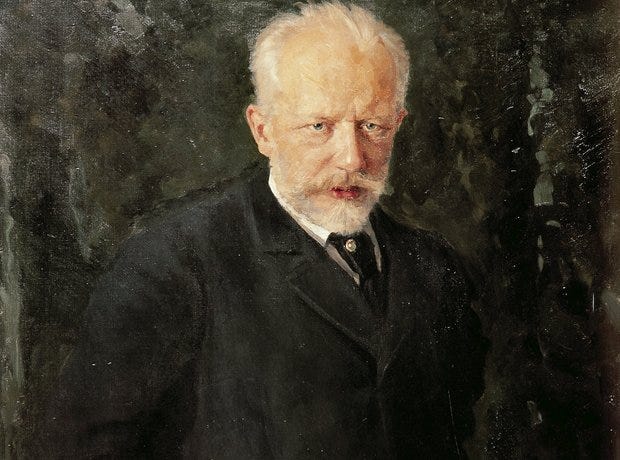

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Bring Me Chocolate Coffee or Tea

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky wrote a lot of music. “I literally cannot live without working, because as soon as some project has been completed and I want to indulge in rest, instead of rest […] there spring up anguish, depression, thoughts about the vanity of all worldly things, fear for the future, fruitless regret for the irretrievable past, agonizing questions about the sense of earthly existence […] and as a result there arises the desire to embark on a new project at once,” he once wrote, which explains why he kept leaping from new composition to composition. That, and his crippling self-esteem, which led to repurposing pre-existing works into new ones.

His body of work was also enabled by his very interesting friendship with Nadezhda von Meck, widow to one of Russia’s first railroad magnates, who paid Tchaikovsky 6,000 rubies a year (by comparison, working for the government as a minor official would net you 300-400), a person whom he had only met once on accident. In other words, Tchaikovsky is proof of what incredible things one can create when not encumbered by the anxieties of money! (Meck is also associated with Claude Debussy, who wanted to marry one of her daughters.) And so we received three ballets, seven symphonies (including the unnumbered one), operas, concerti, and tons of onesies besides.

What makes Tchaikovsky divisive is that he’s a melody composer, and melody is no longer seen as ‘cool’; he’s a ringtone composer if there was ever such a thing (him and Vivaldi). That, and Tchaikovsky’s music was very romantic: these melodies were maudlin (swooning) or bombastic (booming), in ways that would make a listener flush, intentionally or not. By contrast, Igor Stravinsky oozes cool to modern audiences, another Russian composer whose best work was also his three ballets.

As someone who loves the symphonic form, Tchaikovsky was clumsy and awkward there: I’d rank him below just about all the major symphonic composers (including Stravinsky, underrated on that front), but above, say, Robert Schumann. He wrote more symphonies than Liszt, but big deal: the first 10 minutes of the Faust Symphony is more compelling than any movement of any Tchaikovsky symphony. The way Tchaikovsky wrote symphonies felt like he would compose the basic architecture and then pad his way to the (usually) bombastic finish. Hence tons of clumsy transitions as he navigates from point A to point B. You see c-list rappers doing this a lot, where it feels like they wrote a line, looked up a possible rhyme on rhymezone.com to see what would fit, and then forced something in the next line to make it work.

What’s interesting to me is that Tchaikovsky was very likely homosexual, a fact that the Russian culture minister has vehemently denied (even though president Putin basically shrugged and agreed that the was probably gay) but is plain for all to see in the composer’s preserved writing (“My God, what an angelic creature and how I long to be his slave, his plaything, his property,” he once wrote about a servant). I feel like I’ve heard complaints about classical music being dominated by cis-white men my entire life as a means of not engaging with it, and yet, the composer with the single most popular work that’s performed year-round for tons of adoring families, was gay! A possible way to read (read: listen to) Tchaikovsky’s pieces is through the lens of his repressed homosexuality, aided by a marked turn from triumphalism to resignation in his late symphonies and perhaps why he gravitated towards adapting writing about unrequited love (Romeo & Juliet) and depression (Manfred).

Born in 1840, he did his best work around his mid-thirties; between 1874 and ‘76, he composed Piano Concerto #1, Swan Lake, Symphony #3, and Marche slave, a hugely productive period by any metric, and where I think he really started to come into his own. (I am not a fan of his pieces composed prior to that period.) Here’s a quick guide of the essentials, in rough chronological order, with some words adapted from my review of his symphonies on RYM.

