Wayne Shorter

Orbits

I. Introduction

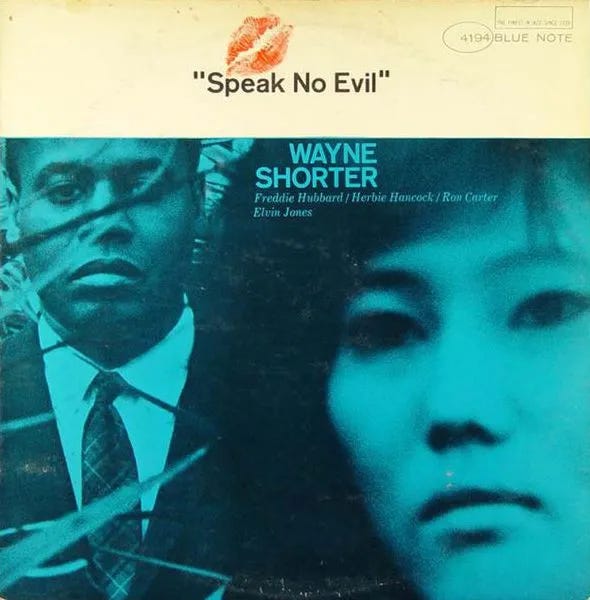

“Wayne Shorter, at this moment, is the greatest living small-group jazz composer, which might not sound like much of a distinction-or at least a less flashy one than, say, greatest tenor saxophone. But it means a great deal, because in the 1950s and 1960s jazz was full of players who could write fantastically memorable lines, and now there are very, very few.” Ben Ratliff wrote that in his entry of Wayne Shorter’s Speak No Evil in Essential Library Jazz: A Critic’s Guide to the 100 Most Important Recordings (2002), and even two decades later, I’d say that holds true.

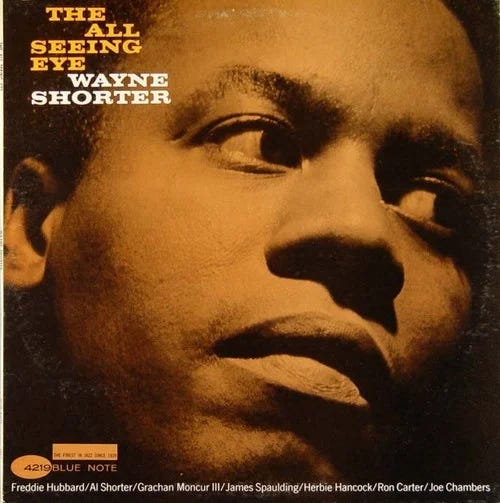

Before embarking on this deep dive in his discography, I was familiar with only a handful (6) of his 23 albums as a bandleader, having already determined that Speak No Evil and The All Seeing Eye were the bee’s knees and having already fallen in love with him because of the thirteen songs he wrote as part of Miles Davis’ Second Great Quintet before Davis went fusion across those four key albums from E.S.P. to Nefertiti, not counting Water Babies. “E.S.P.,” “Nefertiti” and “Paraphernalia” are their respective albums’ best songs, and both Sorcerer and especially Miles Smiles owe a lot to Shorter.

After listening to all of his studio albums, I can’t help but feel a little…disappointed? His best albums are those two. His run was short, not helped by Blue Note doing that thing where they sat on two of the albums to space out the releases, and not as special as the run by the aforementioned Second Great Quintet (the timelines do overlap to his credit), or say, Dexter Gordon’s run also on Blue Note before he moved to Europe. And then, you know, Shorter got sucked into fusion after playing on In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew, started Weather Report and never looked back (basically) even though his audiences kept hoping he would.

I think it’s harder to write about Wayne Shorter than his contemporary tenor saxophone colossuses because you can’t decouple his improvisations, his innovations or his compositions from one another: they’re so intertwined. As a composer, Shorter wrote a book of bop songs, tore up the pages and created the rulebook of post-bop. Shorter’s melodies aren’t just little tunes. Tunes are easy; they’re beneath him. Shorter’s melodies are tomes, passages winding around and around, glancing the distance up ahead, and then travelling that distance in the ensuing improvisation. Questions are asked, answered, rephrased and then re-asked, and he does this at impressive speeds and with harmonies aplenty too. Shorter was an avant-garde that was separate from the actual avant-garde at the time by being out there juuuuuuuust enough not to push anyone away while also asking you to listen harder.

