The great rap paradox: Wu-Tang Clan is the greatest hip-hop group if and only if you take into account the solo careers of its various members. Because from a sheer discography perspective for only the group albums, they have no claim to that title: Beastie Boys, De La Soul, Public Enemy, and A Tribe Called Quest—just to name groups that predate them—all have better discographies by virtue of releasing more than just one great album. I guess I just revealed my hot take early on: Wu only have one great album as a group, the first one. The acclaimed double sophomore album, I’d file under ‘I hate what this stands for but the rapping is good throughout.’ Well, except for Cappadonna anyway.

That said, from a sheer talent perspective, you can’t beat numbers like this because Wu-Tang Clan had a deeper roster than any of those groups mentioned above: nine rappers in its original iteration (before Cappadonna signed on). And what talent! Ghostface Killah arrived like the perfect mix of Rakim and Chuck D., and later evolved into the most talented storytellers in hip-hop, while Raekwon has a way of rhyming that no other rapper has figured out yet. Both rank among my top five rappers. Rappers donning nom de guerre’s is nothing new, but that Wu-Tang Clan were made up of so many alter-egos upon alter-egos—i.e. the Chef and Bobby Digital—made them feel like a genuine supergroup, and that they had different personalities—i.e. the Genius and the Bastard—made them feel like a rap version of the Avengers. This feeling was further emphasized when Ghostface Killah began leaning harder into his ‘Ironman’ (the lack of space makes me wince) persona, or that Robert Diggs considered RZA his favorite superhero in interviews. Even RZA, known best for his beat-making, is actually underrated as a rapper: he has at least a few verses that made me go ‘woah’ (whereas U-God and Cappadonna and Masta Killa have none).

What made Wu-Tang Clan more special than any other hip-hop group, however, wasn’t numbers—not least when some of their members are just there for the ride—it was their mythology. Hip-hop groups being violent (N.W.A.) or funny (A Tribe Called Quest) was nothing new, but Wu-Tang Clan tempered those two elements with a genuine love for kung-fu, and forged a unique identity for the group. Wu-Tang Clan’s music feels insular as a result with all the movie samples and Staten Island-specific references, but the world-building that they undertook from the get-go (“Shaolin shadowboxing and the Wu-Tang sword style”) made it so that you wanted to be a part of their world. Compare this to RZA’s other group, Gravediggaz (with Prince Paul), which had the violence and humor, but not the mythology (or the depth).

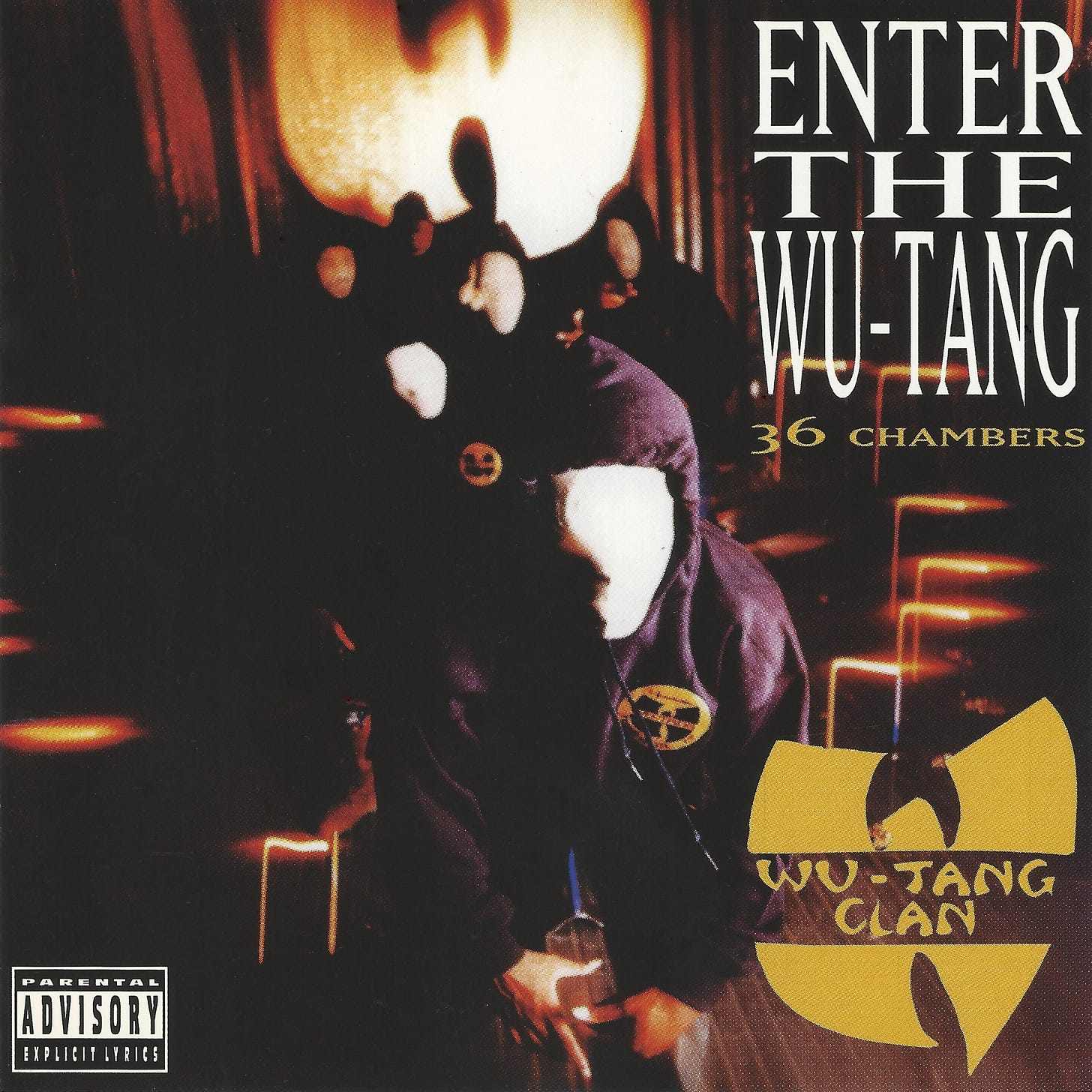

What made debut Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) more special than any other hip-hop album from its era is the brevity, something it shares with Illmatic. The album somehow introduces the group’s love for kung fu films, establishing the group’s mythology as well as the flows and personalities of its various rappers, and it does all that in just 12 songs under an hour. There’s no bullshit because there’s no room for bullshit; even the few skits rank as some of the best in the genre (“Put a hanger on a fuckin' stove and let that shit sit there for like a half hour, take it off and stick it in your ass slow like ‘tssssss’”).

A lesser group might’ve given each member a solo spot and wasted far too much time, but here, we only get one, and Method Man takes that rare opportunity seriously: if I only heard this album and none of their solo albums, I would’ve been convinced he was their best rapper, and their funniest to boot. Actually, I wonder if he still earns that spot for his inventive and fun rhyming on “Shame”: “Gunnin’, hummin’, comin’ at ya / First I’m gonna get ya, once I got ya, I gat ya” is my favorite couplet here. Ghostface Killah hasn’t quite figured out his style yet but he has figured out the inventive rhymes, and his entrance—“I come rough, tough like an elephant tusk / Your head rush, fly like Egyptian musk”—feels like a visceral roar worthy of Ice Cube. RZA’s sampling will never be on this level again, serving up two different samples of Thelonious Monk to make “Shame” constantly mutating across its under-3-minute run-time, while other beats sound woozy in a way that makes the rhyming feel like it’s coming from a smoked-out basement, especially the New Birth’s sample on “Clan in da Front.” Just those two songs, both coming in relatively early, made it feel like he was going to be a crate-digger on Prince Paul’s level, which turned out to be wistful thinking when he practically ditched sampling altogether. The bangers that bring da ruckus are all great, but ultimately, it’s the emotional songs—the Wendy Rene-sampling “Tearz” and “C.R.E.A.M”—that showed the group’s depth, something that they all but forget about as they moved forward.

(RZA’s last line on “Tearz” is “I wish I had a chance to sing these three words” and then he deploys the Wendy Rene sample which goes “After laughter comes tears,” which is, y’know, four words…)

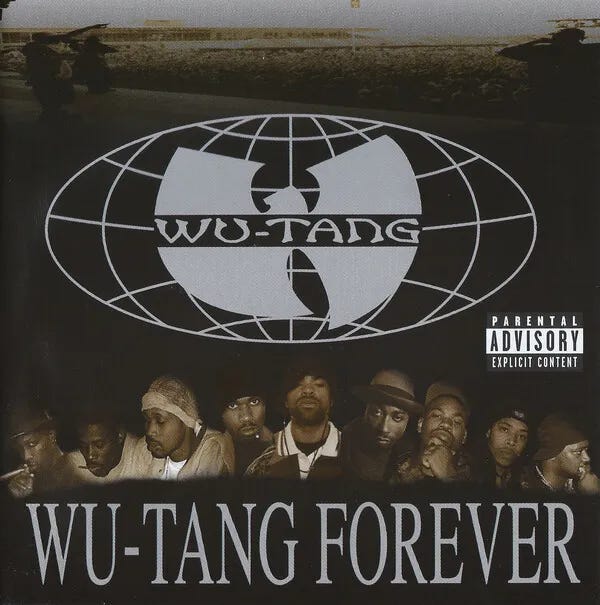

A lot of things happened between 1993 and 1997, namely the solo albums of Raekwon, Ghostface Killah, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, Method Man, and GZA/Genius, and a lot of things hadn’t didn’t happen, namely the solo albums of Inspectah Deck, Masta Killa, and U-God. Which is part of why there’s an audible rift on Wu-Tang Forever: by the time of the group’s second album, they already feel less like a group; no choruses where it sounds like all nine members are shouting together.