Symphony #1 (1866), subtitled 'Winter Daydreams,' is far more interesting than the first symphonies of Schubert or Schumann (the latter of which was even more a clumsy an orchestrator and symphonic composer than Tchaikovsky). Tom Service’s article on The Guardian for the symphony as one of the 50 Greatest Symphonies (absolutely not) argues that Tchaikovsky had the impossible task of merging conflicting nationalism versus internationalism which did make me appreciate it more. Early in his career, Tchaikovsky was self-tasked to make Russian music accessible to a wider audience by incorporating Western practices, which was at odds with the Five’s school of thought, a group of prominent Russian composers who felt that Russian music should remain Russian. Hence the very western European chord progressions and even brief use of counterpoint in the first and last movements, a technique that he’ll use far less of overtime. Also of note is that the first two movements have subtitles (“Daydreams on a winter journey” and “Land of gloom, land of mists”), like he was constructing a symphony out of tone poems, which actually makes the composition more awkward if anything; like he didn’t trust listeners to arrive at the same visual conclusions. Frankly, I just don't hear the rich melodicism or sobering emotion in the slow movement as I will in Tchaikovsky's later works; the title of “Land of gloom, land of mists” is really unearned.

Romeo & Juliet (1869) remains popular to this day because of the melody that arrives about halfway through (it’s used to soundtrack when two Sims kiss, among plenty of other uses in media), but what I fondly remember the overture-fantasy most is the ascending harp chords around the 1:30 mark-onwards that proves that Tchaikovsky wasn’t just interested in tune, he was also about that texture. (Would “Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy” be as wonderful if it were played on a piano instead of a celeste? Take it from someone who’s heard Martha Argerich’s two-piano rendition, the answer’s no.)

In contrast to his first, Symphony #2 (1872) was much more Russian, subtitled 'Little Russia' after Ukraine since it draws on Uranian folk music. Predictably, it received the approval of the Russian Five where the first failed to do so. The finale is emblematic of Tchaikovsky’s bombastic tendencies: it starts big, and then gets bigger and bigger as it gets faster and faster in a stifling way.

There’s a lot going on over The Tempest (1873)’s 25 minutes, whereupon Tchaikovsky is trying to cover key parts of Shakespeare’s play including the actual tempest, Caliban, and the love story between Ferdinand and Miranda with the lovely melody that the piece eventually arrives at. Tchaikovsky later said of the piece, “The effect of these disconnected episodes produces a lack of movement and coherency.” A symphony with actual transitions might have let it stand on its own.

Symphony #3 is similarly very Russian despite being popularly referred to now as 'Polish' for reasons that I think even Tchaikovsky wouldn’t understand. Composed in 1875, a year before Swan Lake, the third is anomalous among his symphonies for being the only one in a major key and separated into five movements as opposed to four. Note the playful call-and-response in the fourth movement, around the 3:30 mark, between dramatic horns and quietly plucked strings.

Piano Concerto No. 1 (1875) is famous for its opening measures: Bahm-Bahm-Bahm-Bahm!!!-DUN!-Bahm-Bahm-Bahm-Bahm!!!-DUN! but it’s not particularly memorable besides. In fact, I’d say the first movement loses the plot relatively early: Tchaikovsky quiets every down at the 2:30 mark and then introduces a string swirl that feels like a big leaf has been pulled back and you’re looking at some gorgeous view, but the piano is far too clanging during this section: a weird mix of pastoral and modern that I doubt was deliberate.

Marche slave (1876) is one of Tchaikovsky’s most famous war pieces, written for wounded Serbian soldiers who fought against the Ottoman Empire, hence the brooding introduction that eventually goes full-out battle mode around 3 minutes in before the triumphant conclusion.

Swan Lake (1876) is the first of Tchaikovsky’s ballets, and so there’s plenty of symphonic drama abound, appropriate for a romance-tragedy where the main lovers die at the end. The ballet’s famous theme that arrives at the end of the first act sounds like it belongs in Star Wars to me, announcing the arrival of the Emperor.