Don’t take it from me. Ask anyone who’s played with him. Freddie Hubbard: “A lot of people don’t know that Wayne’s one of the best writers that we got on the jazz scene. I did some of his best records, Speak No Evil and The All Seeing Eye, but I had to take that music home and practice it. I played with all these guys, with Sonny and Trane, the heavy guys, but Wayne wrote the strangest songs, the ones that got you.” Miles Davis: “Wayne also brought in a kind of curiosity about working with musical rules. If they didn't work, then he broke them, but with musical sense; he understood that freedom in music was the ability to know the rules in order to bend them to your own satisfaction and taste.”

In Michelle Mercer’s Footprints: The Life and Works of Wayne Shorter (a great read, especially about Shorter’s tenure with Miles Davis, although too much time was spent convincing you of his works post-75), Mercer details at length how Miles Davis’ respect for Wayne Shorter knew no bounds: he begged Shorter to join his band, he returned the rights to “E.S.P.” to Shorter (originally credited to both of them) which was unheard of for Davis, he paid Shorter for missed gigs with no questions asked. She also makes the point that Shorter was the only one from the Second Great Quintet to make the original transition to electric: Ron Carter was replaced by Dave Holland, Herbie Hancock by Chick Corea, Tony Williams left when he caught wind that Miles Davis wanted to experiment adding an extra set of arms. Shorter looked at the changing of the guard, shrugged, and changed from the tenor to the soprano saxophone so he could be heard above the din. It was just music to him at the end of the day.

A jazz legend who was active for six decades now and counting (sort of), Wayne Shorter ultimately had a relatively medium-sized discography if you don’t include his work as Weather Report, which I won’t cover here.

II. The Early, Early Years

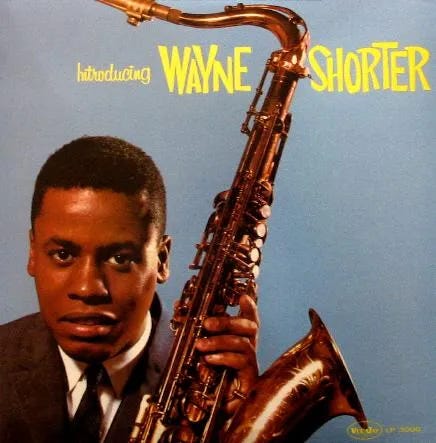

In the same year that Wayne Shorter joined Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers (1959), he recorded his debut album for Vee Jay in two days which was released the following year. Debut album Introducing Wayne Shorter (1960) does exactly what the title promises, introduce both sides of Shorter, that is, the saxophonist and composer (five of the six songs here are Shorter originals). Fellow Jazz Messenger Lee Morgan is also here, and both Shorter and Morgan get the best solos in because curiously, pianist Wynton Kelly is lost in the mix; you really have to strain to hear his contributions during Paul Chambers’ solo on “Blues a la Carte. ” And when Jimmy Cobb really pushes Kelly during Kelly’s solo on “Mack the Knife” with that metronome-like smack, no blazing tempo can amount for the fact that the volume ain’t hard enough for this kind of hard bop. “Down in the Depths” runs over 10 minutes (on a debut album no less) points to Shorter’s ambitions later on but it isn’t anything particularly special; ditto the easy-going “Pug Nose” right after.

Second Genesis (recorded 1960, released 1974), recorded in a single day shortly after the release of Wayne Shorter’s debut, would have been Shorter’s second album had Vee Jay not released it 14 years later. That said, the material is very, very slight. Credit where credit is due: the sound has more edge to it, but that is solely because Art Blakey is here on drums instead of Jimmy Cobb. The intro to “Ruby & the Pearl” is pure Blakey brilliance, starting off with atmospheric washes of cymbals giving way to the evening lightning that we all automatically associate with Blakey, and it makes the song worth more than anything from Introducing. But a huge negative is that Lee Morgan isn’t here anymore, replaced by…no one. Songs are shorter because it’s only Shorter and Cedar Walton on keys doing the improvisation, which lends the record’s eight songs an ‘interchangeable’ feeling with one another. A larger role from Blakey could have solved this, but Blakey isn’t the type to steal the show from a musician he’s backing.

