It’s a shame that Pizzicato Five aren’t more of a household name outside Japan because bottom line, they had an incredible run in the 1990s, putting out two of the best albums of the decade. Yes, they had a discography that is confusing in its sonic twists and turns, line-up changes and the fact that you have to parse out the studio albums from the myriad remix albums and TV soundtracks, and not helping is that their records aren’t accessible as many of their albums have only been reissued once outside of Japan if at all, and certainly not available for streaming. (Even before the two greatest Canadian musicians hopped off, there were plenty of reasons not to use Spotify beyond them paying their artists peanuts: no De La Soul, no Joanna Newsom and no Pizzicato Five. A trifecta of quirk!)

Were I to describe Pizzicato Five/the sub-genre of Shibuya-kei (named after a district in Tokyo) to which they are a big part of, I’d say it’s pop music that loves pop music. Even more than city pop, Pizzicato Five crate-dug past funk and disco and into all forms of 60s’ pop: bossa nova, soul, lounge, girl group and jazz. And the term crate-digging is especially relevant for them considering they would discover hip-hop sampling for This Year’s Girl. Their debut single was backed by covers of Simon & Garfunkel and the Beach Boys while they would cheekily title songs after Western hits (i.e. “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” “Sex Machine” and “Magic Carpet Ride”) as if their own way of infiltrating the Western canon.

Having formed in 1979 by two then-university students Yasuharu Konishi and Keitaro Takanami, Pizzicato Five didn’t release their first album until the tail-end of the 1980s for lack of a vocalist until they landed on Mamiko Sasaki in 1984. Sasaki was replaced by Takao Tajima who didn’t kick around for long, and was finally officially replaced by Maki Nomiya in 1990 whose playful vocals would grace their best albums and see Pizzicato Five all the way to the end of their discography.

Here’s the guide with a quick note that I’ll only cover the studio albums:

Debut album Couples (1987) has that feeling that you just picked out a record from a used bin on a whim, giving you a bunch of cozy girl-boy harmonies and some well-appreciated horns and vibraphones and closely miced everything. The songs all work at an individual level but blend together well before the halfway mark but there are already a few well-appreciated sonic details: hand percussion perking up “They All Laughed” halfway through or the tuba blat of word-less “Party Joke.” The best song is the one that apes Vince Guaraldi’s “Linus and Lucy,” “Summertime, Summertime.”

Couples would have only been helped by the presence of their debut single/EP The Audrey Hepburn Complex from 1985 even if it wouldn’t have fit, but not to fret because their second album Pizzicatomania! released later in 1987 contains all three of those songs. “The Audrey Hepburn Complex” is a delight, bass-heavy piano chords contrasting with the merry-go-ground melody, the stitching together of two wildly different parts using plucked strings and cheap horns. There’s also a ‘clubmix’ cover of Simon & Garfunkel’s “The 59th Street Bridge Song” which actually does play like a club mix with the drum and bass while never subtracting from the original’s charms, and a cover of the Beach Boys’ “Let’s Go Away for Awhile” that practically sings even before Sasaki joins in on harmony. But the best song is brand new, the absurdly catchy “Action Painting” with a stomping drum part and a male cheerleader happily repeating Sasaki for the hook (“…action painting / ACTION! PAINTING!”); the orchestrated bridge is the sonic portrayal of Christmas morning. Elsewhere, note the piano throughout “September Song (Manufacture Mix),” capping off the verses with a 3-note melodic riff before turning into a pulse during the choruses.

Third album Bellissima! (1988) is ‘dedicated to Alberto Moravia and William "Smokey" Robinson,’ and so they toss out the more eclectic reach of their previous album for Motown-influenced cocktail arrangements that serve the singer instead of the song. The problem? The singer. Mamiko Sasaki is no more, replaced by male crooner Takao Tajima who is generic heartthrob as they come here, but not like the arrangements are dynamic enough in the first place (exceptions: steel drums swooping in to save the day on “World Standard”; tangle of backing vocals at the very end of “The Work of God”).

