Of all the major prog rock groups, Pink Floyd were the least-fun prog rock band ever. Is that disputable? Their music became increasingly self-serious, and pretentious as a result, whereas most prog rock really isn’t pretentious at all despite what people would have you believe — it’s just dorky! (I mean that affectionately.)

Insofar as prog rock could be defined as Britain’s very ambitious attempt at making rock high art—expanding on what the Beatles and the Who did in the late-60s on albums like Sgt. Pepper’s and Tommy—by, for example, layering sounds into symphonies and making albums play like ‘more’ than a collection of songs, and most obviously, by integrating classical music’s complex time signatures, then of course Pink Floyd is prog rock. Here’s the thing: I think that’s a very shallow read of prog rock, and while a lot of prog is very consciously complex, prone to over-conceptualizing and ‘look at me’ classical sections, the very best prog still ripped, plain and simple. It appealed for the same reason that rock originally appealed: base desire to hear music with a good fucking beat and a flashy solo, just with an additional desire to hear some jazz and classical.

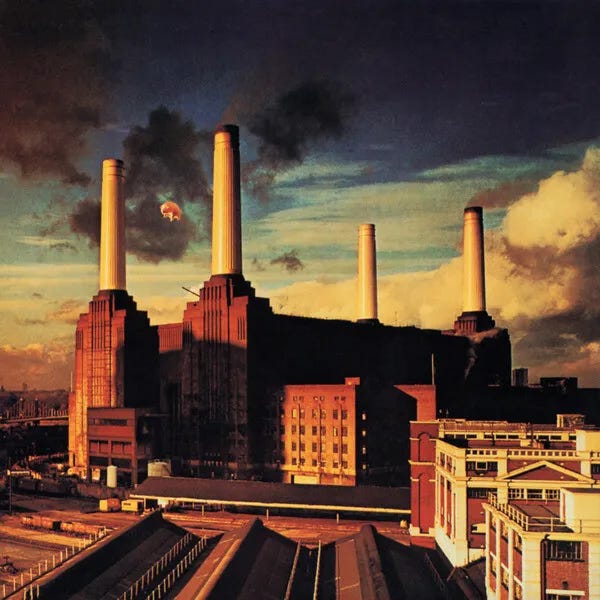

When Pink Floyd made the move to prog around 1971, they stopped ripping, at least, until Animals which was their last great album anyway. To use a point of comparison, Radiohead rocked louder and more often, an embarrassing charge. What Pink Floyd did instead, even under Syd Barrett, but especially under Roger Waters, was pure atmosphere: a lot of long build-ups and cathartic releases—they have songs that are almost post-rock—and David Gilmour as a guitar player was more about tone than anything else; notes-wise, he was as economic as they come.

What I love about Pink Floyd and the other prog rock acts is that they represented a time when complex music could actually be popular: that The Dark Side of the Moon managed to sell some 40 million copies as one of the best-selling albums of all time is no small feat for an album with barely any individual songs or any distinct tunes. (Of course, having iconic art that could easily be put on a t-shirt or converse shoe didn’t hurt either; Pink Floyd’s secret weapon was Storm Thorgerson’s artwork and I hope they paid him millions.)

The atmosphere of Pink Floyd’s major prog rock albums is unfortunately offset by Roger Waters’ puddle-deep philosophies and overbearing ego. Jean-Paul Sartre actually got it wrong, hell is not other people, hell is being trapped in a room with Roger Waters, Eric Clapton and Van Morrison to talk about politics, immigration and life-saving lockdowns. Topics like money, the music industry, politics, war and (um) walls, are all worth discussing, yes, but it’d take a smarter person than Roger Waters to pull them off. The smug irony-cum-now-hypocrisy of “Money” has made it so that I’ll never enjoy that 7/4 riff; shame, because those cash register were a smart (if obvious) idea. So I respect people who think Pink Floyd was at their best when Syd Barrett was part of the band, but I can’t join their cause: there’s just less there. Not just less albums—that too, obviously: there’s only two—but less tone colour, less compositional rigour, less epic sweep, less less less of everything.

One thing I’ll say is that for all the talk about Roger Waters versus Syd Barrett, and the praise that David Gilmour gets as a guitarist, keyboardist Richard Wright and drummer Nick Mason get shafted: reading reviews of the band, you’d have no idea how integral and tremendous they were to the band’s sound, at least, before Roger Waters started to edge them out (going so far as to kick Wright out entirely while making The Wall).