Thus, Wayning Moments (1962) would be the best of Shorter’s three albums for Vee Jay by course-correcting the issues of both Introducing Wayne Shorter (by miking pianist Eddie Higgins better) and Second Genesis (by bringing in Freddie Hubbard as a foil). Marginally, anyway. Shorter is still playing it far too safe, and of course, Hubbard isn’t exactly known for pushing himself too much (even though Hubbard’s played on more than a few out-there records for others). Rhythm section Jymie Merritt on bass and Marshall Thompson on drums do exactly what they’re asked for and little more; Art Blakey is missed. Songs are short once more in the vein of Second Genesis but given that Shorter is sharing time with Hubbard, this means that the solos tend to be shorter still, and thus, more forgettable; Hubbard’s solo on the title track bursts with energy in the climax and is promptly cut for Higgins, who doesn’t do anything special. “Powder Keg” does earn its title but it’s empty bluster, and Shorter gets to test the waters with balladry on the following “All Or Nothing At All” that he’ll soon master. None of these three records are essential.

III. The Blue Note Run

Between 1964 and 1969, Blue Note released six Wayne Shorter albums for public consumption which form an ‘arc’: Shorter finding his niche (Night Dreamer, Juju), perfecting his craft (Speak No Evil), diving deeper into the avant-garde (The All-Seeing Eye) and then emerging on the other side (Adam’s Apple, Schizophrenia). Here’s my PSA: Blue Note fucked up when they sat on The Soothsayer and Etcetera for fifteen years (releasing them when Weather Report was big to generate more income I guess): The Soothsayer is a stronger album than exactly four of those six albums, recorded at Shorter’s peak in 1965 and experimenting more with strange, mysterious harmonies while being the missing link between Speak No Evil and The All-Seeing Eye.

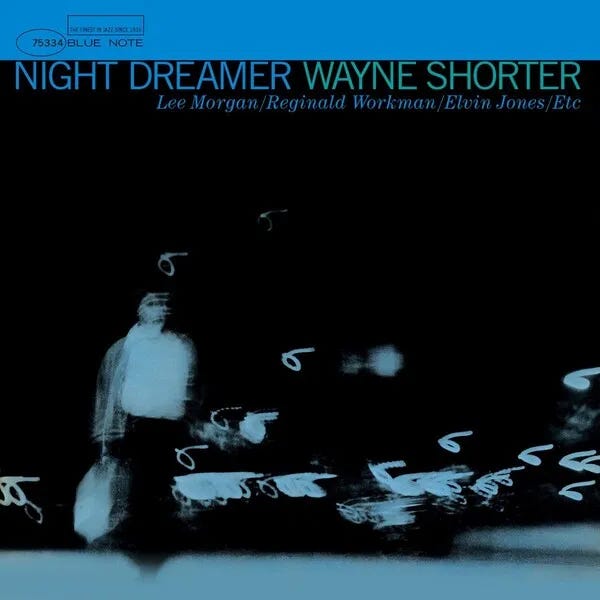

Night Dreamer (1964)—a title I associate to Miles Davis’ ‘Round About Midnight; both debut albums on new labels that show their respective bandleaders’ predilection for the night (I’d say Night Dreamer takes the edge over ‘Round About Midnight)—sees Shorter and Morgan working together again, finally, with John Colrtane’s band: Reginald Workman (before he was replaced by Jimmy Garrison), McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones. (Worth pointing out is that the cover clearly has enough space to credit all musicians involved but buries McCoy Tyner as ‘Etc’ because of label contracts but it’s hard to think of something more disrespectful.) The first few seconds distinguishes Night Dreamer from Shorter’s previous records on Vee Jay: the sound is crisper, and the compositions allow far more complex improvisations while retaining supple, supple melodies. Tyner’s introduction to “Night Dreamer” is one for the ages, your last thoughts before sweet sleep and deep dreams. “Virgo” is a precursor to Speak No Evil’s “Infant Eyes”; Tyner’s chords continuously spiraling upwards to heaven, which he actually breaches during his solo. Jones keeps the fire going on the second side, which cools off a little bit in quality by comparison.