More than any of their previous albums, On Her Majesty’s Request (1989) really hints towards what’s to come; it even features Maki Nomiya on vocals on “Satellite Hour,” a song that goes on a little too long but is a very interesting arrangement of vocals bouncing around like they’re pizzicato strings and some phone beeps. The 60s’ pastiches are the best of their career thus far: “Bananas” is the best Brian Wilson tribute since, well, I guess Tatsuro Yamashito’s Beach Boys covers earlier that decade, while “Homesick Blues” seems to riff on Simon & Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson” (possibly referencing his blues songs on Paul Simon’s eponymous solo album). Meanwhile, “Spy Vs. Spy” looks ahead to “Twiggy Twiggy” (really dig Tajima’s squeezed ‘ooooh’’s on that song as well as the very cinematic backing vocals over the James Bond strings and booming tympani). There’s a three-song block near the end that seems like it’s going to be all covers which was sure to disappoint me when I found out they weren’t going to try Dionne Warwick’s “You’ll Never Get to Heaven” (good vocal harmonies in the middle) or the Rolling Stones’ “Let’s Spend the Night Together” (which is among one of the highlights regardless; energy aplenty) considering they generously sample “Sympathy for the Devil” earlier on “The African Queen” (which is not among one of the highlights).

A handful of songs from On Her Majesty’s Request would appear re-worked on the following Soft Landing on the Moon (1990) as well as some some songs from their previous albums including a hard rock (live) version of “Bellisima ‘90” and what sounds like a demo of “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” while a drum machine updates “Temptation Talk” into a 1980s’ R&B song. “Sex Machine” is a pretty lame attempt at Prince and the vocals muddle up the string arrangement of “Planets,” but don’t miss out on “They All Laughed” with another Maki Nomiya vocal (Rolling Stones’ country blues harmonica on a song that isn’t country blues at all).

Sampling in 1989 (De La Soul’s 3 Feet High & Rising, Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique) had outdone everything before it (and frankly about 80% of whatever came afterwards too, and even then I think I’m underestimating), and I think the influence must have travelled all the way to Tokyo because the feeling I get listening to This Year’s Girl (1991) is very much aligned to the spirit of those records. (Allegedly, this record was inspired by 3 Feet High & Rising; making the influence from De La to this record evident is that “Marble Index” starts with a quick rendition of ‘Chopsticks.’) Especially when some of the samples are time-tested funk bites that hip-hop loves like Sly & the Family Stone’s “Family Affair” (whose wobbly three note mini-hook turn “Let’s Be Adult” into a friendly jam) and James Brown (“Baby Love Child” and “Xxxxxxxxxman”).

I don’t think I’m exaggerating to say that every single sound is a hook, and the songs themselves all feel very distinct from one another: dulcet acoustic guitar off-set by a strange deep male harmony on “Baby Love Child”; ridiculous 60s’ spy film horns of “Twiggy Twiggy”; skating rink keyboard hook of “Marble Index”; yummy jazz flute of “Tokyo’s Coolest Sound.” This album leaves me feeling woozy just trying to remember them all. Why this is their best album though, is how well everything is mixed, in stark contrast to the more clinical production of Happy End of the World.

For example, think of the sugar-rush first few measures of “Thank You” whose acoustic guitar and percussion both dazzle aplenty (a hook) that still makes plenty of room for that hyper-active bass (another hook) or heavy hitting drums (yet a third hook) that soon come in. Every instance of a new instrument being added to the mix makes me think they can’t possibly shove anything more in there, and then they do. And then, you know, Nomiya starts singing. That’s also why “Xxxxxxxxxman” is my favourite song from the second half because just when you think it can’t get any better, the horn samples give way to disco strings that thicken up the groove. If you listen to the first few measures and then skip ahead to the 2:45 mark, it’s natural that they got from one place to the other, but it’s also unbelievable they did since the groove was good enough to begin with.