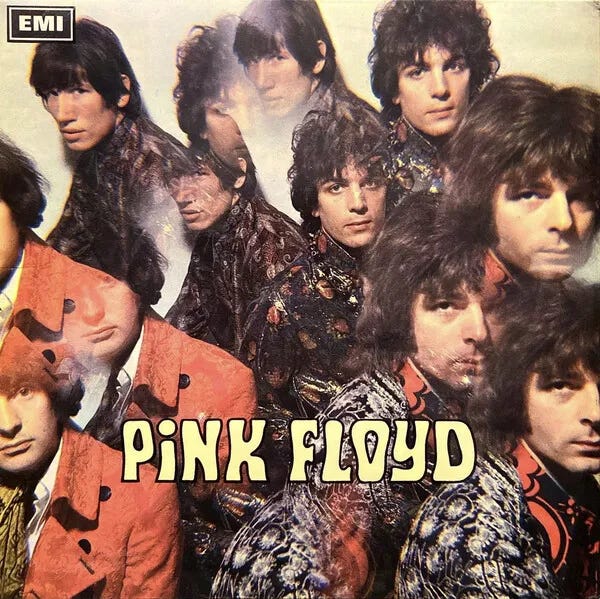

They got their feet wet as the original house band for UFO Club, a venue for London psychedelia where Soft Machine, Arthur Brown, Procol Harum and the Incredible String Band also performed — and, allegedly, Jimi Hendrix on one occasion. Legendary DJ John Peel was a frequenter. After generating enough buzz, they signed onto EMI, where they released their first singles, “Arnold Layne” and “See Emily Play,” neither featured on the U.K. version of their debut album (where no singles were released), but the latter was included in the U.S. version at the expense of one of the best songs being scotched: “The Bike.” Thus, the U.K. version is where its at.

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn is a weirdly unthematic album: the two side openers demonstrate the band’s interests beyond earth (‘space rock’), and then as the album starts to wind down, Syd Barrett composes a lot of whimsical songs that feel like children’s dreams—or are they nightmares—come to life and sung like nursery rhymes: “I know a mouse, and he hasn't got a house / I don't know why I call him Gerald” could’ve been a scene from Alice in Wonderland. Had 10-minute centerpiece “Interstellar Overdrive” been released by a German band, no doubt it would’ve been filed under krautrock—it seemed like every band I researched for my Krautrock book mentioned Pink Floyd as an influence, and notably Ash Ra Tempel may never have started if not for a chance run-in with Pink Floyd roadies—but it’s the shorter, whimsical pieces that endear me the most. Other bands might have made “Astronomy Domine” or “Interstellar Overdrive,” but only Syd Barrett could’ve written “The Gnome,” “The Scarecrow,” or “Bike.” The cuteness is surface-level—“A gnome named Grimble Crumble,” Barrett sings, rolling his r’s for the last word; Nick Mason’s percussion tones and Richard Wright’s sky-reaching Farfisa organ on “Scarecrow”—but there’s clearly something off: the scarecrow is revealed to be “sadder than me / but now he’s resigned to his fate” while “Bike”’s romantic gesture is punctuated by drums that sound like gunshots.

Whereas Barrett wrote all of Piper save for the instrumentals (credited to the whole band) and “Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk,” written by Roger Waters, he barely contributes to A Saucerful of Secrets as his mental health had deteriorated so much he left the band after the album; where once his live performances were animated, he was now lifeless on stage, and deemed a liability by his band-mates to the point that they neglected to pick him up en route to a performance. For his sole composition, closer “Jughead Blues,” Barrett was adamant about incorporating the Salvation Army International Staff Band but arrived late for rehearsal and told them to play whatever they wanted, leaving producer Norman Smith to score their parts; structurally, the song plays like “The Bike” but it’s far more touching given Barrett’s mental status: “It's awfully considerate of you to think of me here / And I'm most obliged to you for making it clear that I'm not here.”