Juju (1965) features the same band as Night Dreamer minus Lee Morgan, so you’d think this would be weaker by default. But it’s not! It’s strangely better. Without Morgan, Shorter makes clear that he’s the anti-Coltrane while working with Coltrane’s band, forming a tight axis with McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones. (Reggie Workman seems forgotten about in the RVG Edition.) “Deluge” is one of Wayne Shorter’s greatest compositions: one of those indelible melodies that I talked about, but making it particularly special are Tyner poking his head in like a cat (his glissando makes a guttural “Meeeeeow!” sound) and Jones’ peek-a-boo drumming. Shorter’s solo on “Yes or No” really take the theme’s ‘both directions at once’ seriously, his little melodic fragment at the 2:47 - 2:55 feels like the ‘yes’ voice trying to goad the ‘no’ voice along, and when that fails, they lay down the a staccato melody that you simply can’t just say no to.

Speak No Evil (1966) replaces Coltrane players McCoy Tyner and Reginald Workman with other members of Miles Davis’ second great quintet, moving even further away from Coltrane where once people noted their similarities. Whereas Coltrane was getting louder and louder, Shorter was getting quieter and quieter while still retaining a healthy appetite of what he could do with jazz. There's a lot of rule breaking here; this ain't your grandma's post-bop/hard bop: unexpected harmonies make up the chords of "Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum," unexpected blats from Freddie Hubbard in the same song play like Wayne Shorter were conducting this quintet as if it were a big band. And, of course, this album contains Shorter’s best-ever song in “Infant Eyes” (his tribute to his newborn daughter). Note the gentle snowflakes of Herbie Hancock's intro, pianissimo (very soft) arcing into a piano (soft) at the 0:12 mark and landing even more gently than how it began. And then Shorter takes over, with nothing but pure grace in tone and tune. “Infant Eyes” reminds me of Robert Schumann's “Träumerei,” from the Kinderszenen set, compositions that were meant to convey childlike wonder and innocence. White clouds, green pastures, running ahead and looking back to see your mother smiling at you.

The Soothsayer (recorded 1965, released 1979) and Etcetera (recorded 1965, released 1980) are the two archival releases that should have been released after Speak No Evil as they were recorded before The All Seeing Eye if all was right in the world. The Soothsayer is notable for featuring a take on Jean Sibelius’ “Valse Triste” sporting a Latin-inspired rhythm courtesy of Tony Williams: I don’t count it as a highlight, because even though Shorter was clearly interested in forms beyond American jazz (“Oriental Song,” “Juju,” “House of Jade,” “Indian Song”), he wasn’t as invested as, say, Charles Mingus, and these all just come off as another bop song, and not like “Valse Triste” was a particularly special song to begin with. (“Juju” has a mini-repetition that’s supposed to sound like an African chant; “House of Jade” only has a few measures that sound east Asian, the bridge that Shorter wrote into his wife Teruko Nakagami’s piano intro. And frankly speaking, “Oriental Song” doesn’t sound oriental to me at all. Good solos though! The best of these songs is “Indian Song” from Etcetera by a fair margin.) Instead, I’d sooner point you to the ballad “Lady Day” (which starts with the same note from Shorter as “Valse Triste”) or “The Big Push” (featuring one of the coolest solos from Freddie Hubbard, ever), while “Angola” is another catchy winner for Shorter.

The All Seeing Eye (1966) is his most overtly 'out there' album through more muscle and musical attempts at recreating Genesis (the Bible, not the band) and depicting Mephistopheles that I swear are inspired by Hungarian mad-man composer Franz Liszt (i.e. the intro to “Genesis”; the very fact that the devil is saved for last like the Faust Symphony). Shorter’s quintet is expanded into a septet here not including older brother Alan Shorter’s appearance on “Mephistopheles”: fellow Miles Davis quintet members Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter are joined by James Spaulding, Freddie Hubbard, Joe Chambers and Grachan Moncur III. “Genesis” plays a neat trick by shifting in structure very much like something from Charles Mingus’ The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady before eventually actually finding a groove near the middle. Sonically then, “Genesis” is Shorter trying to mirror God’s creation of Earth: from formlessness comes form. “Chaos” sounds very much like what Shorter was writing for Miles Davis around this time (but with more horns), which is to say, fuck yeah! One negative: Hubbard sounds lost sometimes, as he does on Ascension (much as I like him, Hubbard was too much of a straight-shooter to be playing on such avant-garde records) and it occasionally makes me wonder how Lee Morgan would’ve handled these horn solos.

