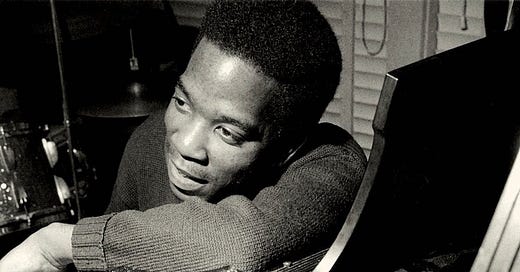

Conrad Yeatis “Sonny” Clark passed away on January 13, 1963 from a heroin overdose. He was thirty-one years old.

It was not his first overdose. He almost died in September 1961, and the sounds of him on the verge of death and a friend trying to keep him alive were serendipitously captured by photographer W. Eugene Smith who had rigged his apartment building full of microphones to capture daily life and accidentally caught all of it on tape. Clark survived, and was immediately back behind the keyboards as Blue Note’s de fact in-house pianist. One month after that, he was a sideman for Jackie McLean’s A Fickle Sonance. The month after that, he recorded Leapin’ and Lopin’, his last album. And in December of 1961, he recorded Blue & Sentimental for Ike Quebec. If his addiction to heroin was slowing down his input or impacting his performance, it didn’t show. Case-in-point: in August of 1962, Dexter Gordon remarked that it seemed like Sonny Clark had “almost totally given up” but the music that came out of those recordings, which yielded two albums under Gordon’s leadership in three days, were the best albums of Gordon’s career, in part because of Clark.

Born in Herminie, a coal-mining town just a stone’s throw away from Pittsburgh, Sonny Clark passed away just as hard bop was moving away from its formulaic structure of theme-solos-theme and towards the freedom of post-bop, which might have impacted his legacy; he came from a linage of Bud Powell and Horace Silver; put crudely, Clark coloured within the lines, whereas Thelonious Monk drew his own lines.

Besides Bill Evans and John Zorn—who formed the one-time Sonny Clark Memorial Quartet to tribute the pianist on the 1986 album Voodoo (not as good as Clark deserved, but still appreciate Zorn for doing it when no one else was)—most of the interest for Clark in the decades that followed came from Japan, where Blue Note reissued Clark’s discography and released posthumous sessions that would not be widely available in America until much later. (Notably, Japanese pianist Ryo Fukui covered Clark on his 1994 live and last album.) While researching Clark, I found this cool statistic from Sam Stephenson via The Paris Review: between 1991 and 2009, “Clark’s 1958 Blue Note recording, Cool Struttin’, sold 38,000 copies in America and 179,000 in Japan […] John Coltrane’s classic 1957 Blue Note recording, Blue Train, sold 545,000 copies in America over the same period and 147,000 copies in Japan. Cool Struttin’ outsells Blue Train in Japan.”

Because he died so young, his discography is compact, and I can’t think of many jazz discographies that are so short and yet so intensely rewarding. (Here’s another if you’re looking for Blue Note pianists with short careers: Herbie Nichols.)

Here’s the guide:

If you go by recording date, then 1957 was a huge year for Clark as he recorded his first three albums; if you go by release date, then Clark dominated 1958 just behind Miles Davis with three great albums. Dial “S” for Sonny is good, but it pales in comparison to what came after, and maybe that’s to do with the rhythm section Wilbur Ware on bass and Louis Hayes on drums never pushing the band; Hayes should have been poking at the soloists far more on the title track, which is a good one nonetheless with its laid-back melodic charm.

Sonny’s Crib is better by leaps and lopes. The rhythm section of Dial “S” are replaced by the far more dependable Art Taylor on drums and Paul Chambers on bass; Curtis Fuller remains, and joined on the frontlines are Donald Byrd on trumpet and John Coltrane on saxophone, recorded two weeks before Coltrane went into the studio to record Blue Train. Byrd and Coltrane set “With a Song in My Heart” ablaze, navigating the brisk tempo with ease. “Speak Low” might be even better, where Clark interprets the standard with the slightest of a Latin touch. There’s a physicality to these songs that just wasn’t there on the previous album. The blues-inspired second half doesn’t produce any songs as good as these, though Coltrane rips his way through his solo on the title track.