To pick up the slack, guitarist David Gilmour was brought in, and so Saucerful is the only album that features both Gilmour and Barrett, old school-mates and college jam buddies. Elsewhere, Richard Wright’s “Remember a Day” features some beautiful keyboard harmonies. “Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun” is a peaceful pool of drums and keyboards that reminds me of something John Peel once said about the UFO Club atmosphere, “It wasn’t like clubbing these days. Rather than dancing around, you… obviously, some people danced about in a fairly idiotic manner… but mostly you just lay on the floor and passed out really”; lie down and drift away. “Corporal Clegg” would be the first of many Roger Waters songs to be about war, and though the kazoo is off-putting to some—the song is possibly named after kazoo-inventor Thaddeus von Clegg—it’s an honestly interesting texture and the song wouldn’t be as good without it. (Second-best kazoo-aided tune of ‘68, after the obvious one, of course!)

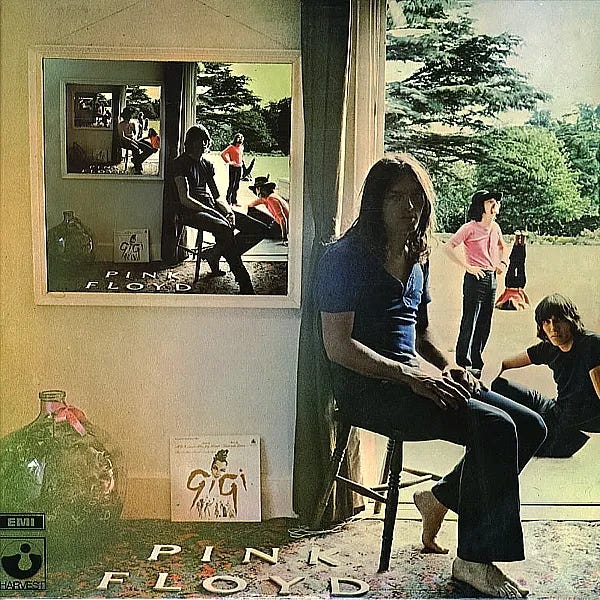

Film soundtrack More would be their first album without Barrett, completed on the quick in two weeks with no access to a dubbing studio, so no surprise that it’s half-instrumental and a lot of it feels like wafts. Occasionally lovely wafts though, particularly “Crying Song,” and “The Nile Song” is among their heaviest, straight-forward rockers. Released later that same year, Ummagumma gets knocked for being a live album with tacked-on studio experiments on the second side — or a studio album with a tacked-on live album. The way I see it, Pink Floyd was an experimental band at heart, and they wanted to experiment in studio without scaring away audiences, so they packaged it up with a live album. Besides “Careful with That Axe, Eugene,” a live performance of a b-side that is one of the genuinely scary pieces of psychedelic rock (you’d think there’d be more), the live set doesn’t interest me. I’m not saying the studio disc is necessarily better as there’s a lot of timbres going nowhere in Nick Mason’s offering, where he offers his wife some space to play flute. That’s also partly true of Roger Waters’ “Several Species of Small Furry Animals Gathered Together in a Cave and Grooving with a Pict,” which he stresses in interviews that all animal sounds were human-generated, but even that one has the portion early on where it sounds a looped voice goes “Come back” over the cacophony that sounds like early Animal Collective to me. The most accurately-rated Floyd album: neither underrated nor overrated.

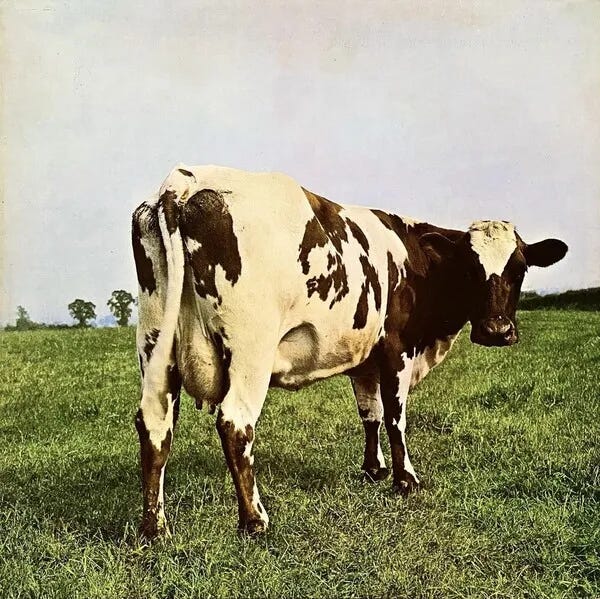

A similarly democratic approach was taken for Atom Heart Mother, with Waters, Wright, and Gilmour all contributing one short song in between the two long bookends. Neither Roger Waters nor David Gilmour have reflectively positively on the album as a whole, although Gilmour thinks fondly of “Fat Old Sun,” which is the album’s best: pedal steel guitar notes twisting and bending skyward, and an electric guitar solo that feels like a genuine release. Richard Wright’s “Summer ‘68” is another Sgt. Pepper’s worship whose horns feel a little too easy. The 6-part opening suite should not be considered among the band’s best long-form compositions. Instead, it’s a piling-on of textures, each more ridiculous than the last: Wright’s prog organ that actively detracts from the cello solo on the portion titled—I kid you not—“Breast Milky” (prog rockers were so fucking horny), then brass, then choirs, and even a noise section.