Between the years of 1993 through 1996, RZA held for the title of the best hip-hop producer, having taken the crown from Prince Paul after he stopped producing for De La Soul. And then he lost what made him special in the first place when he traded away the dark basement atmosphere for Hollywood (symbolically at first, and then literally when he started composing film scores). Like De La Soul’s Stakes is High, the beats on Wu-Tang Forever often feel like live instrumentation that’s simplistic (to bypass sample clearance issues and just the work needed to look for and procure samples in the first place).

With no samples or—“It’s Yourz” aside—hooks as catchy as the ones on their debut, Wu-Tang Forever feels like a rapper’s album, by which I mean one that you listen to solely for the rapping, where Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) functions great regardless if you zero in on the rapping or the beats. But it’s not even a good rapper’s album because of the sequencing: here’s 6 minutes right off the gate with no one from the actual Wu family, and then here’s the first disc grinding to a halt thanks to Cappadonna’s sex verse on “Maria” (one of the most abysmal verses I can think of), and then here’s the second disc shoving a bunch of chaff at the end.

I will say Deck is on point throughout, and his verses on “Hellz Wind Staff” (with its sleighbell shimmer), and “Triumph” especially, are not just the best on those songs, but the best on the album. RZA believes that Ghost’s verse on “Impossible” is among the best ever, and it simply can’t be, not with Deck going “I bomb atomically, Socrates’ philosophies and hypotheses / Can't define how I be dropping these mockeries / Lyrically perform armed robbery / Flee with the lottery, possibly they spotted me.”

GZA mocks Wu-Tang’s enemies on “As High As Wu-Tang Gets” and I can’t think of better advise for this album as a whole: “Yo, too many songs, weak rhymes that's mad long / Make it brief, son, half short and twice strong.”

2000’s The W has aged well. Except the bright pop cut “Gravel Pit,” the beats are off-kilter, dark, and minimal in a way that makes me think Kanye West was trying to absorb this for Pusha T’s My Name is My Name. Likewise, I think Kendrick Lamar based his vocal outpouring on “u” based on Ghostface Killah’s touching vocals on “I Can’t Go To Sleep” and “Jah World,” rare cases of any of these rappers trying to use their voice as a voice. Some of the hooks (“Careful” with its gunshots, and ODB on “Conditioner,” a song that’s far too long and an uninteresting beat switch) leave a little to be desired, ditto guest verses from Nas’ (a line about throatpies, pissing and causing anal stitching all in one breath! Nice!) and Busta Rhymes (“You ain't knowing my name tattoo-ed on your bitch arm,” really sick burn, bro! You cucked me!), but this album has atmosphere that Wu-Tang Forever didn’t.

Unfortunately, Ghostface Killah’s first verse on “Rules” has negatively colored my impression of Iron Flag in its entirety, whereupon he ‘responds’ to 9/11 by asking the hard questions (“Who the fuck knocked our buildings down?”, did you read the news today, oh boy?) and ends by telling George Bush that he will somehow manage the war. (It was Gary Suarez who once pointed out the great irony in GFK threatening to blow up the terrorists should they ever come around his hood.) It’s big, dumb ‘Freedom Fries’ energy. But even ignoring that, I don’t think this is a good album. The RZA productions feel like pale imitations of others: “Chrome Wheels” is a poor attempt at a DJ Quik beat (wherein Prodigal Sunn rhymes sound with sound, “Pedia Brown, media surround my sound / When you see me in the hood of ya town, respect my sound”); “Soul Power” is a Eric B beat. Meanwhile, “Uzi” has a really happy horn loop which doesn’t gel with these rappers while “Radioactive” has a looped squeal every other beat that gets tired quick. Someone named Madame D shows up on two songs, continuing RZA’s fascination with an American Idol’s idea of soul following Blue Raspberry’s appearance on Raekwon’s solo album. Cappadonna is no longer here besides the hidden track (uncredited), and he is even airbrushed out of the cover. Sometimes I think he deserved better but then I remember his verse on “Maria.”

If you get past the corn factor on 2007’s 8 Diagrams, then you would have a solid album. But the corny tracks are the album’s longest songs, and so there’s really no way around it: “The Heart Gently Weeps” runs 5 minutes, “Stick Me for the Riches” gets 6 minutes, and “Life Changes” is 7 minutes. A lot of people consider the lattermost to be a highlight, the group all coming out to tribute the departed Ol’ Dirty Bastard who passed away in 2004 from a drug overdose, but the verses are short and after each member is the chorus: this isn’t like previous posse cuts where there was no time for bullshit. Instead, the whole thing plays like a parade of filler and the emotions feel nonexistent or forced. “I became weak when I heard that his body expired / It was hard for me to believe my brother retired” is pathetic, and if someone said that at my funeral, I’d wake up to smack them, and that came from blood family! “The Heart Gently Weeps” doesn’t invite replays, lovely as Erykah Badu always is, and the words “feat. Dhani Harrison & John Frusciante” make my stomach queasy. Meanwhile, Gerald Alston, whoever he is, I don’t care, goes on for far too long on “Stick Me For the Riches.”

All that being said, “Campfire,” “Get Them Out the Way Pa” and “Wolves” are all good songs for their samples, verses and features (George Clinton), respectively; Method Man is curiously strong on this album. Best of all is “Unpredictable,” whose beat actually does feel that way, all industrial squeals and screams, and even an electric guitar that blends into the metal. Not a good album, but it deserves more praise as the Wu-Tang Clan album with the last great RZA beat.

The next two albums dropped the ‘Clan’ from the billing, as if to separate these albums from the canon with good reason: they both suck. RZA doesn’t produce a single beat for either. Only 8 out of 2009’s Chamber Music 17 tracks contain any rapping at all, which is less than half, so the album feels filler-loaded but frankly the songs with rapping aren’t exactly good to begin with. The beats themselves are courtesy of ‘The Revelations’ and live bands that are bullied into sounding like looped samples just aren’t as interesting to me as either live bands pretending to be human fucking beings, or looped samples. It’s the least-memorable Wu-Tang (Clan) album, and the worst because of it.

2011’s Legendary Weapons is more cohesive without every other track being an instrumental but producers Noah Rubin, Lil' Fame & Andrew Kelley rely so heavily on dusty drums and keyboards/organs such that every song sounds the same. Not helping is that almost every song here deploys a sample as a hook. GZA and Masta Killa are absent, and so there’s a lot of verses from Ghostface Killah to pick up the slack, which would be a positive except none of them are good (“I don't touch that swine, I want that unnecessary beef / You smoke garbage buds, we smoke tons of keef / Fishing, looking for that big-mouth bass” is indicative: it doesn’t follow any sort of narrative logic). He gets outclassed by relative newcomer Action Bronson whose voice made people compare them a lot, and who also got hyper-specific about food (“Poppy bagels getting flavored out in Syria”) in a way that reminds of me of the old Ghostface Killah. Some of the vocals seem oddly mixed; Method Man seems muted on “Diesel Fluid.”

Wu-Tang Clan are a case study of rappers who don’t want to grow up, don’t even want to pretend to grow up, continually content to churn out worse and worse songs so long as they sound like their earlier songs. Hence the nostalgia dump that is 2014’s A Better Tomorrow, whose title recalls Wu-Tang Forever and whose first song is titled “Ruckus in B Minor.” Any album where RZA makes a brag about being at Coachella just makes my brain wither (“Holla at the moon, my goons at Coachella”) but the first two songs aren’t bad, with “Ruckus” produced by Adrian Younge (who single-handedly saved Ghostface Killah’s late period, although I find his touch to be so limited and boring now) and “Felt” seeing RZA testing out drum and bass (too thin!). “Miracle” and “Preacher’s Daughter” are awful songs.

The acronym “Cash Rules Everything Around Me” turned out to be more prophetic than anyone would’ve liked, so there was the sole pressing of Once Upon a Time in Shaolin that pharma-man (pharman?) Martin Shkreli purchased for $2 million at an auction, a laughable amount of money considering what the group had become. (I haven’t heard it - I don’t even want to hear it. Fuck bullshit like this.)

2017’s The Saga Continues is similarly billed under ‘Wu-Tang’ as those 2009-2011 albums. Sean Price makes a comment about drag being weird in a verse that sucks besides that. RZA makes a queerphobic line too (“Bobby Dig convert Lady Gaga back to heterosexual”). R-Mean considers this repetition of rookie and veteran to be wordplay, “The type of rookie that's respected by the veterans / 'Cause dog I ain't a rookie, I'm a motherfucking veteran.” That’s all I remembered about this album after just playing it.

Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) - A+ Wu-Tang Forever - B The W - B Iron Flag - B- 8 Diagrams - B Chamber Music - D Legendary Weapons - D A Better Tomorrow - D Once Upon a Time in Shaolin - N/A The Saga Continues - D

Mostly mediocre if not outright bad albums or not, listening to nine albums is easy-peasy! You can crush that out in one day. What’s harder is listening to their solo albums, which only an insane person could do.

Ghostface Killah

The beating heart of the group since he’s the only one that still put in effort for many years there. He’s also the group’s best talent. His storytelling prowess is second to none, laced with strange, absurd, and even psychedelic details that prove how much he loves, not just rhyming and ladies, but food and smells and senses too. (The Raymond Chandler of rap.) Case-in-point is on “Shakey Dog,” where the robbery narrative suddenly takes a detour to mention the food being cooked, “Passing they rum, fried plantains and rice, big round onions on a T-bone steak / Yo, I want some” in a way that elicits a, “yeah, I want some too!” Notice the slightly lower register when he says, “Yo, I want some”: he’s hungry, yes, but he’s too smart to waste any time taking a bite.

