What really defines the Band for me is how much emotion each member put into every single note. And I’m not even talking about the pain in the various voices (obviously that too), but every instrumental feels—for lack of a better term—weighty. In the intros of “The Weight” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” alone, it feels like an entire world has been collapsing on this one person’s shoulder, such that when the rest of the band comes in, it feels like they’re trying to rally one another. Because of that, there is something truly brotherly about the Band, so much so that I cannot imagine any other band around this time deserving of a name like theirs, even though they merely kept their original name from their tenure as Bob Dylan and The Band. Speaking of, has there been another case of backing band turned renowned superstars?

Regardless that I only count two great studio albums, two good studio albums, one great live album and the material they cut with Bob Dylan, I declare them the greatest Canadian band and feel no shiver of doubt there. (Change the word to ‘artist’ and they’ll get bronze behind Joni Mitchell and Neil Young.) When I look up lists of best Canadian bands and see Rush or the Tragically Hip, I get filled with overwhelming dread. And seeing flavor-of-the-year indie favourites like Alvvays, Arcade Fire, Broken Social Scene, Destroyer, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, and Japandroids does not make me feel any better about the situation that is Canadian Music In General, especially when some of these bands have wrote themselves out of the conversation.

When Robbie Robertson passed away on August 9, 2023, the first thing I thought of was how smoldering he looked in The Last Waltz (pictured below; Canadian hotness peaked in 1976), and then how I vastly underappreciated him as a guitarist. I once quipped that it was good that Neil Young didn’t bring the electric axe at that concert because it would’ve highlighted the disparity between the two, but that wasn’t fair to Robertson. Robertson was minimal, sure, but his fills were precise, soulful, and exactly what the songs required of him. His sting at the 0:23 mark of the Waltz’s version of “The Night They Drove All Dixie Down” is one of my favourite single seconds in guitar music, and his introduction to “The Weight” is an all-timer precisely because it is so unassuming. Robertson doesn’t even get five full seconds before Levon Helm comes in with his drums, but in those few moments, he manages to zip around, declare himself and—crucially—make you feel ‘the weight’ that the band go on to sing about. Compare what Robertson does here with the swampy intro from the Allman Brothers’ Duane Allman leading Aretha Franklin’s cover. Even with additional time and a louder tone from an electric, Allman can’t pull off a statement like Robertson’s intro here. It’s like Beethoven vs. Brahms between the two.

The Band originally got their start as the Hawks, backing rockabilly starter Ronnie Hawkins, and eventually graduated to Bob Dylan’s backing band when he went electric. Later in 1967, they rehearsed together with Dylan in the basement of a house they dubbed the ‘Big Pink’ (because it was pink on the outside). The results of which have been disseminated to Dylan-lovers in waves: one of the first-ever rock bootleg in 1969, and then The Basement Tapes in 1975, and then The Bootleg Series Vol. 11: The Basement Tapes Complete in 2014.

A handful of songs released on The Basement Tapes don’t actually feature Dylan at all and only feature the Band. Some were recorded around that time and subsequently overdubbed by Robbie Robertson for their official release, while the recording dates of others are in dispute, with some thought to be recorded in 1975 and not 1967. The four-part harmonies of “Ain’t No More Cane” predict the glorious harmonies soon to come on the proper Band albums, and “Orange Juice Blues (Blues for Breakfast)” is more heavily blues-influenced than anything else the Band would ever do. Manuel’s soulful swings on that one (“I’m on my way out the do-or”) are just delightful; he was the Band’s best vocalist in those early years. Sure, as the first track states outright, some of it is actually ‘Odds and Ends’; “Katie’s Been Gone,” with its simple rhythm for example, sounds like a warm-up of better ballads to come. But ultimately, The Basement Tapes is a treasure trove of basement-psychedelia that I just can’t get enough of; in a Desert Island scenario and forced to choose between the two Dylan albums released in 1975 (this and Blood on the Tracks), I know my answer, even if it’s not the better ‘album.’