Perhaps noticing that the wealth of horns was burying Clark, he recorded Sonny Clark Trio, blazing his way through a set of six standards with his best rhythm section yet in Chambers again and Philly Joe Jones on drums. “Shoutin’ on a Riff” from his debut was fast, but “Be-Bop” and “Two Bass Hit” are performed at an Olympian level, and Clark’s staccato melody at the 2 minute mark is catlike and never fails to perk a smile on my face. It wasn’t just at high speeds that Clark shone though: he performs the closer “I’ll Remember April” by himself in one of the best solo piano jazz songs that I can name; the bluesy touch reminds me of Jaki Byard who hadn’t yet emerged on the scene. I wish that Clark made more trio records, but perhaps he figured that format was overcooked.

Cool Struttin’ keeps the same rhythm section but re-adds Art Farmer from Clark’s debut and Jackie McLean. Key to its success is its poster-ready cover—one of the decade’s most iconic—and the title. Clark had already proven time and time again he could dazzle, he could sear, but not before the title track did he write one that actually strutted. Whereas Clark was buried by the other soloists on Sonny’s Crib, his solos on the Latin-infused “Blue Minor” and Miles Davis-written “Sippin’ at Bells”—first recorded by Charlie Parker—are some of his absolute best. The chords skipping down the stairs at 7:35 of “Blue Minor”? The tornado swirl at 1:35 of “Sippin’ at Bells?” Phenomenal stuff; cat-like in precision and playfulness. “Bells” ends with a bowed solo from Chambers, and then “Deep Night” begins with a feint, starting as a trio cut—a reminder that his debut ended with a trio song—before bringing back McLean and Farmer as a surprise. A point of comparison: Chet Baker also tapped Miles Davis’ rhythm section that same year on In New York, but Cool Struttin’ is a really special album whereas In New York is surprisingly good, not great. (Heroin also claimed Baker’s life.)

Featuring a completely different line-up consisting of Butch Warren on bass, Billy Higgins on drums, Charlie Rouse on tenor saxophone, and Tommy Turpentine (brother of Stanley) on trumpet, Leapin’ and Lopin’ would be Sonny Clark’s last album released in his lifetime, and his only album recorded in the new decade. The theme of “Somethin’ Special”—one of Clark’s originals here, and one of his should-be standards—enthusiastically bounds off the record after the needle drops. “Voodoo” is his other compositional highlight, featuring a witchy bass-line and circular melody that earns its title. Perhaps too strung out to write much else, he has Turpentine and Warren write one each. Both are relatively simple. Turpentine contributes “Melody for C,” a simple—just that—melody that bounces between two chords that Rouse solos over phenomenally. Warren’s “Eric Walks” bursts forth appropriately for the second side opener, but isn’t memorable besides.

That’s his core discography. There was one album for Time called Sonny Clark Trio (not to be confused with the Blue Note one) with George Duvivier on bass and Max Roach on drums, but the recording quality leaves a little to be desired. The best songs on there can be found fleshed out in another version on the posthumous albums that Blue Note released in Japan in the late-70s, all cobbled together from recordings in the late-50s when Clark was at his peak, though none of them are essential. The Sonny Clark Quintets combines the results of two different bands (hence the name ‘Quintets’), and its second half would have been interesting if guitarist Kenny Burrell were given more to do. The first half of the album, “Royal Flush” and “Lover” were from the sessions that yielded Cool Struttin’, and the latter has a really awkward attempt to change time signatures that doesn’t come off — not helping that the waltz itself sounds like generic music box material. Sonny Clark recorded some standards with Wes Landers and Paul Chambers at the end of 1958, packaged up as Blues in the Night, that are strangely amateur-hour, especially in comparison to Sonny Clark Trio: it’s a laid back collection that could have been made by anyone. My Conception should be more noteworthy since it’s Clark recording with Art Blakey behind the kit, and you’d think the two would be a match in heaven since some of Clark’s hardest hard bop felt ready for The Big Beat backing him. But Blakey isn’t bringing the thunder: “Junja” could’ve used a little more muscle, and I’m not a fan of how sometimes Blakey treats ballads as an excuse for naptime with regards to the title track.

The best song on his final album, Leapin’ & Lopin’, is the sole standard, “Deep in a Dream,” where special guest Ike Quebec steps in after Clark’s solo with a tenor saxophone solo that’s lush, beautiful, and sentimental without ever getting boring or mopey. It should have been the closer of the record. A year later, Clark passed away from an overdose, and Ike Quebec died from lung cancer just three days after him.

Dial "S" for Sonny - B Sonny's Crib - A- Sonny Clark Trio - A- Cool Struttin' - A Sonny Clark Trio - B Leapin' and Lopin' - A- The Sonny Clark Quintets - B Blues in the Night - C My Conception - B

Great stuff!