The same cannot be said of the side-long closer, “Echoes,” of their next album Meddle, whose high-detail sound and ambitious scope would be the basis for the classic prog run. Some consider Meddle a transitional album but I demur: it ends their transitional, experimental, post-Barrett phase. Curiously, my opinions of all the Floyd albums haven’t budged a bit with the exception of this album which gets better and better every time I hear it. I even have warmed up to “Seamus,” everyone’s favourite spanking child, a 2-minute acoustic blues song that the band spent time to train the titular dog to howl-harmonize (not really) with the music because it’s somewhat reminiscent of their Syd Barrett days although it’s doubtless that Barrett would have gotten more strangeness out of the song. “One of These Days” is “Interstellar Overdrive” that goes even further into overdrive and predicts a heavier album than what we actually receive, which is far more graceful and even idyllic than you’d think they were capable of. “A Pillow of Winds” and “Fearless” are the band at their most beautiful and least pretentious. The former is what Gilmour was working towards on the previous album’s “Fat Old Sun” while “Fearless” contains those ringing chords from Roger Waters on acoustic guitar, a cute little musical motif that matches the lyric about “climb[ing] that hill in my own way.” “San Tropez”—the only song here not written by a combined Waters and Gilmour as they were finally working as a team for once—is a jazz-inflected pop song with a gorgeous instrumental section at the 1:15 mark.

Obscured by Clouds is another film soundtrack for La Vallée, and far better than Floyd because they now have direction; there’s also less instrumentals and more fleshed out songs, including the 3-song run from “Burning Bridges” through “Wot’s…Uh the Deal.” Mid-tempo rocker “The Gold It’s in the…” and Beatles-esque “Wot’s…Uh the Deal” feel like their most overt appeals to radio, ever. “Mudmen” is an instrumental reprise-of-sorts of “Burning Bridges,” and Gilmour’s guitar solo is a little too squealy in its attempt to soar high, but he redeems himself on “Childhood’s End,” the last Pink Floyd composition entirely written by Gilmour.

Reports of The Dark Side of the Moon’s concept have been overstated: it’s just a cohesive listen that touches on very different existential themes, and it ultimately works to the album’s advantage that there is barely any focus on words: not only are three of the 10 songs instrumental, but there’s no words during Clare Torry’s outpouring on “The Great Gig in the Sky” either. (And so to hear Roger Waters drone on and on about how everything will be eclipsed by the moon on the final song is a letdown.) The best parts of this album are purely instrumental, which should not be surprising as Waters was neither a tuneful or powerful or a particularly noteworthy vocalist in any way, but also not any Gilmour solo either. I cherish moments like Gilmour’s pedal steel guitar on “Breathe” moving out of 60s’ country and into 70s’ space (it’s a neat trick that only a few artists figured out, including King Sunny Adé, which is that the pedal steel guitar has a naturally spacey sound); the spacious mix of the mini-symphony of clocks and Waters’ muted strings that open “Time” that give way for that piano to float you home from space; the wash of synths in the intro of “Any Colour You Like.”

But my favourite song here, and has been the case since as long as I’ve known the album, is “On the Run,” a brooding instrumental that predates a lot of art rock instrumentals near the decade’s end (i.e. Bowie, Eno, and Japan), and sounds like some of the krautrock that Pink Floyd had inspired in the first place. “On the Run” is mostly just a synth and a lot of studio gimmickry, but the additional effects—a metallic groan, the whirr of a helicopter overhead, a laugh—creates an illusion that you’re actually on the run from something sinister. You could say that the majority of songs from The Dark Side of the Moon ‘work better in the context of the album,’ which is true as almost all of the songs aren’t meant to be played on their own, but I’ve always enjoyed “On the Run” by itself, and the same goes for the similar atmosphere of “The Happiest Days of Our Lives,” both interlude-style tracks that have been given such care that only a complex atmosphere band could have given that they shine plenty on their own.