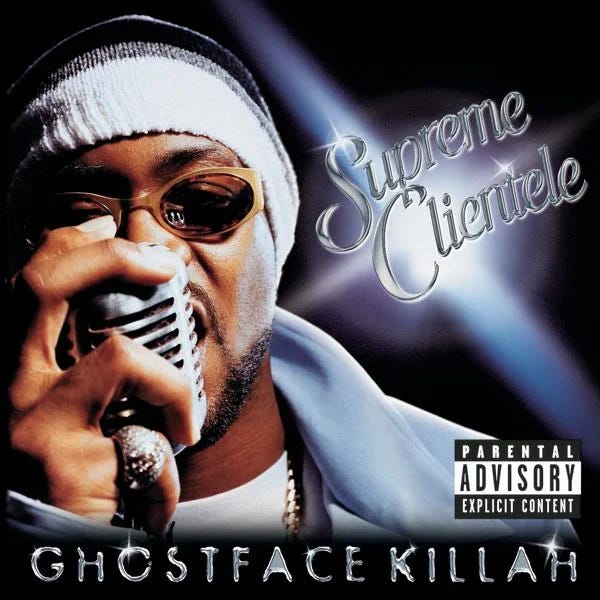

But from a sheer quantitative POV, I count three classics to his name whereas other Wu solo members are lucky to have one—Ironman, Supreme Clientele, and Fishscale—and he kept his head above water until (take your pick) 2006, 2009, or 2013 while his friends dropped off hard well before that (usually 1999).

Ironman slams so hard all the way through “Daytona 500” (which rides the same sample as EPMD’s “Brother not a Jock,” but louder; it’s a bonafide rock song) but then grinds to a severe halt as they shove all the slow ballads at the end. (Not helping is that all the songs in the final stretch are the album’s longest. In fact, that so many of the songs are so short in the first half makes it feel like a MF DOOM album.) And the verses are so dense with detail, that it’s the biggest grower in his discography, scratch that, in all of the albums that are covered on this page, and as he doesn’t bother with the occasional pop/R&B cut that’ll pepper his albums going forward, it’s up to RZA to supply beats as hooks: the icy keyboard of “Wildflower” or the ambiguous squeal of “Assassination Day” or the Al Green sample on “260.” Strangely, Ghostface Killah gets outrapped on his own album on two occasions, both from Raekwon (“The Faster Blade” and “Daytona 500”). On the other hand, Cappadonna mostly sucks next to these two Gods; his verse on “Daytona 500” tries so hard, it’s kind of cute, while his flow on “Camay”—the romantic cut to off-set the misogyny of “Wildflower”—is basic where it sounds like he’s trying to land the next rhyme (“Halle Berry rhymes with…ferry!” you can practically see in a thought bubble behind him) to the point that I don’t believe for a second that his verse on “Winter Warz” was a freestyle. As for the last stretch, “All That I Got Is You” is too much honey and feels tonally out of place with an album that features as disgusting and vile (and incredible) a song as “Wildflower”; “The Soul Controller” gets ambitious by reimagining Sam Cooke’s immortal song inside a haunting house, although I’m not convinced RZA pulls it off.

Supreme Clientele sags in the middle (Six July’s string line on “We Made It” is a little too major chord for Wu rappers; I’m not sure what RZA was going for on “Stroke of Death”), but it starts unbelievably strong and sticks the landing in its ending stretch from “Malcolm”-onwards. The beats are more pop-colorful than that of Ironman without going full-pop, while Ghostface Killah’s prose is psychedelic (Pitchfork’s Jeff Weiss: “To understand Supreme Clientele is to be humbled by epistemological limitations. You can see, feel, and taste it, but it can only be decrypted to a point. It’s a psychedelic record moored in reality”). It’s desert island music because it’s desert island poetry: “Sunsplash, autograph blessing with your name slashed / Backdraft, four-pounders screaming with the pearly ash / Children fix the contrast as the sound clashes”; “Those were the days, made faces in school plays / Paper trays, city wide test, made half a days.” These are words that live rent-free in my head.

Fishscale is more colorful than that, made possible by a rotating door of producers, including MF DOOM (who is responsible for the most beats here at four songs), J Dilla, Pete Rock, and Just Blaze, among others. Children’s choir-chant a la Kanye West’s “We Don’t Care” on “Kilo”; crossover hit placed wisely in the middle of the record on “Back Like That”; the most inventive “Family Affair” sample ever(?) on “Dogs of War” but cutting off the word ‘affair’ so it just loops “It’s a family” as Ghost brings his son on board; “Jellyfish” (“She must be a special lay-dy… / And a very exciting girl”) and “Underwater” are more overtly psychedelic than almost everything on Supreme Clientele. (The Alchemist pulled liberally from the lat ter on “Blackest in the Room” for Freddie Gibbs.)

But Ghostface’s rapping doesn’t have the same fire as the previous two records, “Shakey Dog” being the big exception which is one of his best performances. Put it this way: the two Dilla beats from Donuts (“Hi.” —> “Beauty Jackson” and “One for Ghost” —> “Whip You With a Strap”) aren’t improved on with a God MC gracing them, which physically hurts me to type, but you know it’s true. Raekwon’s “verse” on “Kilo” makes me wish he actually wrote something down instead of listing out different-coloured tops even I dig it. And of course, Ghostface Killah might have the best music to worst skit ratio in all of hip-hop. Regardless, no one else from the Wu family was operating on this level in 2006. And to prove it, Ghost released a collection of b-sides that same year on the aptly-titled More Fish.

The tagline that followed Ghostface Killah for years was that he’s ‘consistent.’ Compared to ODB or Raekwon or GZA, sure. That’s not saying much. But there’s a huge discrepancy between these three albums and Bulletproof Wallets, The Pretty Toney Album, and The Big Doe Rehab, albums that feel like leftovers, placeholders or victory laps, respectively, and don’t have distinct vibes to them. Ghostface Killah blames some of the failures of Bulletproof Wallets on sample clearance issues (“‘The Sun’ or ‘The Watch’ were my favorites on Bulletproof, but they didn’t make the album”; “With ‘The Watch,’ Barry White didn’t want to clear the sample. He didn’t want me to use it. […] And RZA, he couldn’t find the fuckin’ sample for ‘The Sun.’ Motherfuckers get high, and he didn’t know where he put it at”), but I can’t see a few songs improving the album that much. The Pretty Toney Album is supposedly his pop album, but the songs don't actually invest themselves in pop music, especially compared to what Kanye West and Jay-Z were doing around this time, so what results is a compromise: beats that simply don't engage, which also means that I'm less invested in the actual rapping. “Shakey Dog Starring Lolita” is emblematic of The Big Doe Rehab as a whole: there’s less energy, and Sean C & LV, who handle most of the album’s production, aren’t as good as a revolving door of MF DOOM, J Dilla, and Pete Rock.

I glossed over the Trife da God collaboration, Put It on the Line, because the album plays like a Trife da God solo record with a few Ghostface Killah solo tracks to make it more enticing. Title track aside, the best songs are all Ghostface’s, and while Trife da God holds the line, he does get embarrassingly corny from time to time (“I'm the definition when you mix heat with friction” —> friction creates heat, dude).

Personally, I draw the line in the sand in 2009. Ghostdini: Wizard of Poetry in Emerald City got a lot of derision, some of it not completely unfounded because of the not-surprising rampant misogyny and unfortunate lyrics about sex (“Before I bust babe, I think I’ll cum in your butt”), but I still think it’s braver than the records that he released afterwards, which all read like corporate apologies for trying something different. (Had Ghostdini been released in 2012 where it became hip to like R&B, and featured the Weeknd, Frank Ocean and/or Drake instead of Raheem Devaughn and John Legend, it would’ve been better received.)

In 2010, Ghostface, Method Man and Raekwon released Wu-Massacre on Def Jam. Raekwon described the making of the album, “A lot of the production was dealt with through us playing phone tag,” which explains why only 25% of the songs here contains input from all three rappers. The first three songs are all nostalgic cash-ins, and also the best songs on the album; RZA’s beat for “Our Dreams” is awkward and clanging outside of the Michael Jackson sample. No thought went into this album from anyone involved except whoever they tapped for the cover.

In 2012, Ghostface Killah teamed up with Sheek Louch of the Lox for Wu-Block, an album that sounds very much akin to his previous solo album, Apollo Kids, by which I mean an album you play once, nod along to the beats, and then never even think about ever again. There’s a decent soul sample on “Crack Spot Stories,” which Frank Dukes’ “Different Time Zones” later on sounds suspiciously similar to. Ghost is absolutely incoherent on “Pour Tha Martini” (“Feeling like Bruce Wayne, making up for never making the prom / Ma, you chilling, the belt glow in the dark”) while Erick Sermon turns in a kindergarten keyboard line on “Do It Like Us.” The best song is “Drivin Round” thanks to the jazz fusion keyboards and the rare Erykah Badu feature (albeit underutilized).

Adrian Younge’s production for Twelve Reasons to Die and its sequel have aged fine in the sense that dusty drums and 60s’ organs will always sound good, but there’s an emptiness in Younge’s soul (hence why Younge’s album for Bilal, In Another Life—right after Bilal went glitchy to surreal effect—around this time was a total flop), not helped by Ghostface Killah who feels the need to continue storytelling even though he had run out of any stories to tell. The concept of Twelve Reasons to Die is a mix of mafioso rap cliché and comic book camp that reads like a bad fanfic: Ghost gets murdered by his employees and baked into 12 vinyl albums and comes back for revenge, but he doesn’t sustain interest by providing any actual details that the Ghostface Killah of ‘96 would have.

But Twelve Reasons to Die gave Ghostface a new (old) sound to plunder, which is what he did by linking up with the Revelations (from Wu-Tang’s Chamber Music, you remember) for 36 Seasons, and then BBNG for Sour Soul, and then Twelve Reasons to Die II, and with each passing album, he leaned more and more into that nostalgic sound as a crutch. 36 Seasons is yet another concept about how Ghost was in jail for and now out for revenge. There was a certain mystique to the name Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), and I never needed to know what it referred to, so to hear RZA’s explanation years later that it referred to the chambers of their hearts (9 people * 4 chambers per heart = 36 chambers) made me groan, as does Ghost going “nine years, that’s 36 seasons.” The Toronto cross-over jazz outlet BBNG aren’t really allowed to display their technical chops even with a few instrumental tracks. And on the sequel to Twelve Reasons to Die, Ghostface gets showed up by the features, including old pal Raekwon and Vince Staples.