A note here that This Year’s Girl was released in September of 1991, and in the three months preceding it, Pizzicato Five release one EP at the start of every month (the summer of P5), each containing one great song and one of the “This Year’s Girl” sketches (hence why This Year’s Girl starts with the fourth one) among other goodies (some superfluous, including alternate versions of “Let’s Be Adult” and “Tokyo's Coolest Sound”). Those songs: This Year’s Model’s “Brigitte Bardot T.N.T.” (impossible not to shake a little bit to this song; incredible horns set to a ridiculous tempo); London-Paris-Tokyo’s “London-Paris” (more catchy male backing vocals; “London-Paris, London-Paris!”); Readymade Recordings “Kekkon no Subete (All About the Married Life)” (slow vocal jazz song from the early-60s as bossa nova was spilling over).

Sweet Pizzicato Five (1992) throws a wrench in their 90s’ run, a curve-ball follow-up to This Year’s Girl that arrived the following year that consists of only 9 songs, the average groove running around 6-7 minutes instead of the succinct pop of their previous album. The second song “Flower Drum Song” announces this record’s intention more than the opener: over a house thump for a beat and additional dubby effects, they lather Maki Nomiya’s vocals in echo so it’s constantly repeating, and the intent is made clear when the disco bass-line finally comes in: they’re trying to create their version of house music on most of this album, trying to make a diva out of Nomiya that doesn’t come off. There’s some good stuff here still: opener “Tout Va Bien” cutely interpolates the Beatles’ “Drive My Car”’s hook (‘beep beep, beep beep, YEAH!’); “KDD” uses a phone ring buried way deep in the mix to thicken the groove (reminiscent of early song “Satellite Hour”); a saxophone solo livens up “Funky Lovechild” over wah-wah guitar and even a speckle of sitar, but each of those charms wears thinner and thinner with every repetition.

Consider 1993’s Bossanova 2001 the follow-up to This Year’s Girl that Sweet Pizzicato Five wasn’t, except brighter and songier, exemplified by the fact that they’re sampling early Sly & the Family Stone this time on “Sweet Soul Revue” instead of There’s a Riot Goin’ On. “Strawberry Sleighride” takes a ‘beep-beep’ sound-byte (imitated later on by the bass) which is already catchy in itself, but then the chorus arrives and Nomiya sings “Isoide” in a wonderful 3-note melody as the backing vocals sweeten the deal: the lost spirit of all those girl group hits I adore from the 1960s, still kicking! It would be my favourite Pizzicato Five song if not for another one that I’ll talk about later on. “Eclipse” is arguably a remake of “Baby Love Child,” but it’s perhaps prettier and certainly warmer. They also get psychedelic too: “Magic Carpet Ride” features an exotic organ to add to the humid summer air while “Saga”—already a great song with the jazz flute and girl group harmonies—ends with a piano line that submerges the flute and gives the feeling that you’re by the water. That said, “Rain Song” is a clunker, featuring a nauseating amount of panning but it’s boring besides that anyway. “Sophisticated Catchy” could have been their motto over “A New Stereophonic Sound Spectacular.”