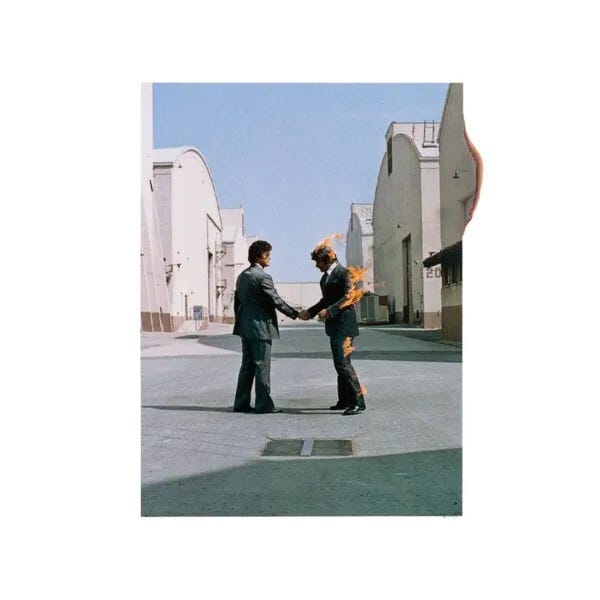

Wish You Were Here used to be my favourite Pink Floyd album on account of it being the most touching. The only touching one. Robert Christgau quipped in his review of OK Computer that Wish You Were Here was his favourite Pink Floyd album because “It has soul, that's why—it's Roger Waters's lament for Syd, not my idea of a tragic hero but as long as he's Roger's that doesn't matter,” and that sums it up: as egotistical as Waters was, this is the one album released in their golden prog era where his personality doesn’t clog up the experience. Almost, anyway. It makes no sense to me that an album with songs as touching as “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” and “Wish You Were Here” splices itself quite literally in half to make room for two songs about the music industry, which you can pretty much guess Waters’ position from the title of “Welcome to the Machine” alone. If you’re so dissatisfied with the greasy label execs and fickle audiences, why not go with the original intended product of a musique concrète album played on household objects? Ah, right: “Money, it’s a gas.”

Remnants of the botched Household Objects project can be found on the 2011 Immersion Box Set version of Wish You Were Here, which, of course, a ton of Pink Floyd fans bought at exorbitant prices even though no one needs it. You do get Animals’ “Sheep” and “Dogs” in their embryonic “Raving and Drooling” and “You Got to Be Crazy” forms, played live at Wembley in 1974, interesting because one of the pulls of Animals is that it was so ‘with the times’ of the punk era and these are proof that Animals was already gestating three years prior. You also get an alternate version of “Have a Cigar” to compare the band’s take on the song but without Roy Harper to the album version, as well as an alternate version of “Wish You Were Here” with Stéphane Grappelli, whose playing was lobbed off in the album version. Rightfully so; country twang as the song might have, a fiddle doesn’t belong.

“Welcome to the Machine” is curious since this now-mega-successful rock band was experimenting with what actually does sound like industrial music. The incessant throb from Waters’ bass following that loud wash of analog synth is arguably the most interesting sonic on the entire album even though it plays itself out really quickly and the song itself just clomps along afterwards. “Have a Cigar” is even worse, highlighting that, even though David Gilmour was obviously very much inspired by the blues, had he been tasked to make more straight-forward blues music, it wouldn’t have been very good. The Minimoog riff sounds out of place on a song like this (it should have been played on the guitar), and while it’s interesting that the band handed over vocals to Roy Harper, it’s not exactly like Harper’s voice is that much different than Gilmour’s or Waters’ voices, so what was the point?

“Wish You Were Here” is the rare 70s’ radio-approved ballad that seems impervious to the effects of overplay to me. Love that, “Money” aside, it might be the most straight-forward piece of radio music that the band made during this era pre-The Wall, but it’s still very much in the spirit of classic Floyd: atmospheric and patiently built towards. The first minute reminds me of KLF’s Chill Out: a surreal drive through farmland where everything is chilled out, and it’s not until that first minute has passed where the second guitar comes in, crisp and clear, and another forty seconds after that until David Gilmour starts singing. And the drums are sat on for a little bit after that, really highlighting how meaningful the words are to this band. The repetition of the word ‘so’ in “So, so you think you can tell / Heaven from hell? Blue skies from pain?” makes this song play like some great conversational speech. The build-up means that the simple song is allowed to be stretched to five and a half minutes without ever feeling like it’s spinning wheels; the release of the verse, the guitar solo and then the chorus all feel that hard-earned. A lesser band would have repeated the chorus at least one more time and taken away from how special it is: “We’re just two lost souls swimming in a fishbowl, year after year.”