The six-disc complete set released almost four decades later doesn’t bother with Robertson’s overdubs, with Toronto producers Jan Haust and Peter J. Moore restoring the tapes to their original conditions to the best of their abilities, and then arranging them in rough chronological order. Some of it sounds like shit; there’s tape hiss everywhere, there are songs where nothing was microphoned properly for Haust and Moore to salvage (“Jelly Bean”); takes that end on a dime; vocals are sometimes out of sync or out of tune or simply out of earshot of the microphone stand (“She'll be Coming Round the Mountain”). But I am simply endeared to hear Bob Dylan do a lighthearted take on a Hank Williams classic, or the Band’s backing vocals on “Silent Weekend.” Do yourselves a favour and take 30 seconds out of your day to hear “See You Later Allen Ginsberg” which sounds like it was recorded simply because Bob Dylan figured out ‘Allen Ginsberg’ shares phonetic similarities with the word ‘alligator.’

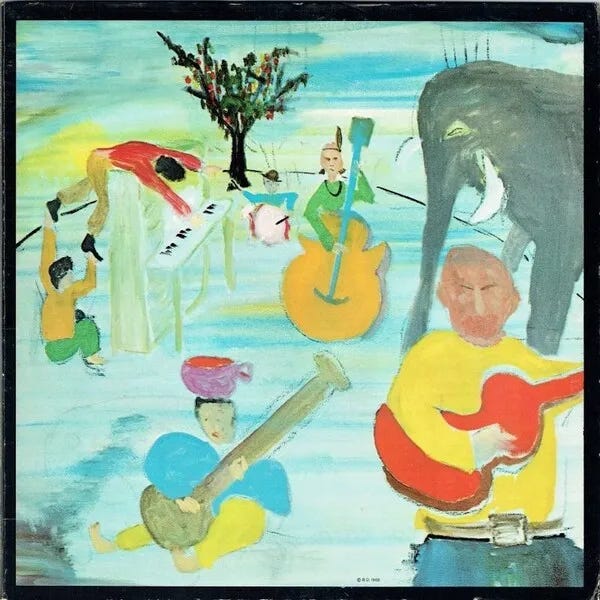

In 1968, Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail considered Kensington Market’s Avenue Road “probably the finest album ever cut by a Canadian group.” Alas, the internet is scant with information about the forgotten Kensington Market, and so I cannot confirm Avenue Road’s exact date of release, but either (a) The Globe should have waited until Canada’s Day that year where they would have received the Band’s Music From Big Pink, the actual-best album cut by a Canadian artist by that point in time until it was usurped by Neil Young in May 1969 and then the Band themselves again in September 1969, or (b) The Globe was dead wrong. Either way!

What’s really interesting is that for a rock album—for one that is often considered a highlight of Canadian rock music—the guitar plays such a small role. There’s that 4-second intro of “The Weight” that I mentioned, and the rippin’ solo of “To Kingdom Come,” but for the most part, the guitar is used for gritty texture and is no louder than Richard Manuel’s piano, while Garth Hudson’s organ might actually be louder.

It’s mad-man Hudson that elevates this band beyond mere ‘roots rock’ or ‘country soul’ or ‘folk rock’ or any other reductionist tag. He begins “Chest Fever” by quoting Bach and then proceeds to go in a completely different direction, the buzz of the organ blistering through the speakers and the chords themselves splintering away. That intro deserves mention as one of the hardest rockin’ segments of the album despite no other instruments. Meanwhile, Hudson’s intro on “This Wheel’s On Fire” uses a similar trick to Robertson’s intro on “The Weight” in how they both hit a high note and linger there, and just how memorable both intros are despite how short they were.

Songs like “The Weight” and “We Can Talk” demonstrate their kinship with one another, specifically the glorious harmonies on the former (aided by Hudson’s colourful keyboard climb), and the way Richard Manuel, Levon Helm, and Rick Danko play off each other on the latter, “Well, did ya ever milk a cow? (Milk a cow?)” Ultimately, Music From Big Pink was a short-lived snapshot of a democratic band: Robbie Robertson writes the most songs here, sure, but there are also assists from Manuel and Danko, both of whom completely stopped contributing as the years went on.