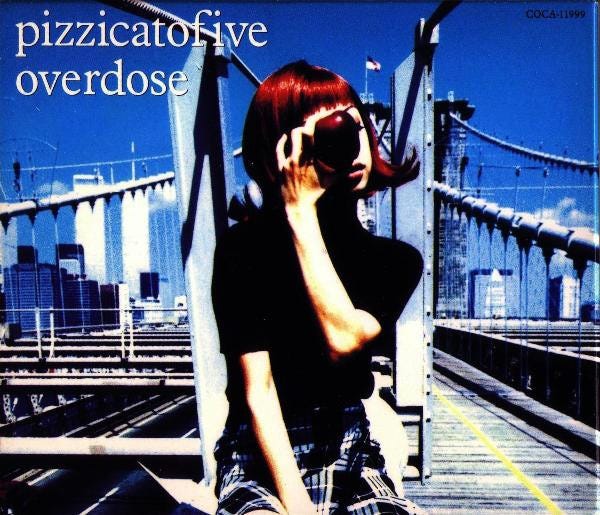

1994 was a big year for Pizzicato Five, with the near simultaneous releases of compilation Made in USA which was their first release on Matador to introduce them to American audiences (featuring a lot of material from This Year’s Girl and Bossanova 2001 but an inexplicably short run-time considering how many good songs they had lying around to choose from) and then Overdose, their highest-charting (#7) and best-selling album in Japan.

Founding member Keitaro Takanami is no longer here, leaving Yasuharu Konishi to write all of the music by himself whereas Takanami had contributed to almost half of Sweet Pizzicato Five and Bossanova 2001 which might explain this album’s slighter material: “If I Were a Groupie” and 10-minute house centerpiece “The Night Is Still Young” both feel like they’re spinning wheels after the first minute or so, and even opener “Airplane”’s 5-minute run-time doesn’t invite me to replay its nice organ or piano parts. And the same goes for “Hippie Day” which has a nice Latin acoustic guitar solo but little else of note. Worth pointing out is that “Statue of Liberty” features a rapped verse from Tagaki Kan that the song feels like it’s actively building towards with its horns acting as hype-men, one of the rappers that featured on De La Soul’s “Long Island Wilin’” from Buhloone Mindstate.

How I view Overdose is that it’s a good album with no great songs, whereas I view the following Romantique 96 (1995) as a lesser album overall but it has at least a few winners. Those highlights: “Contact,” a groove assembled from cheap machinery beeps and a whimsical synth-line that could’ve been from a synth-pop hit from the decade prior and feels like what they’ve been building towards as early as “Satellite Hours”; the drum-rolls of “The Sound of Music” that I swear are a sample of the Slits’ cover of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine”; the piano bridge after the French spoken word bit on “Tokyo, Mon Amour” (not to be confused with “Mon Amour Tokyo” on the next album). But most of all, closer “Triste” feels like it could have been a song from Bossanova 2001 with its uplifting horns and closing ‘la-la’s, and the piano groove make sure the song never stagnates when the horns aren’t punching. That said, “Welcome to the Circus” has a blaring one-note crescendo that actually has a circus feeling to it, but when Nomiya borrows the hook from “Sweet Soul Revue” (“Hora, revue ga hajimaru”), it makes me miss that song, while funky house cut “Flying High,” “Ice Cream (Mellow Mix)” and “The Secret Garden” all bop along pretty innocuously and don’t justify their over 5-minute run-times (over 6-minutes in the cases of the latter two), and those four songs alone account for more than one-third of the album’s overall run-time.

Happy End of the World (1997) was the first album of new material that was released via Matador in the United States, so it’s also their most popular album outside of Japan. It’s got some good ideas—“The World's Spinning At 45 R.P.M.” finally shifting into focus; the cheerleader parts of “It’s a Beautiful Day”; the skating rink at the mall vibe of “Arigato We Love You” whose title ranks among my favourite song titles (an awful vibe for the most part, but I dig it here)—but the late-90s airport production stifles them, making everything sound soulless. They ‘expand their horizons’ by giving the drums more space in the mix, going so far as to play around with drum-n-bass textures which seems neat at first but only contributes to that clinical sound. i.e. Why am I listening to Pizzicato Five for drum-n-bass? i.e. Why do the heavy drums throughout “My Baby Portable Player Sound” sound so pasted in, and not charmingly so? A lot of these songs aren’t worth more than a few listens if that including the three short tracks early on, as well as “Collision and Improvisation” (nice textures but grows old quick) and “Porno 3003” (the first time I ever felt like the language barrier existed with these cats because it’s a 10-minute monologue without the benefit of nice textures).