Violin Concerto in D Major (1878) is far superior than his other concerti. It’s the best thing Tchaikovsky ever wrote that wasn’t a ballet. There’s a moment in the first movement that I look forward to every time, a bursting forth of great tuneage set to the deep pounding of the tympani lending it a stately and militaristic feel. And because the melodies always poured out of this man, this melody only lasts two repetitions across four measures (about 10 seconds) before he moves on. This happens just before the 9-minute mark of most recordings (which is coincidentally when the big moment of Romeo and Juliet happens too), but the preceding minutes are worth hearing to see how Tchaikovsky arrives at the release. Which is typically not the case for him as he often had issues linking one idea to the next. By contrast, the transitions in first movement of his Violin Concerto all work well such that the movement feels like one big crescendo to that moment: even when we get a taste of that melody early on in a different key, it doesn’t feel like the full release quite yet. That said, I check out around 17 minutes in where it becomes clear there’s nowhere left to go and Tchaikovsky just wants to keep going. The same is true of the third movement. Thus, the movement that works best front-to-end is actually the second one, which gets downright dreamy in parts.

Symphony #4 (1878) is modelled after Beethoven’s fifth symphony, a Herculean task that Tchaikovsky failed at. (Just compare the dramatic opening measures, and the overall structure.) The opening horn motif is an update of his first attempt at a big fate motif on early work Fatum with its huge-but-lumbering theme, which he destroyed after being criticized. It’s around this symphony-onwards that his transitions are composed with a little more care. Or should I say composed at all.

I’d say Piano Concerto No. 2 (1880) is better that the first even if it doesn’t have as strong an introduction or even melodic part, but there’s more of a piano presence from someone who usually hated the way the piano sounded in an orchestra, and I feel that’s the way it should be on a piano concerto. The pre-climax of the first movement cribs Franz Liszt’s “La Campanella” from three decades earlier (trilling at the highest point of the piano for an extended duration).

Leonard Bernstein famously referred to Manfred Symphony (1885) as ‘trash,’ but I don’t see it as that different from Tchaikovsky’s earlier symphonies although this one is long, doesn’t sustain interest, and is fairly atypical for Tchaikovsky in that we don’t have as much melody beyond the wedding organ in the finale movement. Both Schumann and Tchaikovsky were drawn to Lord Byron’s poem of the same name, and it makes sense: both composers were no strangers to mental anguish, and Byron’s Manfred came during a very hard time in his life, when Byron was cast into exile after a scandalous incestuous affair with his half-sister came to light. Mental anguish that comes from fucking your half-sister is still mental anguish! “My slumbers - if I slumber - are not sleep, / But a continuance of enduring thought.” Final word: Schumann’s overture is better than Tchaikovsky’s symphony.

There’s a resignation on Symphony #5 (1888) that’s been hitherto unexplored by Tchaikovsky, and his scratched notes about his own symphony (“Murmurs, laments, doubts, reproaches against [REDACTED]”) has led some to believe this one (and the following sixth) are coded feelings about his homosexuality. You’ll remember the melodies. Especially the sombre, opening one played by two clarinets—Tchaikovsky always liked the sound of two clarinets playing the same notes because it provided a fuller sound than just one—against the backdrop of dramatic strings. Love how the melody climbs, just to die back down. And then climbs again. And then dies. And you'll definitely remember the incredibly rich horn melody of the andante. Note the second theme of the fourth symphony, starting with a little call and response between the clarinet and the bassoon, and then delicate transition afterwards—holding its breath with only a few strings dipping in and out—back to a new, slinky clarinet line. I really love that clarinet line because it sounds so cat-and-mouse like; as soon as its line ends, a flute or a clarinet answers, only higher! (Or a bassoon, but lower!)

1812 Overture (1880) is famous for its conclusion (missed opportunity to not call it ‘Canon With Cannons’), which remains rousing despite all of its overplay to me on the very rare occasion that I choose to hear it (like Sibelius’ Finlandia, these are both pieces that are tied to such a specific nationalistic moment that I feel excluded from and the popularity of both eludes me). Tchaikovsky’s famously derided the piece as “Very loud and noisy and completely without artistic merit, obviously written without warmth or love,” but I demur: that introduction is one of his tenderest moments, and sounds like it came from a completely different piece than where it eventually ends up.