The Band is even better. “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” is the classic, empathizing with the Confederate soldiers after the American Civil War with a tender vocal from Levon Helm (“We were hungry, just barely alive”). Helm’s supple, powerful, and yet somehow still understated drum-work on that song is genius; each new drum pattern or drum-roll is a seismic current that pushes the song to its next line or the next chorus, and what a rousing chorus it is! Helm was really the beating heart of the band; the only member of the Band that was not Canadian, he brought American blues and history that he acquired growing up in Arkansas into the Band’s sound and lyrics. For example, the band covered “Ain’t No More Cane,” a prison work song he learned from his father while growing up in Arkansas on The Basement Tapes, and “The W.S. Walcott Medicine Show” is based on Helm’s memories of medicine shows in Arkansas.

But every song is good. Given the songcraft and talent involved, there’s not a single piece of filler even when the album loosens up in the second half by comparison to its stacked first side. The absurdity of “Jawbone” (“I’m a thief and I dig it! / I’m on a reef, I’m gonna rig it!”); Manuel’s soulful vocals on “Whispering Pines”; the swampy bass of “Up On Cripple Creek”; the irresistible fiddle of “Rag Mama Rag”; how “Look Out Cleveland” looks backwards to their time as the Hawks for inspiration and then proves how far they’ve come. And there’s the outstanding delivery by Manuel that opens the album, “Standing by your window in pain,” followed by the ‘response’ of those electric guitar chords. You wouldn’t expect it from that opening alone, but soon the song switches into optimism and invites you to journey across the great divide yourself (“just take that ride”). One of many basically-perfect albums released in 1969 (along with The Beatles, Miles Davis, Neil Young, the Rolling Stones, Sly & the Family Stone, and the Velvet Underground), but it’s also the one that pairs best with an old fashioned cocktail.

Consider Stage Fright the decline. A fine entry, and even good in parts, but it’s hard to listen to and not be disappointed compared to their previous two albums. Others have put it more succinctly than I can, so I’ll defer to them. Elizabeth Nelson, via Pitchfork, “Stage Fright, a charming, loose-limbed collection that elides the chore of living up to the previous records by basically not even trying”; Greil Marcus on Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ’n’ Roll Music, “Stage Fright was an album of doubt, guilt, disenchantment, and false optimism […] The Music at its best was still special, but in every sense, the kind of unity that had given force to those first two albums, and to the idea of the Band itself, was missing.”

I lay a lot of the blame on Robbie Robertson, who once again writes the bulk of the material but I think the issues mostly lie on mixer-engineer Todd Rundgren, who I do not think was the correct person for this kind of job. On songs like “Strawberry Wine,” “Time to Kill” and, especially, “The W.S. Walcott Medicine Show,” the Band are grooving to the point of funk music, but Rundgren is unable to cook the mix to emphasize that, and what we end up is slightly (stilted if) danceable roots rock. Or, just compare “The Shape I'm In” here to the searing version from The Last Waltz.

Not helping is that—similar to Bob Dylan's New Morning (a better album than most people realize; “If Not For You,” “Day of the Locusts” and “Winterlude” are sublime, and the album is better than The Times They Are A-Changin’ for starters)—there's that early-70s low-stakes feeling of contentment, whereas before, they were disillusioned but willing to pull through. As a result, there’s no classic song here. Only “The W.S. Walcott Medicine Show” might make a top ten Band songs. And even on that song, the invocation of the Ku Klux Klan wouldn't have been just a random throwaway line on a previous album.

There are plenty of electrifying moments: the instrumental section of “Daniel and the Sacred Harp” between Rick Danko’s fiddle, Robertson’s autoharp, and his pedal steel guitar; Levon Helm’s tippy-tappy drumming on “Time to Kill”; old producer John Simon’s low swinging trombone on “The W.S. Walcott Medicine Show” and Garth Hudson’s impressive saxophone solo on that same song; when the chords change so Richard Manuel can sing the title’s words on “Just Another Whistle Stop.” But therein lies the issue as well: I remember moments more than full songs.

On February 2021, the 50th anniversary edition was released—never mind that the release date would be almost 51 years later—and presented a different track-list using all ten original songs that vastly improved the flow of the album. Moving “The W.S. Walcott Medicine Show” to the opener is the logical move; not only does it groove more than “Strawberry Wine,” but it has a clean hook too. But another important move was moving “Sleeping” from the second track to the closer where it belongs: “Sleeping” is one of two songs where Manuel has a co-write and ranks among the ballads of their previous album, with Manuel's piano selling the image of ‘turning from the sun and seeing everyone searching,’ and in lieu of any actual chorus, the song picks up its feet for every other verse or so, but it has no business being placed where it was on the original setlist. In an interview with The Globe and Mail, Robertson revealed that he only put those two songs there “to be encouraging of [the other bandmembers’] songwriting, so I put them at the top of the album,” but the re-arranged track-list which shoves them to the back “restore[s] the original Stage Fright experience.”