That said, those textures are sorely missing on their next album, Playboy & Playgirl (1999), dispensing of any leftover drum ‘n’ bass after “Rolls Royce.” Consider this where they lose what made them special: the melodies aren’t as strong, and chords seem to drag into one another where once they used to bound into the next. “Magic Twin Candle Tale” is a weird one, featuring a murmuring male vocal almost the entire way through even though the song is about two lovers meeting in the night (“Baby Love Child,” this is not; this is a good song despite those additional vocals); “Concerto” has lively chamber orchestration that makes me think of the Toys “A Lover’s Concerto,” a connection I think I’d make even if it wasn’t named as such; “I Hear a Symphony” has that wonderful moment where the bass-line revs up and leads us into the backing male vocals; “Drinking Wine” has a lovely harmonizing saxophone, even if the mix is a little too close to sleepy R&B mall music; “Stars” features drums that pop like fireworks. Surprisingly, I consider the title track among the weaker ones here: it makes so much space for a hook that isn’t worth repeating.

On the surface, The Fifth Release from Matador (2000) should be a knock-out (it’s the fifth release because there was two compilations before Happy End of the World): the mix is more Bossanova 2001 than it is Happy End of the World although the drums do have more storm and bluster still. But the ratios are all wrong: too much honey in the singing and the strings which give the impression that there’s more melody when there isn’t. More tune, maybe? Not necessarily good ones if so: the one-note ‘la-la-la’ of “Wild Strawberries” wasn’t worth recording, let alone repeating. Not helping is that every song doesn’t seem to end even though the exit ramp arrives early on: “Room Service” effectively ends at the 3:19 mark, where they present a collage of static and samples, and then we get to hear that chorus one more time; “Goodbye Baby and Amen” deploys a piano glissando way too early when typically it would signify one final coda and then it spins its wheels for another 4 minutes. Even the ridiculous “Roma” should have been half the length instead of 3 minutes (and even then it’s the shortest song here).

“Goodbye Baby and Amen” would have made for a nice wave goodbye, but one more album came the following year, Çà et là du Japon (2001), which doesn’t even feel like a Pizzicato Five album given the minimal involvement of Maki Nomiya (notably, it wasn’t released by Matador either). Without Nomiya, Konishi outsources the majority of the vocals to various guests, mostly Japanese but Sparks is tapped for highlight “Kimono.” You could say Konishi’s heart wasn’t in it either considering how many covers there are, including one of “Gatta Call'em All!” which lists out all the Gen-1 Pokémon and features children singing the chorus.

Worth pointing out is that there was a cynicism in This Year’s Girl that is sorely missing in the records that came after, a cynicism that led to a distinct atmosphere abandoned for bubblegum pop. For example, the song “Let’s Be Adult” has a title that seems akin to, say, the Beach Boys’ “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” considering their love for the California band, but it begins by admonishing childhood fantasy and promptly lambasts adulthood after the chorus, while “Baby Love Child” has that moment that goes “Attention, adults…”, turning the love song into a proto-trip-hop song that makes me genuinely wonder if Geoff Barrow heard this in ‘91.

Most prominently, “Ohayo”—my favourite P5 song—sees Nomiya going about her daily routine, “コーヒーを淹れて / ラジオをつける” (translated as “Brewing coffee / Turn on the radio”), which promptly queues a detailed news report of an FDA agent gunning down an unarmed man running away, and then back to the lovely and busy morning as if nothing happened, criticizing or simply just pointing to how the majority of people consume the news. That album has hooks for days, sure. Ohayo, ohayo, ohayo, ohayo, ohayo, mm mm. Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you. Etc. But there was something deeply unsettling there. A key lyric: “世界の終わりさえ 気付かないかもね” —> “You may not even notice the end of the world.”