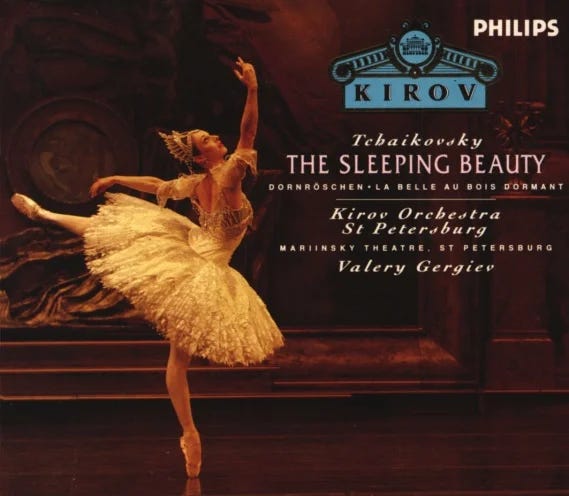

Sleeping Beauty (1889) is the longest of Tchaikovsky’s three ballets. By way of comparison, Gergiev’s performance of The Nutcracker fits on one disc, and Swan Lake fits on two, but The Sleeping Beauty requires three. Purely from a purely narrative perspective, I’d say it concludes at the end of Act 2 (the end of the second disc): the third act is a big dance party celebrating the end of the previous act. You know what happens: the prince kisses the girl, she wakes up; let’s dance. Musically, I’ll say this much: the whirling, violent theme that Tchaikovsky wrote for Carabosse is one of Tchaikovsky’s best bombasts (and that’s how the ballet opens), and “Pas d’action” is one of Tchaikovsky’s best swoons.

The Nutcracker (1892) is the best thing Tchaikovsky ever wrote, and it sounds like a better ‘best of’ compilation than most any best of compilation I know or could curate myself. Note the four national pieces in the middle (improving on the same from Swan Lake), and how they actually sound like the countries they’re honouring (with the Spanish percussion on “Chocolate” or the tea-kettle-whistle-melody of “Tea”), and that the one on “Russia” appropriately sounds far more vivacious than the preceding three. (Compare these pieces to Philip Glass’ pieces on China, Africa, and India on Powaqqatsi where they all sounded far too similar. That was a limitation of Glass: he always sounded like New York.)

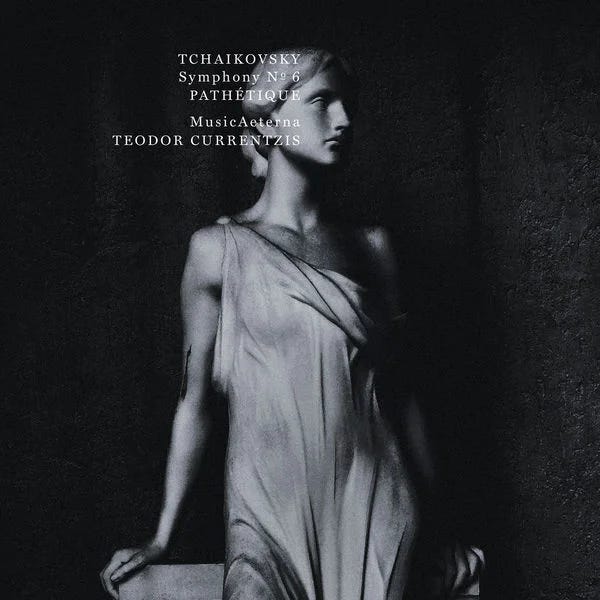

Symphony #6 was his last-major composition, written in 1893. Posthumously and now popularly referred to as 'Pathetique', the closest English translation to what his brother dubbed Патетическая (“Patetitčeskaja”) is actually 'passionate,' and what an excellent word to describe Tchaikovsky! So many overblown finales! Not on this one however. After toying a little with form and tradition on his previous symphonies, he finally just flips the table: no more clumsy, overbearingly bombastic climaxes. He resigns instead: the finale is 12 minutes of some of his most solemn melodies; the horns moving from mourning to dread. His sixth symphony is the only one that would rank among Tchaikovsky’s top five pieces, and even then, it only gets fifth place.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention “Berceuse” (1893), introduced to me on Theremin where it’s the best piece, the belated debut album from Clara Rockmore who helped popularize the non-traditional, non-physical instrument when she was forced to switch over to it after malnutrition-caused tendonitis prevented her from playing the violin.