Cahoots suffers the same issues. Increased use of heroin stopped Manuel from contributing any songs, leaving Robertson to bear essentially all of it with the exceptions of opener “Life is a Carnival” (co-written with the rest of the band sans Manuel), “4% Pantomime” (co-written with Van Morrison), and “When I Paint My Masterpiece” (donated by Bob Dylan). These are, without fail, the album’s best songs: the Bob Dylan one has the cleanest melody, and Manuel adds some lovely marimba during the bridge to make it feel like you’re sailing away in that ‘dirty gondola.’ “Life is a Carnival” sounds unlike anything the Band has cut before thanks to Allen Toussaint’s horn arrangements, looking forward to the incorporation of horns on live album Rock of Ages recorded later that year. Morrison sounds like he’s having fun with the nonsense rhymes of “4% Pantomime,” inspiring Manuel in turn.

But the other songs are spark-less, limping slowly towards the piano fills of “Thinkin’ Out Loud” or the blustery sections of “Volcano.” Bob Clearmountain was given permission from Robbie Robertson to more liberally edit the album for its 50th anniversary edition, removing instruments or even reworking parts of the album to breathe new life into the mix. “Shootout in Chinatown” is most notably changed, the riff sounding far more modern and also highlighting the eastern scales (which Greil Marcus originally described as “Fu Manchu guitar, a touch so tasteless it verged on racism”), but it doesn’t sound like 1971 to me. It sounds artificial, death for a band so invested in tradition as were the Band, and frankly, I miss those warm percussion tones in the original anyway.

With Robertson creatively exhausted, the Band retreated, first with a covers album in Moondog Matinee, returning to their roots as the Hawks by covering some rockabilly and trying their best with “A Change Is Gonna Come.” And then by reuniting with Bob Dylan as his backing band on Dylan’s Planet Waves. Planet Waves is Dylan’s first proper album in three and a half years since New Morning, ignoring the soundtrack Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid and outtakes compilation Dylan, and it’s simply not good enough. Like Another Side of Bob Dylan, it’s a sentimental album of personal love songs openly addressing his then-wife Sara Dylan, but it’s far less multifaceted than Another Side of Bob Dylan from a decade prior which was, by turns, sardonic and seething and never this sappy. Robbie Robertson’s guitar on “Going, Going, Gone” is a happy reminder of the Robertson we used to see, but “On a Night Like This” pales in comparison to the Band’s hootenannies from only five years ago. It does, of course, have “Forever Young,” one of a handful of Dylan’s classic songs that I only need to hear once every few years to get my fill of.

Bob Dylan and the Band toured together, and the recordings were compiled on Before the Flood. The album’s title comes from a line on Planet Waves, which is not represented at all in the setlist, which only serves to highlight how disappointing Bob Dylan’s song selection on The Last Waltz would be: it’s like a hit parade! The album is not as good as critics made it out to be when it first landed as Dylan’s first live album (Xgau: “When [Dylan] sounded thin on Planet Waves, so did [the Band]. Now his voice settles in at a rich bellow, running over his old songs like a truck”); the Band’s arrangements sometimes sound fussy, particularly Hudson’s prog rock organ. But Robbie Robertson sounds incredible throughout (including channeling Hendrix for “All Along the Watchtower”), clearly more comfortable playing old songs (or someone else’s songs) than writing and playing his own new songs.

And so, having taken several years off from writing, Robertson was recharged and so composed the entirety of Northern Lights — Southern Cross on his own. Were it not for this album, then the Band’s best studio output would be limited to only two years, pretty paltry for a classic rock band. But Northern Lights — Southern Cross is their third-best album and the only studio album of interest after 1970’s Stage Fright. Garth Hudson plays synths, a potentially frightening prospect, but the synths are just an extension of what he was exploring on the organ, used as tasteful texture. Robertson experiments by playing clavinet on “Jupiter Hollow,” a demonstration of what the Band’s sound could be had they soldiered on, and by using a 24-track tape recorder, it allowed them to overdub keyboards on top of one another. The album is a little too mid-tempo, a feeling that’s doubled by the fact that the song lengths are longer on average (despite there being only 8 songs, it’s actually 5 minutes longer than Stage Fright), but “Ophelia” (a stronger image of New Orleans than “Life is a Carnival”) and “Acadian Driftwood” are the Band’s last great studio songs.