The decision to break up “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” from one 25-minute composition into two bookends might seem puzzling, and indeed, Gilmour wasn’t a fan at first. But by 1975, the world was already starting to shy away from overly complex progressive rock, with critical acclaim for Yes and Jethro Tull both cooling. (The party line that punk rock kicked prog rock’s ass out the door, with Johnny Rotten famously wearing a t-shirt with the slogan “I hate Pink Floyd,” is just that: a party line and not true, or else Rotten wouldn’t have loved Hammill/Van der Graaf Generator as much as he did. The decline of prog, and the advent of punk were two separate events that just happened to coincide.) By splitting “Shine” this way, Pink Floyd, who took up the mantle as the world’s biggest band in the world with The Dark Side of the Moon, made their epic composition feel more approachable while retaining that ‘epic-ness.’ An impressive feat, truly! “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” feels like a distillation of everything good about The Dark Side of the Moon—the sweeping atmospherics; “The Great Gig in the Sky”-style vocals during the opener’s climax; “Money”’s funk groove in the middle of the eighth section—but replacing the loose concepts with one that’s much more emotional for the band.

As mentioned way up top, I pinpoint 1975 as the year of prog’s decline: Peter Gabriel parted ways with Genesis, and King Crimson had disbanded the year before, and the output from everyone else just wasn’t as fertile as it was back in ‘72 when everyone seemed to be cranking out two albums apiece. So when I say Wish You Were Here is the best prog album of ‘75, it’s an easy call for me to make—ditto Animals for ‘77—although Triana’s flamenco-prog El patio gets the silver that year.

People gave Jon Anderson so much shit for Tales from Topographic Oceans, lyrics gleaned from a footnote of Autobiography of a Yogi, but Roger Waters gets a free pass for reading George Orwell’s Animal Farm and simplifying it down for Animals, how about that? Double standards, says I!

That this album has to generalize Animal Farm—most notably by removing the actual characters from it—outlines a pretty obvious difference between lyrics and text, which is that you’re just not able to get as deep, and so Pink Floyd does what Pink Floyd can only do: call out society and play a long guitar solo. The premise is the same as Orwell’s book: the dogs represent the police state, instilling fear on the population on the rest of the farm animals; the pigs represent the greedy politicians; the sheep represent the dumb-but-content rest of population. Orwell’s book is also allegorical and extremely critical of the Russian Revolution; Pink Floyd aren’t super-critical of anything in particular. Okay, they call out Mary Whitehouse (not the White House, which I originally thought) on “Pigs (Three Different Kinds),” or Thatcher (on live versions). At any case, it’s a simplistic read, and ultimately, too vague of an anti-government sentiment. Is this album better than Topographic Oceans? Sure, but not by much, and it’s not that much less pretentious either.

The appeal of this album is not Animal Farm, not Waters’ political commentary, not that Pink Floyd could make a nihilistic progressive rock in the spirit of punk rock at a time when the prog rockers were getting increasingly irrelevant. Instead, the appeal of this album is incredibly easy: it rips. There’s no atmosphere to speak of—only David Gilmour’s arcing guitar notes on “Dogs” recalls “Shine On You Crazy Diamond”—which is in stark contrast to their previous records. And because it rocks, it’s my favourite Pink Floyd album, who compared to Yes, Genesis or King Crimson were less likely to rock out for as extended a period of time. “Sheep” might be my favourite Pink Floyd song, with David Gilmour’s bass turned from a full-speed throttle into a gallop. And like Wish You Were Here, Animals is only five songs, but because two of those are merely 90-second bookends, it feels even more focused; more intense.