For all their flaws, at least these albums have been blissfully short, and they play like masterpieces compared to The Lost Tapes and Ghostface Killahs which came after and when any consistency truly went out the window. The Lost Tapes is a collection of leftover verses from Ghostface over new beats from Big Ghost, and is not like the Nas album of the same name which held some career highs. The rapping gets embarrassingly abysmal in points: Ghostface goes “But you the most beautiful-est thing I seen all week / And I don’t even know your name or how you speak” and “Come on now, we can spend Arabian Nights / I could take you to my mosque and we can pray all night” while KXNG Crooked drops this blunder, “I giver her the hammer, I call it a blammer, that’s onomatopoeia / Go look it up, you don’t read books enough” (dude, everyone knows what an onomatapoeia is). The posse cut remix featuring Snoop Dogg, E-40, and Tricky is two decades too late. Ghostface Killah sounds more awake than he has in years on “Me, Denny & Darryl,” the opening song on Ghostface Killahs, and then the rest of the album just happens: it’s his worst album by a fair margin, and the cover makes me think he took those Purge movies far too seriously.

All that said, with the exceptions of GZA/Genius (for one album) and arguably early RZA, Ghostface Killah was the only rapper in the Wu family who cared about ‘artistry’ and not merely beats and bars.

Ironman - A Supreme Clientele - A+ Bulletproof Wallets - B The Pretty Toney Album - B Put It on the Line (with Trife da God) - B Fishscale - A More Fish - B The Big Doe Rehab - B Ghostdini: Wizard of Poetry in Emerald City - B- Wu-Massacre (with Method Man & Raekwon) - D Apollo Kids - B- Wu-Block - Wu-Block - B- Twelve Reasons to Die - B 36 Seasons - B- Sour Soul - B- Twelve Reasons to Die II - B- The Lost Tapes - B- Ghostface Killahs - C

GZA/Genius

Hyper-intellectual wordplay earns his original moniker , The Genius, under which he released one album before Wu-Tang Clan, Words From the Genius. Any interest I might have had backtracking there is completely nullified by one of the vilest songs in hip-hop history, “Stay Out of Bars,” whereupon GZA encounters a transgender person and proceeds to ‘massacre’ everyone at the club because she said hi to him in a deep voice. I guess ‘Genius’ doesn’t include emotional intelligence?

Hard to say what ‘Genius’ does entail. There are songs in his discography after he became GZA that incorporate record label names (“Labels”), rap magazines (“Publicity”), celebrity names (“Fame”), and NFL teams (“Queen’s Gambit”) in flashy ways, but it’s also set to a deadpan voice that makes it hard to care about what he’s saying, and a flow that got more and more fatigued as he got older. And honestly, those songs became gimmicky over the course of his discography as he felt the need to deploy one on each new album, nudging and winking at you to agreeing with how clever the Genius supposedly is.

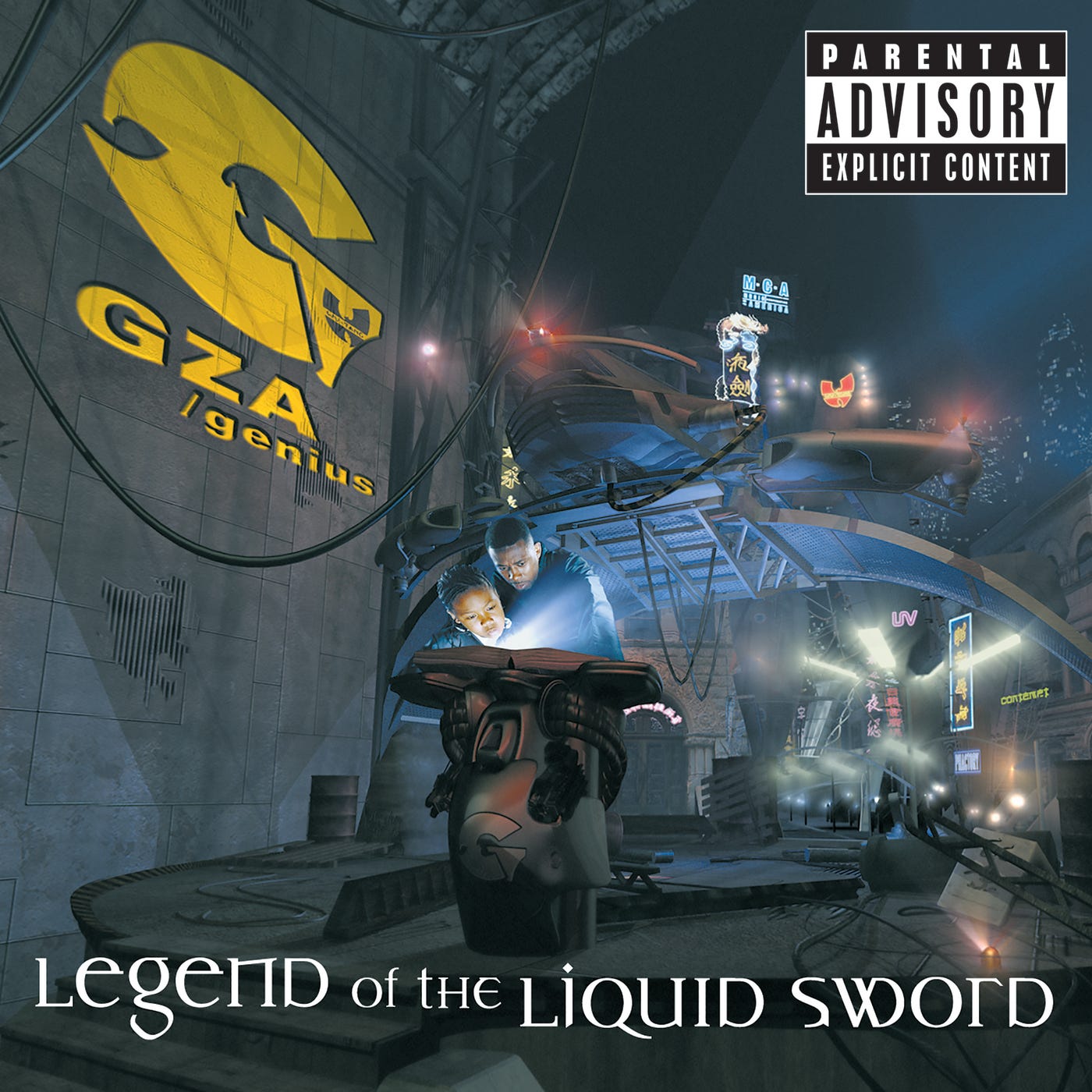

So I’ve never bought into the cult of Liquid Swords, an album that’s far more insular than other Wu albums because GZA has no interest in the world outside of RZA’s basement, evidenced by the fact that the title track and opener has such a bounce to it but doesn’t groove at all (I love those drugged out backing vocals on the hook). (Ian Cohen’s Pitchfork review notes that “The album’s lack of commercial ambition is also reflected in its status as one of the least sexual hip-hop records ever made. Off the top of my head, there are probably two total lines which acknowledge women as physical beings,” but I don’t take that to be a positive: I want my albums to acknowledge the physical world I live in). RZA is the true star here, whose beats sound like a dark sci-fi fantasy in their dying star groans of keyboard and guitar.

Beneath the Surface is perhaps the worst-sequenced hip hop album I can think of. You get the obligatory hip-hop intro that ends with a drum loop that doesn’t even bother segueing into the next song which starts with a completely unrelated drum loop. Then soon, there are two skits (only Kanye West got away with this move on The College Dropout), the latter of which talks about increased police brutality against minority communities which leads into ODB yelling “I'm gonna crash your crew!” when “Victim” was right there. (Not saying that “Victim” is the better song or anything, just that it would’ve made sense there. In fact, “Crash Your Crew” is the best song here.)

The chief issue with Beneath the Surface which applies to the rest of GZA’s albums moving forward is that someone nicknamed ‘Genius’ would stoop to beats as simplistic as these. Not bad, just simplistic. On Beneath the Surface, the beats by Mathematics and Arabian Knights are usually whistle-clean with lots of strings to give them a cinematic sweep that just isn’t earned, and the lone RZA contributions on both Beneath the Surface and Legend of the Liquid Sword tend to be the most egregious examples. It isn’t just the skits that stretch out the track-list on Beneath the Surface: “Hip Hop Fury” and “1112” are posse cuts with loops that just aren’t good enough to juggle this many rappers, especially when they go on and on so we can hear from *checks track-list* ‘Timbo King,’ ‘Dreddy Kruger,’ and ‘Njeri Earth.’ Legend of the Liquid Sword has the same issue: I don’t care who ‘12 O’Clock’ and ‘Armel’ are. There’s another posse cut on the album titled “Fam (Members Only),” which only features Wu members, and that’s how they—all of them—should have kept it.

Arabian Knights once again handles a large handful of Legend of the Liquid Sword, but I find the beats from the others far more attractive, particularly the funky cuts by Jay Garfield (“Knock, Knock”) and DJ Muggs (“Liminal”); shouldn’t Arabian Knights’ “Sparring Minds” have been 4 bpm faster? Anthony Allen, who can’t sing a single note, singlehandedly ruins what would have been a formidable run from “Knock, Knock” through “FAM (Members Only),” not that the beat of the title track is any good, trying hard to recreate RZA’s gritty bounce on “Liquid Swords.” The cover, replete with the disproportionately photoshopped kid’s face, is the most memorable part of this album, so that’s the one I’ve decided to use for GZA. Oh, and “Witty Unpredictable Talent or Natural Game” from “Auto Bio” doesn’t spell ‘Wu-Tang,’ Gary, it spells ‘Wu-Tong.’ So much for Genius!