Adam’s Apple (1967) is a somewhat disappointing retreat, returning to the quartet format of Juju after his most ambitious offering. Most notably, this album contains the first-recorded version of “Footprints,” which would become one of Shorter’s most famous compositions when the first-released version on Miles Smiles came out half a year before. That 5-note bass-line’s an ear-worm no matter the context, but I simply prefer the dark stew that rhythm section Tony Williams and Ron Carter cooked up to Joe Chambers and Reggie Workman’s less spicy simmer here. So I lean towards some of the other cuts: the delicious groove of “Adam’s Apple” (compare to “Backlash” by Freddie Hubbard around the same time and it’s clear who was the far stronger composer and improviser); Herbie Hancock’s harmonies during Shorter’s solo from 1:48 - 2:00 on “502 Blues”; the insane barrage from Hancock and then Joe Chambers’ toms-heavy solo on “Chief Crazy Horse.”

Schizophrenia (1969) finishes Shorter’s 60s’ run with more disappointment. Has there been a mental illness—any illness—more grotesquely misrepresented to the public than schizophrenia? And yet, when a musician in the 60s uses the mental illness to frame their album, replete with an album cover depicting a mirror image of themselves, then you kind of get the idea: two different personalities. Because of this framing, I have always been disappointed with Schizophrenia because it doesn't go deep enough into Shorter's two different 'modes' of traditionalism and avant-gardism. Instead, it's firmly rooted in the middle, i.e. more post-bop of Adam’s Apple. Some critics may allege that Schizophrenia sounded more 'out there', and thus, more dangerous (not to feed in to the misrepresentation that schizophrenia = dangerous) to listeners back in '69 when it was released. Well, I disagree: all of these songs scream mid-60s to me.

IV. Middle Period

On the one hand, distilling Bitches Brew into a brisk 38 minutes sounds like it ought to be more appealing but the truth is, it also removes what made Bitches Brew so appealing in the first place, which is how impregnable that album seems. (Seems. Get Up With It is much more impregnable; dense.) Super Nova (1970) was recorded almost immediately after Bitches Brew was completed, and Shorter took with him a lot of the same players: Chick Corea, Jack DeJohnette, Airto Moreira and John McLaughlin, combining them with future-Weather Report bassist Miroslav Vitouš and two other guitarists in Walter Booker and Sonny Sharrock. (John McLaughlin channels In a Silent Way on “Water Babies” by sounding very much like a keyboard.) Some weird decisions here, like not letting Sonny Sharrock or John McLaughlin solo; keyboardist Chick Corea plays drums again which he was playing more during his time with Miles Davis. As such, the spotlight is completely centered on Wayne Shorter who is in full-out John Coltrane mode, much more than he has ever been before. His solos are long and occasionally cacophonous, in search of a spiritual release without ever once kowtowing to how pleasing the sound may or may not be. And yet: too fusion-y to be spiritual jazz and definitely not fused with enough rock or funk to qualify as fusion.