But it’s also the Pink Floyd album where Roger Waters’ mind-numbingly simplistic nihilism starts getting overbearing, and it’s so obvious he holds his entire country in contempt: “Only dimly aware of a certain unease in the air”; “Meek and obedient, you follow the leader / Down well trodden corridors into the valley of steel.” So, of course, he layers the pig noises thick on “Pigs (Three Different Ones),” the only pox on the album. (Just the effects; the song itself rips.) And while I’m on the quibbles, obscuring the interlude of “Sheep” in a vocoder and speeding it up and rendering what would have been the most shocking line on the album undecipherable, “He converteth me to lamb cutlets,” was a bad move.

Don’t discount the bookends, which are surprisingly graceful for this band at this point in time. For such a short song, it certainly goes through a ton of chords (good beginner guitar strum song) and lends it a fine melody, and I find the flip of “If you didn’t care what happened to me” in the first song to “You know that I care what happens to you” to be genuinely touching.

Back to “Sheep,” there’s a release in the final verse where Roger Waters stops using flowery language (like “Wave upon wave of demented avengers / March cheerfully out of obscurity into the dream”) to deliver the song’s simplest lines: “Have you heard the news? The dogs are dead!” But the release is—as always with Floyd—ambiguous: “You better stay home / And do as you’re told / Get out of the road if you want to grow old.” The coup d’etat feels like a positive thing, but it also feels uncertain for many of the sheep, and the song’s final few minutes manage to be the most bad-ass ride-out ever while also sounding incredibly tense.

The Wall is an obnoxious album all-around, marking the end of the band’s run as Richard Wright was dismissed. Roger Waters writes practically every second of the record—Gilmour has his hands in only a small handful—so where on previous records, his ego and voice were tempered by the rest of the band’s atmospherics, they are now front-and-center as the band move away from cinematic epics to boring, bite-sized songs. This is not a prog album; there’s nothing progressive about it.

For all the talk of the album’s nihilism—you see, it’s a loop!—I don’t think it gets dark enough, especially when one of two of the album’s most famous songs features a children’s choir rallying against abusive teachers; I think ‘joyless’ is a more apt description. The Who’s Tommy might get lambasted as being over-the-top, but it’s a rock opera — why did you expect anything else? And at least Tommy’s brief interludes were musically worthwhile, unlike, say, “Stop,” and is “The Trial” not over-the-top regardless? If it weren’t for a reprise of the riffy opener, and “Comfortably Numb,” it’d be more apparent that the second disc is a Frisbee akin to Genesis’ The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, which had a far less cohesive story sure, but was a far richer album overall: merging dark psychedelia and progressive rock in a way that you’d think Pink Floyd might’ve tried but never did. I can’t get over the fact that Roger Waters put a 5-minute song-conversation between the protagonist and his mother, but gave the mother’s parts to David Gilmour so it sounds ridiculous; “Goodbye Blue Sky” has some very portentous chords, but the ‘Did-did-did’ hook sounds—again—ridiculous, and these are songs that I consider highlights!

The concept of the album was born from Waters wanting to erect a wall between him and his audiences after a spitting incident, and it certainly worked on me: I have zero interest in the albums that came after. The Final Cut dredges up material that wasn’t good enough for The Wall, along with some new material Waters brought to the table. “Your Possible Pasts” has an embarrassingly corny use of echo (“CLOSER!…Closer!…Closer!”) in its choruses; Waters is really hamming it up on “One of the Few” (“To land on your feet / What do you do to make ends meet?” he asks, spitting out those t’s so harshly you can see the spit bubbles). Floyd bottomed out for A Momentary Lapse of Decency, which feels like it should’ve been released a year earlier to align Pink Floyd with basically every other rock legend who dropped their biggest turds in 1986. The David Gilmour-helmed The Division Bonghit, featuring old-time keyboard player Richard Wright, plays like a corporate apology by comparison, but boring is its own version of bad. Gilmour has a good line about The Final Cut, “[Waters] wasn't right about wanting to put some duff tracks on The Final Cut. I said to Roger, ‘If these songs weren't good enough for The Wall, why are they good enough now?’” but I guess he forgot all about that when he released a bunch of unreleased material from The Division Bell for The Endless River.

Not to end on a dour note once again! Pink Floyd is ultimately a band I get less out of then other psychedelic bands or more-proggy prog bands, and it truly feels like there are no interesting takes to be had about Pink Floyd. But hey, prove me wrong: let me know your Pink Floyd hot takes! The biggest limitation for a band like this with someone who thought he had as much to say as Rogers Waters is that the majority of their songs play like this: Roger Waters going ‘This thing is bad!’ and then David Gilmour dropping a 5-minute guitar solo.