DJ Muggs had the best beat on Legend of the Liquid Sword so he produces the entirety of 2005’s Grandmasters, an album that would’ve ranked as GZA’s second-best album if he didn’t sound tired throughout. I guess it still does by virtue of there being nothing else, actually. “Queen’s Gambit” is a snooze-fest about a time GZA make a girl squirt (“I had all three in a huddle / Bucking like a colt, before I released them puddles”), and I just can’t bring myself to care about the narrative or the use of NFL teams without reading a lyric sheet. That said, “Exploitation of Mistakes” deploys an interesting news reporter flow. DJ Muggs’ beats have a little more darkness to them, a little more life, than what Arabian Knights was cooking up last album, and ODB tribute “All In Together Now” (with an impressive rhyme sequence from GZA in the second verse) is closer to the classic Wu sound than anything from the previous two albums, although “Destruction of a Guard” deploys an annoying vocal sample every measure.

Pro Tools doesn’t even invite you to listen to it with its title (“The people at [label] Babygrande were asking for a name. I was looking around the house, or the studio, and trying to come up with something, and I may have even been reading the actual Pro Tools manual and just went with that”) and cover, but GZA is doing his best throughout: for example, you can’t imagine any of the other Wu members attempting to leverage the alphabet on “Alphabets,” even if it’s (disappointingly) just for the chorus. RZA’s beat, “Life is a Movie” is one of the laziest sample deployments ever (using Gary Numan’s “Films”) and points to RZA’s failure after getting money: his basement stuff sounded more sci-fi than his try-hard Hollywood beats. Black Milk doesn’t hand in his best either, but given that he fully produced Tronic and mostly handled Elzhi’s The Preface that year, I forgive him (not helping is that GZA drops this blunder as the second-line, “MC’s are like sperm cells, a gang of us”). Famously, there’s a 50 Cent diss track here titled “Paper Plate” (with an unfortunate garbage drumbeat), and I don’t know why GZA thought it was worth responding to Fiddy ten years after 50 Cent’s single, but here we are. GZA further contextualized the song on MTV, saying “there is so many things to be inspired by, so I don’t understand why people are still rhyming about the same thing,” and dude, you don’t need to call out your pals Raekwon and Meth like that!

Liquid Swords - B+ Beneath the Surface - C+ Legend of the Liquid Sword - C+ Grandmasters - B Pro Tools - D

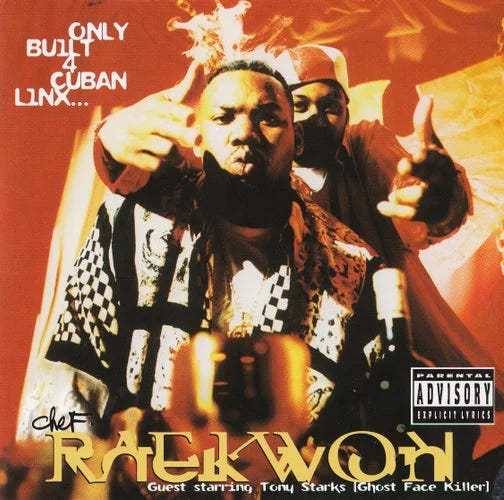

Raekwon

Tremendous rapper but terrible artist. The feeling I get from Raekwon is that he doesn’t care about anything other than bars. Key to that assertion is that his discography sucks: blink Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… out of existence, and Raekwon would have the worst discography of any major, critically-acclaimed rapper in existence; Nas’ current late-game resurgence since hooking up with Hit-Boy—two trilogies that are not as good as reported but also way better than the chaff he used to make—is beyond Raekwon’s reach. After no longer working regularly with RZA (“RZA had a vision, instead of cooking coke in the kitchen,” he explains on “All Over Again”), Raekwon linked up with mostly nobodies or, at best, Wu affiliates that weren’t making their best work anyway. Put another way, GZA picked better beats, a damning statement.

Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… might have been the best Wu-related album ever if Raekwon kept it to 13 songs like Tidal and Liquid Swords—even though there’s not that much filler—I wish Raekwon didn’t bully RZA to making 70 minutes’ worth. Personally, I’d cut the skits, the Blue Raspberry song (comedy gold though: Blue Raspberry vomits out some words and then a sample goes “You sang beautifully just now”), the remix of what I suspect was the weakest song on the original album, and “Ice Water” because the sample is annoying.

With the exception of Ol’ Dirty Bastard (who only shows up on the uncredited song, alas), this is the Golden Mean of the first wave of solo Wu: cold basements and dark alleyways, set to a rich cinematic sweep. “Knuckleheadz” sports two incredible verses from both Rae and Ghost—poor U-God, set up for failure like that—with the former rhyming “Amarettos and chewables” with “Smacking pharmaceutical” and Ghost going “Run up in his lab, take off the mask Chas, and think fast / Don’t laugh, grab the hash, don’t forget the stash / Grab the tear gas and place it in his face fast / At full blast.” “Criminology” might be the best banger in boom bap history, just an incredible flip from RZA who bakes the funk-on-its-way-to-disco “I Keep Asking You Questions” by Black Ivory and pitch-shifting it from groove to banger (“RZA bake the track and it's militant”). “Ice Cream” is the most twisted ‘for the ladies’ track there ever was, thanks to a female vocal sample that’s less a moan and more a cry for help, undercut by the rappers over top. Nas’ verse on “Verbal Intercourse” outdoes anything he did on Illmatic. “Through the lights, cameras, and action, glamor, glitters and gold” is how he starts, like the start of a great soliloquy, and then he goes on to rhyme “gold” with “I unfold the scroll,” and it truly feels like he’s doing just that: unfolding the scroll and imparting all this language knowledge to us heathens. And then the rhymes start coming, first the ‘ee/ea’ sound: deceased-beast-yeast-peace-streets. Then, the ‘o’ sound: wisdom-imprisoned-son-smoke-gold-hold-non. Then, the ‘au’ sound: nonchalantly-raunchy-haunts. And then we get the ‘i’’s (Rikers Isle-minds-life-wife) and ‘u’’s (womb-tomb-presume-salute-ritual). Nas somehow uses up so many different vowel sounds delivered in a web of internal rhymes, and moves through them with such finesse, and I rank it higher than almost every verse on Illmatic.

Immobilarity and The Lex Diamond Story—the albums released between the only two Rae solo albums anyone cares about—are both pitiful offerings, with beats provided by The Infinite Arkatechz, Triflyn, DJ Devastator, Mizza and someone named Crummie Beats that turned out to be far more of a self-fulfilling prophecy than I bet they would have preferred. You excited? No, you don’t know who these people are? Me neither! And after listening to these albums, I don’t want to know. Not helping is the knotty, gritty Raekwon that we know and love isn’t on those albums: the rhyme scheme and flow on “All Over Again,” notable for being a Kanye rip, are heartbreaking. Mizza’s Dells sample on “Pit Bull Fights” would be put to better use when Exile used it on Blu’s “The World Is…” while Emile’s beat on “Robbery” sounds like hackwork, and “Ice Cream 2” is cheesy R&B in a way that makes me wonder if Raekwon understood what made the original so good. (A pull-quote, straight out of Wiki: “Raekwon has stated that the title [of Immobilarity] is an acronym for ‘I Move More Officially by Implementing Loyalty and Respect in the Youth.’” Stop trying to make Immobilarity happen.)

I know some people go nuts for the sequel to Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… but it’s one of those many cases in hip-hop where a sequel has nothing to do with the original (see also: Jay-Z’s two trilogies, Curren$y’s Pilot Talk III, Young Thug’s Slime Season) and here’s how I know: RZA is barely here. Instead, the album is produced by a revolving door of departed’s (J Dilla), not-yet-great’s (The Alchemists), has-been’s (Erick Sermon, Dr. Dre) and was-never’s (BT). And whereas Ghostface Killah was on practically every song on the first album, he’s just a glorified feature here. Case in point is the song by forgotten horny man Necro, “Gihad,” where Raekwon lays down a bog-standard verse about the ‘streetz’ and then Ghost follows up with a completely different verse about getting a blowjob from a woman who turns out to be pregnant and who turns out to be someone else’s woman and who turns out to be a whore who got fisted one time. He nuts on “the side of her mouth.” Not in her mouth, or on her lips, but the side of her mouth. The cheek, I guess? It’s fitting for a Necro beat, but it’s not fitting for the song, and doesn’t inspire replay regardless. What I’m saying is, treat this less like a sequel and more like another Raekwon solo album - just a better one than the others.

“Catalina” and “About Me” are the Dr. Dre beats, flanking a song that interpolates Queen’s “We Will Rock You” as “We Will Rob You” (it’s as endearing and cheesy as it reads). Neither Dre productions are good, with the former having a cheap exotica to it that is reminiscent of too-many early-2000s hip-hop beats that sounded like they were made to be played on a yacht and nowhere else, and the latter sounds like a second-drawer beat from The Eminem Show. Better are the two RZA beats, “Black Mozart” and “New Wu,” which is what you wish RZA was making more of instead of the fodder he was churning out at this point for the group at large. And better yet are the beats from Marley Marl (“Pyrex Vision” might be the best hip-hop song clocking under a minute, pure winter steel) and MoSS (“Have Mercy” has a drum clack that’s enticing, and Beanie Sigel runs away with one of the most quotable lines on the album, “But it's hard to raise my boy from this visiting room”), while “House of Flying Daggers” bangs harder than most Dilla beats, including the other two that make their way here. It’s a B+ album that so desperately wants you to believe it’s worth more; gorgeous cover though. In terms of 2009 and veterans playing around with shorter song lengths, I’d rank it below Mos Def’s The Ecstatic but ahead of MF DOOM’s Born Like This.