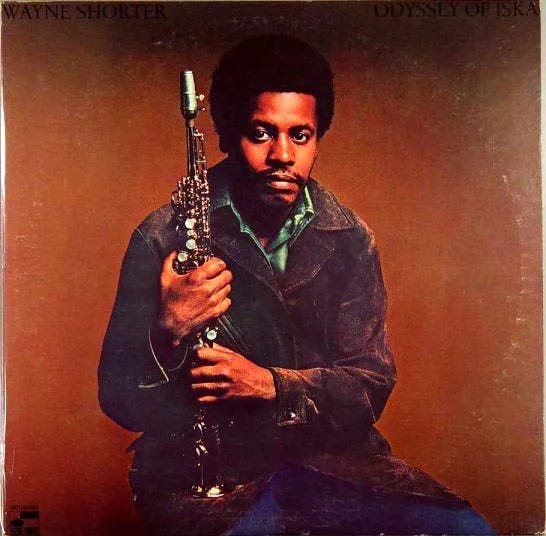

Shorter’s second daughter Iska suffered an allergy-related complication to a vaccination, and the result oxygen deprivation caused severe brain damage which would eventually lead to a grand mal seizure and Iska’s premature death. The grief-stricken Wayne Shorter wrote Odyssey of Iska (1971) for her, heard in the spiritual playing and seen in the titles. “Wind” (the word ‘Iska’ is Hausa for wind)” and “Storm” are followed by “Calm” and “Joy.” Shorter assembled a new band for Iska: guitarist Gene Bertoncini, bassists Ron Carter and Cecil McBee, drummers Billy Hart, Alphonse Mouzon and Frank Cuomo, and vibraphonist David Friedman. (Frank Cuomo’s other big contribution to music is that he fathered Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo, born just before recording this album. He played on no other albums.) All are Shorter originals except the bossa nova tune “Depois do Amor, o Vazio” by Shorter’s friend Bobby Thomas, a song that has a nice beat when it’s finally introduced and a great solo from Shorter that singlehandedly brings the song to a climax but is generally a little too easy-going and too long in the tooth. “Storm” is the highlight thanks to Bertoncini whose chicken-scratch funk guitar gives the song a groove while also making it seem nervous with energy, before proceeding to play with and against Shorter; you gotta dig underneath all that percussive energy to find David Friedman, but I’m glad he’s in there.

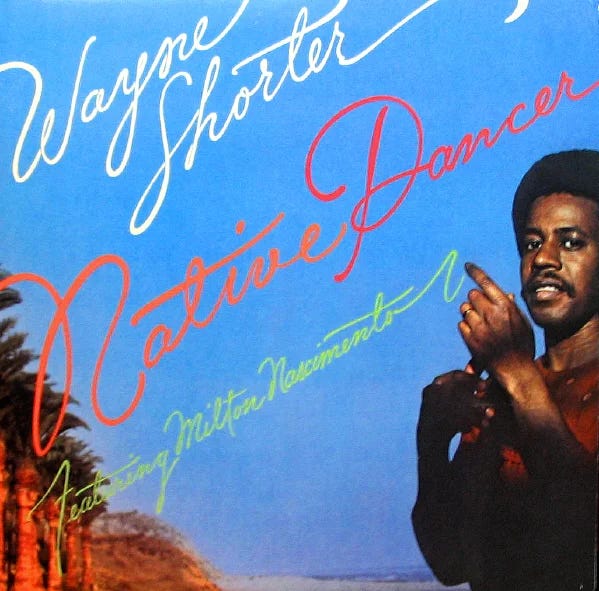

In the same day that they recorded Odyssey of Iska, Wayne Shorter also knocked out Moto Grosso Feio (recorded 1970, released 1974) with many of the same players so you would think the quality is about the same. Except most of the players must have went home and so the sound isn’t as ‘deep’; it’s actually far looser and ‘airier’ than the previous two albums, and not in a particularly atmospheric or enticing way. Only “Montezuma” and “Vera Cruz” work up much of a groove, the latter notable for being a Milton Nascimento cover, looking ahead to Shorter’s soon-to-come with the Brazilian musician.

It’s hard not to overrate Native Dancer (1975) a little, considering it’ll be the last good Wayne Shorter album for a while, considering it was released in the middle of Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock’s increasingly cheesy fusion period, a.k.a. the point of no return. At the same time, it’s also hard not to be disappointed that this album isn’t the jazz-MPB crossover hit that Getz / Gilberto was for jazz-samba almost a decade earlier, partially because Astrud Gilberto’s voice fit better on that album than Nascimento’s does on this album. To look at it another way, I wish Astrud Gilberto sang more on that album, whereas I sometimes wish Nascimento sang less here, especially when “From the Lonely Afternoons” feels like a retread of the opener. And without the task of trying to incorporate Nascimento, Herbie Hancock gets in a great solo reminiscent of his 60s’ work on closer “Joanna’s Theme.” Surprisingly, the electric instruments are used far more sparingly than you would think given that it’s 1975, and not only that, they put in work: Herbie Hancock can’t help himself play electric piano on at least one song when both Wayne Shorter and Wagner Tiso are playing them, and he makes “Tarde” warm and exquisite. But the main highlight is the opener, “Ponta de Areia,” featuring Milton Nascimento’s charming, soaring and unmistakable falsetto in full display, and then an incredibly touching solo from Wayne Shorter that at first doesn’t seem like it belongs in the same song but soon is led back in by Wagner Tiso’s electric piano chords.