The reason why The Last Waltz is better than Rock of Ages is much more superficial than you think and it has nothing to do with the expansive setlist or the bevy of important guests or the Scorsese-directed film. Of course, those things help, but at the end of the day, for me, it boils down to the fact that The Last Waltz simply sounds better. Fuller. Bigger. Brighter. Better.

There are different stakes contextualizing these two albums. Rock of Ages sounds like it’s trying to re-ignite themselves after their then-most mediocre entry Cahoots. Are there comparable stakes on The Last Waltz? Yes, but of a different kind. Recorded in 1976, the Band—and Bob Dylan, and Joni Mitchell, and Neil Young, and Eric Clapton—are no longer at the height of their powers (okay, Emmylou Harris’ voice never ages and Muddy Waters is at a second high here), but in some cases, well into their declines. As such, there’s a real ‘goodbye to rock’ feeling that I get listening to The Last Waltz that just isn’t there on Rock of Ages, partially because it would be the last time the Band performed together as the band we all know and love, yes, but also because it was released close to the end of (let’s not get too dramatic here) The Last Great Decade of Classic Rock Music.

A negative: I can’t help but be disappointed in the song selections from my heroes. Joni Mitchell is knee-deep into her anti-pop phase, and so refuses to acknowledge her career pre-1975, even if this version of “Coyote” may trump the original which I already adored (how she seethes when she imagines the man smelling her off his fingers while eyeing other women). Neil Young doesn’t bring the electric axe and hint at Rust Never Sleeps. And Dylan, well, half of his songs are from Planet Waves whereas they didn’t bother for Before the Flood, and it’s the other half—from way back in his past—that interests me the most, “Baby Let Me Follow You Down,” performed like an early Kinks song, and “I Don't Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met),” turned into a electric scorcher compared to its acoustic version.

As for the actual Band songs, well, put it this way: Rock the Ages-The Last Waltz is simply not a combo worthy of The Name of This Band is Talking Heads-Stop Making Sense, the obvious ‘two entirely different worthy live albums by the same group, one of which is also a film’ comparison. The Band do spice up the arrangements on both those live albums with horn arrangements (although the horn arrangement was much more inventive on “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” even if this version is better overall, and that one segued perfectly into “Across the Great Divide” which is sorely missing here), and they give it their all in the actual performances (Levon Helm getting really into it in the final few seconds of “Up On Cripple Creek”), but there’s not enough major re-arrangements which is a large pull for me for live albums, which is not the case for those Talking Heads albums.

Unlike LCD Soundsystem, who similarly threw on a big farewell concert (that clearly wanted to be like their own Waltz) but then put out a new single in less than five years later, The Last Waltz was recorded in 1976 and the next time the Band released new music (not counting the contractual obligation that was the b-side compilation Islands) was seventeen years later. And even then, it was not the same version of the Band. Robbie Robertson had embarked on his solo career, and had creative disagreements with the rest of the bandmembers anyway: The Last Waltz was his idea that he thrust upon the band, and there was bad blood between Levon Helm and Robertson about songwriting credits. Meanwhile, Richard Manuel, who suffered substance abuse for years, hung himself in 1986.

The three albums the Band put out in the 1990s feature some old recordings of Manuel where they had them, but no contributions from Robertson, relying instead on lots of covers (including a far too happy reading of Bruce Springsteen’s “Atlantic City”; “Well, now, everything dies, baby, that's a fact / But maybe everything that dies someday comes back” was not to be read optimistically). These albums are irrelevant to their career, and not very good.

The pull of the Band in those first few years were that they were equals; that no one’s voice was more important than anyone else’s, which gradually became less and less true as they became a less democratic and increasingly fractured band. During those early years, they were just four Canadians and one American trying to get to the heart of this weird, strange splotch of land south of them. And more than most any actually-American band of their era, they succeeded in doing just that.