Scotch “Chop Chop Ninja,” “Rock ‘N’ Roll,” and the dying elephant horn beat of “Molasses”—uncoincidentally, the three longest songs on the album—and 2011’s Shaolin vs. Wu-Tang could have been successfully billed as ‘Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… Pt III’: not only do a handful of names from last time show up here again (The Alchemist, Mathematics, and Erick Sermon), but Raekwon’s rhymes are still engaging (“They pushed his face in, fell out his Saucony's, snatched his homeys / Took his Glock, you gon' be my tenderoni?”). It’s his third-best album, easy, with many of the songs short and to the point (the average song length is under 3 minutes), which means that though the string arrangements can be simplistic (the title track; “Rich and Black”), it’s never bothersome. “Masters of Our Fate” would’ve been the best song if he didn’t bother with those sampled choruses which eat up so much time, and kept it 2 minutes like the rest of these songs - it still has the album’s best verse, courtesy of Black Thought.

Raekwon’s last two albums are better than Immobilarity and The Lex Diamond Story, but they’re also worse in their own way. Fly International Luxurious Art elicits an eye-roll from the title alone (stop trying to make F.I.L.A. happen), and Raekwon linking up with A$AP Rocky, French Montana, and 2 Chainz has a stinky miasma of desperation to it (it’s not 2013 anymore, dude). Raekwon might be rapping with a little more fire under his ass, but with beats this bright, it’s hard to notice or care. “Soundboy Kill It”—originally released in 2013 where the Assassin feature-as-climax made sense—is emblematic: the beat is 99% its monolithic drum pummel, and then it grinds to a halt for the pop choruses spliced in from a completely different song.

The first third of The Wild makes you anticipate a 90s’ throwback album that never comes, and it loses the plot around when Lil Wayne shows up because it’s set to a strangely glitzy EDM beat. I’m not sold on that opening salvo anyway, not when the first real song liberally recycles the sample from the Roots’ “Don’t Feel Right” (Ohio Players' “Ecstasy”) and then the supposed album highlight “Marvin” brings in Mr. “People who have really been raped REMEMBER”—can’t believe this man is still getting work or has his songs going viral on Tik Tok—for a chorus that sounds nothing like the singer he’s supposedly tributing. (That said, “Nothing” glimpses the old Raekwon, the one that loved rhyming and words.) There is a G-Eazy feature for some reason (“Forever may not exist but who else is as hot as this?”).

Only Built 4 Cuban Linx... - A Immobilarity - D The Lex Diamond Story - D Only Built 4 Cuban Linx... Pt II - B+ Shaolin vs. Wu-Tang - B Fly International Luxurious Art - C The Wild - C

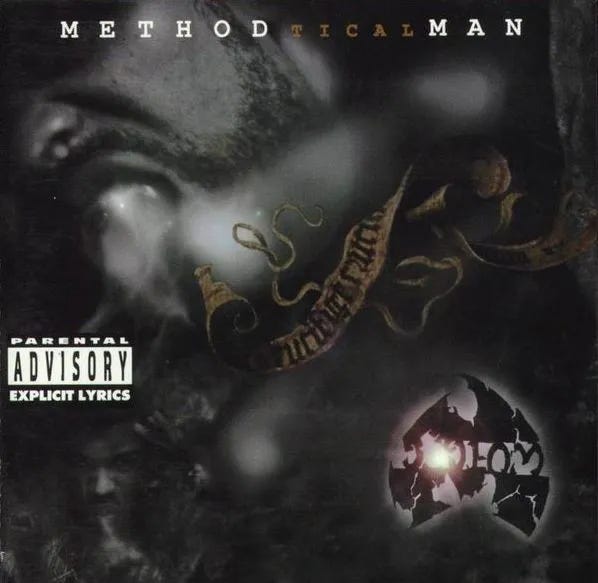

Method Man

Based only on performances in 1993, I would easily nominate Method Man as the group’s best rapper, but that might be unfair since he was the only one that was granted a solo spot. Method Man’s debut album, Tical, was the first to arrive the following year, and he doesn’t move the needle. It’s a good album, but it’s quickly overshadowed by the solo albums by Raekwon, GZA, and then Ghostface Killah where each one moves Meth lower and lower on the list. Method Man is fun to listen to; his voice feels like you’re with a friend who you know is about to get wild, like a more cohesive Ol’ Dirty Bastard, but he’s nowhere near the inventive wordsmith as his peers, and that he goes most of the album completely solo highlights that fact, even if he beats Raekwon on the battle rap. RZA’s beats are getting less eclectic just one year after his grand debut as what could’ve been the east coast’s next-best eclectic after Prince Paul—is that another Wendy Rene sample from the same song that he mined for “Tearz” on “Simulation?”—the alleyways are darker this time, and thus less jazzy and more interchangeable as a result, but I love the Boards of Canada-like intro for the title track and the Jerry Butler sample on “Bring the Pain” while Meth goes “In your Cross Colour clothes, you’re crossed over / Then got totally Krossed Out and Kris Krossed / Who the boss? N****s get tossed to the side.” Some songs like “All I Need” and “Sub Crazy” feel like NYC versions of the trip-hop sound happening in Bristol.

If you consider Tical to be a lesser version of Enter the Wu-Tang, then you can consider his follow-up Tical 2000: Judgement Day to be a lesser version of Wu-Tang Forever where everything seems bigger but not necessarily better. 73 minutes this time, with a skit after every song—including one of Donald Trump asking Meth where the album is—and often for slim rewards. “Sweet Love” is a very slow moving song so that Method Man can go “My finger's on the clit splashing / Your pussy lips got you spazzing / Love juices, marinating in your satins” and “Whattup, went to beat it up, I'm not the one to eat it up / But the type to hit it raw dawg and seed it up,” lines so bad they made me think I was still listening to Cappadonna (“Sex was on my mind like cum was in my pants”). Meth tries to re-capture the magic of crossover hit “I'll Be There for You / You're All I Need to Get By” on “Break Ups 2 Make Ups,” which would be a total dud if not for the fact that D’Angelo always sounds good over natural instrumentation as Meth’s lyrics are generic women-hating bullshit.

Tical 2000 had a loose concept about the end of the world occurring in the year 2000, so Method Man got in another one just before the apocalypse, teaming up with Redman for Blackout!, an album that seems better and better in hindsight with every new Meth album released afterwards, of which there have been too many. Released in the year of hip-hop excess and embarrassment that was 1999, Blackout! has a welcome no-bullshit attitude but its ceiling is relatively low: it’s just bars on bars. Erick Sermon’s beats are functional at best, and here’s how I know: the album’s best beat is courtesy of RZA, the keep-you-on-your-toes bass-line of “Cereal Killers.”

Consider Tical 0: The Prequel—awful cover, let it be known—the fall. While he’s quick to blame Diddy in interviews, it’s not like he’s beyond reproach because how else would you explain all the albums he kept churning out afterwards? 4:21... The Day After drops the ‘Tical’ shit and feels like a reset button on his discography in that regard, but the street songs and R&B crossovers (three of these this time, none good) are getting stale by this point. Erick Sermon & Mathematics cook up a piano line worthy of the best songs on Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version for the ODB feature, but “Got To Have It” is one of the most vacuous songs ever, a shopping list of luxury goods that Method Man feels like he deserves, and “Ya’ Meen”—produced by DEEKAY and The Chairman of the Boards, whoever the fuck they are—is just as bad as any of the songs on Tical 0. Meth still rhymes strong occasionally on 4:21 (“It's that Blackout, spazzed out, G-String divas / Leave you assed out, passed out, it's cold / Pack your heat up, blow your back out / You bad mouth, make 'em all believers / Throwing rocks from a glass house” is how he opens “Presidential M.C.”).

Blackout 2 is awful: “And if you dress in the metrosexual way, then muthafucka, you gay” and a ‘retarded’-‘started’ rhyme cribbed (sorta) from that Black Eyed Peas song; songs like “A-YO” feel like crossover attempts that would appeal to neither pop nor rap circles. There are a lot of features from people with annoying voices, not pulling punches there. The rhyming has also taken a turn for the worse: both of these examples are from Redman and from the same verse, “Yo, I’m rolling in my ride, my eyes real chinky / Hit 145, buy like 12 twinkies” and “That n**** too fly / My mama gave birth on Continental Airlines / I ain't lying.”

Having milked the Tical series for all the debut was worth, Method Man pivoted on The Meth Lab trilogy, albums that scream mixtapes with their overstuffed features and concepts inspired by Breaking Bad, replete with enactments of the show’s dialogue. That Blackout (the first one) is Meth’s best (/only good) album besides Tical is proof that he should never have bothered with concepts or crossovers, and just went straight for bars. Of course, that’s also his limitation: bars, bars, bars. And bars that are not as good as the previous three rappers covered thus far.