V. Late Period

Wayne Shorter’s late period closely resembles that of his friend Joni Mitchell, whom he worked with from Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter all the way through to Both Sides Now. Both released three troubling albums in the 1980s. Both ‘course-corrected’ this in 1990s and won Grammys. And then basically did what they wanted for the rest of their careers, which was not much in either case:

There were no Wayne Shorter solo albums until Atlantis (1985), likely because Weather Report’s end was in sight and so he pivoted back to his solo career. Take one look at the year it was recorded/released and guess how it sounds. If ‘shit’ was your answer, you’re right although it’s not quite the nadir for Shorter yet. Basically, I don’t think 60s’ acoustic jazz musicians were meant to be anywhere near 80s’ pop production, and not helping is that Shorter is surrounded by nobodies here: pianists Yarón Gershovsky (who?) and Michiko Hill (who?) and keyboardist Joseph Vitarelli (who?); Hollywood flautist Jim Walker on one of his earliest dates (who?); Joni Mitchell producer-bassist-husband Larry Klein on electric bass (his sort of bass playing was exactly what Mitchell meant when she talked about putting up picket fences). Shorter sure plays a lot of notes, but none of them coalesce into a single melody and all of them are scoured of any emotion; there’s something oddly synthetic about this whole album even though almost everyone is playing acoustic instruments.

Phantom Navigator (1987) is his actual-worst album with baffling textures like the drum programming on “Mahogany Bird,” the person grunting in a way that harmonizes with Wayne Shorter’s saxophone on “Condition Red.” There's a different synth player and person doing drum programming on every song here. The title of “Forbidden, Plan-IT!” is one for the ages: unintentional comedy. Some people call Joy Ryder (1988) an improvement over Phantom Navigator but if you shuffled the tracks and played them for me, I’d gag no matter what so I say ‘who cares?’ The synth assault of “Joy Ryder” and the lurching groove of “Over Shadow Hill Way” just don’t invite you to hear what Shorter might do over them, and when Shorter solos, he’s playing too many notes without saying anything anyway. (Some sage advice from Miles Davis to Shorter during the Great Quintet days: “can you also not play everything?”) Old pal Herbie Hancock is featured here on two tracks, but not like that matters since Hancock hadn’t touched an acoustic or even electric keyboard in so long, and to no surprise he brought his synths, but Shorter didn’t think to write an actual song for Hancock on “Anthem” which is merciful in its relative short run-time but also just a black hole of filler anyway. The other track that Hancock plays on is closer “Someplace Called Where” where he harmonizes with a grating vocal performance from Dianne Reeves.

High Life (1995), Wayne Shorter’s first album on Verve, is better than these albums by default but we’re trading one evil for another: the sound is more pleasant, sure, but in that toothless contemporary 90s’ jazz way, and bassist Marcus Miller and Rachel Z’s synths box Shorter’s compositions/improvisations in. My recommendation is to skip straight to Alegria (2003) instead, which Mercer points out was his first purely acoustic studio recording since 1967.

Alegria reminds me of Sonny Rollins’ contemporary solid late-period album This Is What I Do in the sense that both have those cozy vibes when you meet up with an old friend for a drink. Adding to that effect is that Shorter revisits a few old songs here: a far slower, richer take of “Orbits” from Miles Davis’ Miles Smiles (originally a short, punchy and weird number that’s flipped inside out here, featuring one of Shorter’s most interesting solos ever although it sounds like he starts searching for something that isn’t there near the end) and “Angola” from The Soothsayer (originally a hard-driving jazz song that’s turned into a very seductive groove thanks to Alex Acuña). But this is not a nostalgia-fest. Every other song seems to be posited as proof that Shorter still has it, whether it’s slotting himself into Heitor Villa-Lobos’ “Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5” or proving that his compositional talents are still intact. In that regard, the two main highlights are opener “Sacajawea” and “Vendiendo Alegriía.” The former is brought to life by the playful dance of Danilo Perez’s keyboard and Brian Blade’s ever-shifting drums while “Vendiendo Alegría” is split into two parts, the first a moving ballad performed by Wayne Shorter backed by minor harmonies from a small horn section which proceed to get much livelier when the song assumes a Latin groove. (Alegria means ‘joy’ in Spanish, harkening back to the song “Joy” from Odyssey of Iska.)

