) and tributed them in turn, notably Mark Rothko and Philip Guston. Feldman’s late-period works can be interpreted as the abstract expressionists in sonic form: deceptively complex and engulfing.

At the same time, he was separate from the minimalists that, from a glance, seem to be kin. If Feldman could be compared to the minimalists, it’s only because his compositions paralleled theirs by getting longer and longer. Otherwise, the New York City minimalists—Steve Reich, Philip Glass, La Monte Yonge, and Terry Riley—were mapping out discovery through repetition, and Feldman did not repeat. Philip Glass famously encouraged audiences to walk in and out of the four-hour opera Einstein on the Beach as they saw fit, but Feldman would demand a stillness from his audiences for pieces like String Quartet No. 2, which was even longer at six hours. It never seemed like a competition of male ego between Feldman and the minimalists to see who get longer and longer. Instead, it genuinely felt like he needed more and more time to get his points across, rationing the increasing lengths of his compositions by claiming he was “tired of the bourgeois audience,” or “what the world doesn’t need is another twenty-five minute composition,” or, quoting French composer Edgard Varèse, that people “don’t understand how long it takes for a sound to speak.” Having read his collection of writings, Give My Regard to Eighth Street, Feldman could be, by turns, funny, obtuse, and profound.

‘Demand’ feels like a strong word. Although certainly Feldman’s late pieces are a marathon for the performer in length (the audience get off easy by comparison), he is never imposing (despite the epic lengths of his compositions) or difficult. It is not a challenge to listen to him. You are free to do whatever you want, and I encourage people to seek out different recordings of the best Feldman. With pieces that long, even the slightest variations of tempo will have a large impact overall; hence why Aki Takahashi’s performance of Triadic Memories barely breaches an hour while the average is closer to 75-90 minutes. More recently, Philip Thomas, whose five-disc box set of Morton Feldman piano pieces is the thus-far definitive piano Feldman collection (not only because Thomas unearths previous unexplored compositions), has explicitly stated that it is okay for listeners to occasionally walk away from these compositions that demand prolonged periods of intense concentration, and more radically, he invites listeners to turn up the volume — within reason, of course. Frankly, no one would have dared say that during Feldman’s lifetime, not when he was instructing his performers to play him quieter and quieter (quoting Alex Ross’s essay on Feldman, “American Sublime,” “Legend has it that after one group of players had crept their way as quietly as possible through a score of his Feldman barked, ‘It’s too fuckin’ loud, and it’s too fuckin’ fast’”).

It’s not that his compositions are void of repetition either, but the rhythm of repetition (if any) is irregular, and formal development is not bothered with. Compositions don’t end, they simply run out. Feldman’s compositional style used what he called “patterns,” which he elaborated as “self-contained sound-groupings.” His pieces in his late period often creates a rhythm out of alternating patterns and silences, each pattern slightly tweaked compared to previous iterations—changing the rhythm or voicing, for example—such that that composition feels like a natural, living organism, and less a repetitive ambient piece. With the music turned down low enough, it’s hard to tell just when the pattern ends and the silence begins, as if one were just the extension of the other, the silence a decaying sound pattern, and the sound pattern a different kind of silence.

But treated as background music (“lo-fi classical to study to”) and having your attention wander in and out, and you will miss more in a Feldman composition than if you did the same on the aforementioned Cage or minimalists. In his essay on Feldman, “In Dispraise of Efficiency,” Kyle Gann once wrote of the minimalists that “There was a pop music aspect to them that later turned into ambient music.” What’s weird is that the minimalists could be loud and punk rock fast and was eventually well-incorporated into rock’s bloodstream while Feldman’s music is dynamic-less and intensely quiet, and yet, it’s the minimalists that Gann compares to ambient music. Because Feldman’s songs aren’t made up of repeating cells, every second not paying attention is a second that’s physically lost. By concentrating so intently on sound that is barely there is likely why poet Frank O’Hara said that his music, “sets in motion a spiritual life which is rare in any period but especially so in ours.” O’Hara was a great friend of Feldman’s, and Feldman wrote For Frank O’Hara in 1973 after the poet’s death in 1966; it’s a work of pure mourning, of sharp and eerie and strange tones that I don’t associate with the poet, and then a sudden, intrusive, thunderous drum-roll to signal O’Hara’s sudden death after being struck by a jeep.

In addition to Frank O’Hara, Feldman tributed many fellow composers, painters, and close friends, many of which were composed in the last decade of Feldman’s life:

For Aaron Copland, a solo violin piece, is an anomaly in two ways: first, it’s only 5 minutes in length, but it exclusively uses white keys, abandoning Feldman’s reliance on chromatics;

For John Cage doesn’t return to Feldman’s early works inspired by Cage; instead, it’s a series of haunted ghost dances between the instruments. Feldman considered it to be “a little piece for violin and piano, but it doesn’t quit.” 75 minutes turns out to actually be quite little compared to the tributes For Christian Wolff (3 hours) and For Philip Guston (4 hours, and not to be confused with the short, abstract ditty Piano Piece to Philip Guston) that came shortly after.

For Bunita Marcus is a solo piano piece and should be considered a duology of sorts in combination with Triadic Memories (i.e. the largest moth in captivity).

For Samuel Beckett applies his patterns, extreme lengths, and zero-dynamic sound paintings to a large ensemble, potentially glimpsing what Feldman might have done in the 90s, expanding his chamber set-up for doubled woodwind quartet, brass septet, string quartet, harp, piano, and vibraphone. Feldman had met with the Irish playwright and bonded over a mutual hatred of the opera, and thus, naturally collaborated to produce the opera Neither, which, like Philip Glass’ Einstein on the Beach, feels categorized as under ‘opera’ for lack of a better term: only one singer, blasting out Beckett’s text usually one syllable at a time, set to a far more apocalyptic Feldman than ever, a fitting match for someone that I associate with the death of language, the death of happy days, and the death of everything.

And yet, one that’s not mentioned nearly enough—not recorded nearly enough—is For Franz Kline, written in 1962 (i.e. his early period), a 5-minute piece all muffled tones behind glass in tribute of the American abstract expressionist whose use of whites and blacks must have surely influenced Feldman’s use of sound and silence in his later years.

Morton Feldman passed away in 1987 from pancreatic cancer. His last solo piano composition, Palais de Mari, was written the year prior, applying the same techniques and sound of Triadic Memories and For Bunita Marcus but presented in a third of the time. It turns out the world did need just one more 25-minute composition. Piano, Violin, Viola, Cello

Consider Feldman at his peak, at once, the greatest liberator of the New York City avant-garde. They were all deconstructionists at heart, but Feldman removed more than his contemporaries. In order: he removed the construction process, then the melody, then the rhythm, then the tempo, and then the volume. As opposed to the minimalists, his music was in a constant state of change — while being paradoxically perfectly still. As opposed to Cage’s fascination with silence, Feldman was a great lover of sound: pure sound, glorious sound, still sound, changing sound, surround sound.

Guess who else is now on this Substack train

Toot toot