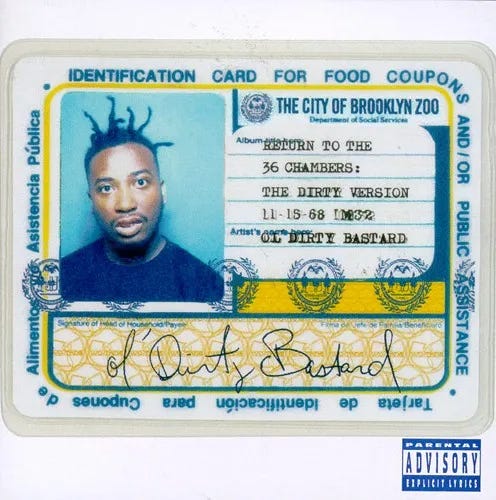

Ol’ Dirty Bastard

Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version was supposed to be the first Wu solo album, and were I RZA, I would not have trusted ODB to deliver it. Case-in-point: he didn’t, and the album was released after Method Man’s Tical. RZA really goes out of his way to tailor his beats to ODB, far more than he does for Method Man. It’s the better album as a result: the piano on “Shimmy Shimmy Ya” and “Cuttin' Headz” is bouncy and deranged to match ODB’s voice; the “We Will Rock You” drum beat lets Ol’ Dirty Bastard come off the page of posse cut “Snakes” (“When it comes 12 o’clock! I turned into the demon beast,” he screams). “Damage” shows a surprising kinship between the lucid GZA and the anti-lucid ODB (“ODB: Can't understand it? Here's the panorama / GZA: A complete view of how I defeat you!”). “Intro” is ab-clenching humor delivered by a strangely haunting vocal performance (“The first time, ever you sucked my dick, uh-ah / Thank you, thank you I felt the earth tremble under my balls”) that reminds me of De La Soul’s “Johnny’s Dead.” It’s an album where greatness arrives in random spurts—there’s nothing going on in “The Stomp” besides that drum beat punctuating his rhymes—but that’s way more than I can say about many of these Wu solo records. It’s a ‘B+’ record that I so desperately want to be an ‘A-.’

N**** Please taps outside production like the other second-wave Wu albums but what’s surprising that Russell Tyrone Jones went southwards towards Virginia Beach and linked up with early Neptunes, demonstrating a musical curiosity that just wasn’t there for a lot of his brethren who kept linking up with RZA-wannabees. “Got Your Money” is a rap-pop crossover that puts a lot of others to shame by not stifling ODB (“I don't have no problem with you fucking me / But I have a little problem with you not fucking me”) while still letting the chorus pop (and what catchy choruses they are); dig the Neptunes’ synth-horn in the second verse reminding you of that indelible melody, and it’s a head-nodder of a bass-line. The rest of the album is not like that (in fact, on the first Neptunes production on the album, ODB spells that out for you: “This ain't no commercial song”), not that I would have wanted it to be. But Irv Gotti & Dat Nigga’s stirring strings of “I Can't Wait” sound like glittery mush and RZA’s horn loop on the title track is an awful sound that unfortunately takes over from the chill vibes of the first minute or so and “Good Morning Heartache” is the sort of eclectic throwback you’d expect from Andre 3000 on Speakerboxxx/The Love Below or Idlewild but it goes on for 2 minutes too long. (Best quote: “I'm a dalmation, knahmsayin? / Motherfucker I'm white and I'm black, what”).

ODB was in and out of prison at this point, and so Elektra Records washed their hands of him by releasing a greatest hits album and fulfilling his contractual obligations. The Trials and Tribulations of Russell Jones appeared in 2002 while he was in prison, made possible by recycling old material and pairing him with strange features (mobb music boss E-40 and Insane Clown Posse), and club beats mostly by some guy named ‘Tytanic.’ There’s a skit about taking a dump, two years before Eminem’s Encore. Better time would be spent listening to the posthumous album A Son Unique even though—again—it doesn’t feel like an ODB album, but rather a feature-loaded album that happens to have a few Russell Tyrone Jones verses that they had lying around. That said, the Misty Elliott and Clipse tracks are worth seeking out, which feel like continuations of what ODB was doing on sophomore.

Masta Killa

The black sheep of the original Wu-Tang family. Elgin Turner was the last to join the Wu-Tang Clan, and he only has one verse throughout their debut album, at the end of “Da Mystery of Chessboxin,’” where I couldn’t pick his voice or flow or lyrical content from a line-up (to be fair to him, it was the first verse he ever wrote), and so I wasn’t exactly rushing to hear his solo albums. (Not helping is that I confused him with Masta Ace, and thought I already did hear them for the longest time.)

Clearly, the whole world clearly had the same mentality: Masta Killa’s debut album didn’t arrive until 2004, a whole decade after Method Man started the wave of solo Wu. Hence the title, No Said Date. Mathematics should have sued Kanye West for flipping Otis Redding’s “Try a Little Tenderness” to almost the same degree on “Otis” as “D.T.D.” seven years later. Even if Turner’s flow has gotten more nimble over the years, the best songs on No Said Date are the ones where other Wu members show (him) up. The obligatory sex song has Turner going “I knew she had the good nook-nook from the first look,” and the closing song named after himself—with its gratuitous Bruce Lee sample over a stock East Asian harmonies—is corny as fuck.

Masta Killa has released three other albums afterwards, none nearly as good. Really quickly: “Street Corner” on his sophomore might be the best deep-deep-deep cut of the Wu-Tang oeuvre, especially when Inspectah Deck layers multiple internal rhymes into two lines (“I was raised by the stray dogs, blazed off, layed off / Breaking laws, graveyard shifting every day war”); “E.N.Y. House” is unmistakably MF DOOM’s beat and no one else’s. But the album ends with a very annoying high-pitched string on “East MC’s” and then a reggae song, both of which eat up too much of the album’s overall run-time. Selling My Soul arrived six years later as a stop-gap release with only Kurupt as the feature to symbolize just how much effort was put into it (what’s noteworthy is that the Inspectah Deck beat for “R U Listening” is the exact same one that appeared on Wu-Block’s “Crack Spot Stories” released one month earlier). Given that, Loyalty is Royalty is far better than you would think, but more than any Wu member I’ve covered so far, Masta Killa is a rapper that is completely at the mercy of his producers, and he doesn’t have the ear (or isn’t picky enough) to choose unique boom bap beats. Case-in-point: the Terry Riley-ish start of “Noodles, Pt. 1” is the best part, and then it’s ditched for generic strings.

Inspectah Deck

Conventional wisdom hypothesizes that if Jason Richard Hunter’s solo album Uncontrolled Substance was released in 1995 as intended, it would be hailed as a classic with the other Wu solo albums. But when a basement flood destroyed RZA’s beats intended for Inspectah Deck’s debut solo album, it was postponed until 1999 andthe beats are supplied by mostly others: Mathematics, 4th Disciple, one from Pete Rock, and a handful from Deck himself. RZA produces two beats, neither good: one with horns and the other with strings, basically, his two default modes post-Forever. (“Friction” also has a vocal sample that sounds like RZA’s copying himself from “Verbal Intercourse”). A few things of note: Inspectah Deck’s beat for “Elevation” will be used by Ghostface Killah on Supreme Clientele’s “Stay True,” and the outro of “Hyperdermix” sounds like the intro to D’Angelo’s masterful “1,000 Deaths.” “Show N Prove” has some decent rhymes (“I was twelve at the time, held .9s, held mines / A frail mind, criminal thoughts well-designed”) and words of wisdom (“In hard times force crimes out an honest man”). On the contrary, I have no idea what he was trying to do on the ‘storytelling’ woman-hating “Forget Me Not,” or what producer V.I.C. was up to either.

Sophomore The Movement states outright that Inspectah Deck wants to “take back the music” but it’s an album of low-stakes boom bap hip-hop that feels—just as Deck criticizes commercial rap for being—watered-down. The soul samples of “City High” and “Who Got It” are pleasant, but they’re practically begging for someone more talented to toy with the samples, and there’s yet another ladies song that falls flat on its face for its embarrassing rhymes from Streetlife (“You go for the street type / Who keep the g tight, and hit the G-spot right”) and Deck (“Your hot like a fireplace, shows in your face / Now, come out the closet, baby girl, it's safe”). In both these cases, Deck doesn’t command attention for an entire hour, which is why I prefer him when he’s sharing microphone time with Esoteric as Czarface, a rap supergroup with 7L producing that actually does feel like a supergroup considering the high-profile collaborators including MF DOOM and DJ Premier.

U-God

When Cappadonna belatedly joined the Wu-Tang Clan, Lamont Jody Hawkins a.k.a. U-God must’ve breathed a sigh of relief: he was their weakest member up until that point. Despite an impressive baritone rumble of a voice, his flow was also lumbering and basic. Solo debut Golden Arms Redemption arrived belatedly in 1999 with very little to recommend it even if it’s not outright bad beyond the lame ‘hard’ hooks (“Dat’s Gangsta” and “Lay Down”). U-God tries to get absurd a la Ghostface/Raekwon on the ironically-titled “Stay in Your Lane” (“Renegade chicks, strap a grenade to my dick / This shit is feather”; whatever) and gets upstaged by Deck on posse cut “Rumble.” More beats from Bink! might’ve helped, with RZA mostly not bothering, which I understand drove a wedge between the two leading to the two eventually parting ways, hence why second album Mr. Xcitement features no help from the Wu family.

The Hillside Scramblers is a failed attempt at creating his own crew, which might have worked if he didn’t out-rap everyone there—I challenge anyone to listen to posse cut “Gang of Gangstas” all the way through without dozing off—and if the beats weren’t all boring early-2000s electropop, a far cry from the music that U-God supposedly would’ve made with RZA. So he promptly linked back up with the Wu-Tang Clan for Dopium, an utterly unremarkable album despite almost every Wu member assisting (notably no RZA beats) that was also so short, he had to pad it out with a bunch of remixes at the end, and with yet another bad sex song (“She nicknamed her breastesses the Wonder Twins / She went to the exorcist it's under skin”).

U-God strikes me as the sort who feels like they deserve more simply because they were at the right place at the right time, which was Staten Island in the early 1990s.

Cappadonna

Cappadonna’s debut album, The Pillage, is better than anyone could’ve possibly have predicted based on his appearances on the Wu-Tang Clan albums or the solo joints up to that point. It’s also not good either: “I drip through the faucet, I never lost it” is how he starts one of early verses and it’s a clear rhyme for rhyme’s sake, and those just keep coming. Follow-up The Yin and the Yang is worse because the beats don’t help him as much, especially when the album reaches its midway point and Cappadonna aims straight for the club. But it’s not convincing before that point either: producer 8-Off taps a weird, wet, dripping sound to loop for “The Grits” whose R&B samples are otherwise the vending machine pap; Ghostface Killah hangs out for “Super Model” but doesn’t bother dropping a verse. Neonek (most of the beats are produced by nobodies, with the exception of one Jermaine Dupri beat and one from Inspectah Deck)’s “Bread of Life” has a good keyboard melody, but it’s absolutely buried in a fussy beat, including gunshots for good measure. Unfortunately, the prospect of hearing any more albums from him elicits a firm ‘Cappadon-nah’ from me.