Emanon (2018) got a lot of press for a jazz album, and it seemed like almost no one was willing to call out how overblown this gets. The first disc of new material simply doesn't sound good, and it's just another reminder of how most 'third stream' is usually just a bastard child of two disparate genres. There’s no body, and at the same time, the 34-piece orchestra swallows up the quartet instead of the colour-support the chamber instruments provided on the preceding Alegria. The live discs are actually the best part of the album, mining Emanon material, yes, but without the orchestra. (But my question there is that, aside from possibly "Orbits," are either of "She Moves Through the Air" or "Adventures Aboard the Golden Mean" fan-favourites? Why not play "Infant Eyes" or "Juju?") This also won the jazz Grammy, and of course it did: it’s one of the most meaningless awards.

VI. Extras

Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams and Ron Carter—The Second Great Quintet sans Miles Davis—linked up with Freddie Hubbard and formed V.S.O.P., which stood for the most eye-rolling of acronyms, Very Special One-Time Performance. They released Five Stars (1979) which was a big deal to hear all these fusion artists play acoustic instruments again, ‘cept they’re playing as if them as if it were fusion. (And you can’t fool me: that has to be an electric bass Ron Carter’s playing on “Skagly.”) Every member except Carter contributes to one of the four songs, with Tony Williams getting in a nice drum solo at the end of his “Mutants on the Beach” but Wayne Shorter’s unassuming “Circe” (not to be confused with “Circle,” which is a Miles Davis song written during the Wayne Shorter years) might be the album’s best even though it’s “Footprints”-lite.

Speaking of meaningless Grammy Awards, the same band but this time sans Freddie Hubbard would re-unite with a different trumpeter Wallace Roney and release A Tribute to Miles (1994). (Roney studied under Miles Davis between 1985-1991 and there’s a cute story where Miles Davis first met Roney and gave him one of his own trumpets upon hearing Roney didn’t have one.) It’s better than Five Stars although no one in their right mind would tell you that these versions of these songs are better than their originals, which, you know, had Miles Davis in the first place (i.e. no one would ever tell you to listen to this). Faithful versions of “Little One,” “Pinocchio” and “Eighty One” were nice to hear from (essentially) the same band, although speeding up “So What” feels like a crime and Tony Williams drops a barrage to introduce lovely miniature “R.J.” that feels inexplicable to me.

In Weather Bird: Jazz at the Dawn of Its Second Century, Gary Giddins considers 1+1 (1997), the collaborative album with only Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter, as “An album of absences, it has something to disappoint everyone. On the one hand, it is acoustic-soprano sax and piano-and highly melodic, with not even the echo of a funk backbeat. On the other, it is by no means a conventional jazz record, eschewing as it does blues, standard harmonic progressives, and swing. Its daunting sameness in tempo and mood can only be perversely deliberate, yet each piece is beautifully played and imaginatively conceived.” (Giddins manages to put a really positive spin on basically negative qualities (“daunting sameness”) about so many 90s’ albums that don’t stand up to the test of time.) Worth stating is that 1+1 follows Shorter working out unbelievable personal trauma when Ana Maria, his wife of thirty years, suddenly passed away when the TWA Flight 800 exploded into the Atlantic in 1996 en route to visiting Shorter on tour. Ana Maria’s death hangs over the songs: Shorter’s blowing near the end of “Meridianne - A Wood Sylph” is devastating while his partner evokes Erik Satie. Alas, too long, too long! And I can’t help but think that a bass and drum kit could only have turned “Aung San Suu Kyi” (which nabbed them a Grammy) into a Shorter all-timer; the melodic component is certainly there.

A lot of negativity on this page! There’s a brilliant line on Wayne Shorter by Gary Giddins on why Wayne Shorter didn’t look back by playing an entire-acoustic album for many years there: “My guess is that, like Sonny Rollins, he is one of those painfully honest musicians who can’t happily fake an orgasm or traverse old ground.” I don’t want to get into a debate of whether or not one should be faking orgasms to keep the other person happy (obviously not), but in this particular case, I know I would’ve been much happier. So to end on a positive, here’s Steely Dan’s “Aja,” which Wayne Shorter contributes a solo that brings the song to climax in such a way that makes me think of conquering a mountain. It surely ranks among one of the top 10 saxophone solos on a rock song, ever?