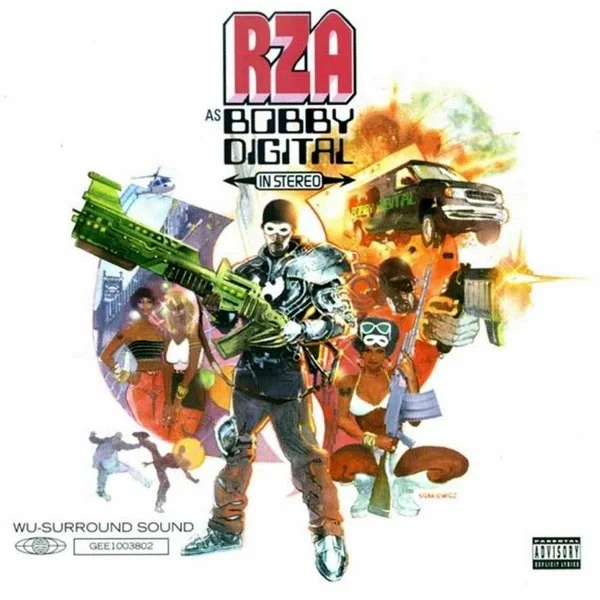

RZA

I mentioned earlier that RZA’s rare appearances on the microphone could actually present an inspired if unpolished rapper that’s far better than some of the ‘real’ rappers of the crew. He does as well as anyone could imagine when he hogs the microphone on his solo albums: he can’t carry hour-long albums, and not like his production skills were intact when he started his journey as ‘Bobby Digital’ in 1998. The failure of RZA as Bobby Digital in Stereo is that at no point does it even try to make you invested in this new persona of RZA’s, or how Bobby Digital is any way shape or form different than RZA in the first place. Primary talents: RZA is a beat-maker, not a rapper. And so when he tried his hand at the latter, the results were predictably lackluster.

Digital Bullet is even worse, where both RZA and GZA sound like they’re sleep-talking through their verses. The production is downright pathetic, including yet another (third time’s the charm, even though the first was best!) sample from Wendy Rene’s “(After Laughter) Comes Tears” on “Black Widow Pt. 2,” or the minimal ‘dance’ track “La Rhumba,” or whatever he was aiming for on “Bong Bong.” The 3-note repeated beat of “You Can Call Me Nick” is lifted straight off of Supreme Clientele’s “We Made It” to the point that I had to check Wiki to see if RZA produced both. (He doesn’t.) Speaking of, it was nice of Ghostface Killah to donate some leftover verses to Jamie Sommers, whoever she is (“Because I see the true reality, sculpted by my Wallabees / Study righteous God Degree” is pure Supreme Clientele). RZA should have been defenestrated for making me listen to his verse on “Shady”: “Girl you can't trick me / Nor can you stick me / You try to play slickly said you strictly dickly / But you and your friends you play the licky licky / I figured it out when I caught that hickey / Between yo' legs where your chocolate split be”).

Released between these two albums is the film score Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, which is supposedly superior to either because RZA (mostly) keeps his mouth shut. But I don’t buy into the album as anything special, and I certainly don’t consider it to be the rare instance of a Wu member trying their hand at anything new: this is just boom bap instrumentals that were created to score a film. The cinematic string line of the first half of “Opening Theme” can be found on every album RZA cut in the past four years or so (the lo-fi, brooding second half is much better, and clearly RZA knew it since he raps over it later on in the album) while “Samurai Theme” could’ve been the backing track for a posse cut on a second-wave Wu album (not a compliment). A major exception: “Flying Birds,” which could’ve been an instrumental from the Ghost Box label if not for the drum machine. Even the free jazz track eventually brings in a boom bap beat. All told, this is not akin to the eclectic beat tapes by J Dilla or Madlib which it sometimes gets compared to.

Naming rappers that suddenly fell off is easy: this page has about a bunch of prime examples, and Eminem is right there to think about. Naming producers is much harder, particularly because they tend to avoid the limelight; Kanye being the obvious exception (and even then, I wouldn’t even say he ‘fell off’; he slid slowly on ye, and then lost his mind). No one fell off harder than RZA, because no one dominated the genre for as long as he did: between the four years of 1993 and 1996, he produced a classic album practically every time he went behind the boards. But then, as mentioned earlier, he cast his gaze towards Hollywood and stopped coming up with any unique ideas in music. He backs up five full beats for The Swarm for the Wu affiliates, but even by then it was clear the well dried up. People kept clamoring for RZA beats on the solo albums but the few that he donated (if any) were so bland that you were better off with one of his disciples which kept mining his sound in better ways than he could be bothered.

2003’s Birth of a Prince is framed as a rebirth—his first studio album to be filed under RZA and not Bobby Digital—but he keeps referring to himself as Bobby Digital throughout. Violent brags like “No caffeine, but the submachine gun will percolate” and “I got two hands but I'm known to carry three Glocks” are funny to me, in a desperately pathetic way. There were a few pop cuts before, but 2008’s Digi Snacks is a heavier attempt at mainstream from someone who should never have left the basement, replete with garbage hooks and feeble drumming (“Try Ya Ya Ya”), and about a hundred features, only one of which came from anyone in the Clan. “Creep” might’ve been an interesting humid-summer beat if not for the lack of space, and Thea Van Seijen tries really hard to be Erykah Badu whenever she’s called upon. 2022’s Saturday Afternoon Kung Fu Theater (with DJ Scratch) and RZA Presents: Bobby Digital and the Pit of Snakes are blissfully short, but they’re all worse than I could have possibly imagined a modern-day RZA solo album in 2022. These are real lines that appear on the latter: “Learn the Dim Mak touch death touch with his cock / He slept with his dick inside a 12-inch sock”; “The Y chromosome is the answer to the question who is the greatest?”; “Would you rather have a smart phone, or a smart child?”

Of course, RZA was involved in another supergroup besides Wu-Tang Clan: Gravediggaz, alongside Prince Paul (of De La Soul fame, and ultimately a far stronger producer), Too Poetic, and Frukman of Stetsasonic. Like Wu-Tang Clan, each adopted a new moniker: Prince Paul became the Undertaker; RZA, the RZArector; Too Poetic, the Grym Reaper, and Frukman, the Gatekeeper.

Their debut album, 6 Feet Deep, dropped in 1994 because despite the classics that Prince Paul had under his belt, he couldn’t get a label to bite until Enter 36 Chambers was released and that violent style was in. The term ‘supergroup’ implies something far loftier than these results though: consider them just four friends, stoned out their minds, and having a few laughs: the first few lines of the album after the brief skit goes like this, “BEE-WAHRE! Four figures appear through the fog / Yeah, Gravediggaz cut like sword - AHHH!” and it becomes very obvious very fast that they’re not taking themselves too seriously, so you shouldn’t either.

That said, the unregal flows of each of the rappers here—including RZA’s—all sound similar, and all sound like put-ons: a lot of exaggerated syllables and quivering tones, like they’re mugging you on the spot and eager to get away. Effective to a point, but wearying over the course of an album. RZA shines the most: his verse on “Graveyard Chamber” displays his love for history while cooking up unique rhymes, “Maintain your order ‘cause once I slaughter / I destroyed a whole city like Sodom and Gomorrah or Babylon / I’m running shit like a marathon.”

Alas, Prince Paul doesn’t bring the psychedelia or colour of those early De La Soul records, going for a lo-fi feel that’s perhaps influenced by RZA. It still leads to great beats here and there: the exaggerated horror-house piano chords of “Constant Elevation”; the see-saw squeak of “Nowhere to Run, Nowhere to Hide”; the blues guitar of “Defective Trip”; the vibraphone of “Blood Brothers.” RZA hands in two himself: the aforementioned “Graveyard Chamber” and the title track, and, predicting the few beats he started turning in whenever he felt like it moving forward, neither are highlights.

The fun is dialed down for their second album, The Pick, the Sickle and the Shovel, and not helping is that Prince Paul is barely there anymore, producing only the outro; RZA similarly also had one foot out the door, hence why neither are involved at all on the third album, which is a Gravediggaz album in name only. The rapping is more sophisticated—Poetic: “You hear the laughter seconds after that you fade out / You're played out, you're laid out, your heart nearly gave out / You're lucky that you made out”—which has paradoxically makes the album feel less unique and special. RZA listing out chemical elements on “Pit of Snakes” has a big Jay-Z on “Monster” energy to it, albeit less endearing.

In 2009, Interpol’s Paul Banks was exploring different avenues outside of his main band, whose career mirrored that of Wu-Tang Clan: critically acclaimed debut and then a slow trickle of albums that sometimes hit that nostalgia spot but ultimately never came close, having started a solo career under the name Julian Plenti where he was doing Frank Sinatra covers in the style of trip-hop. So it kind of(?) makes sense that he linked up with RZA under the name Banks & Steelz, whose one-off album Anything but War dropped in 2016. I don’t think Warner Bros. knew what to do with the album, which doesn’t play like a rap-rock hybrid that you might think: it’s just more of what RZA was up to with Paul Banks’ vocals singing very tired, very tuneless hooks. This segment comes from the lead single, and I guess Paul Banks didn’t have the balls to stand up to RZA and say ‘hey, why are we making this weirdly anti-woman track’ and no one at Warner Bros. bothered to think ‘hey, maybe this shouldn’t be the lead single.’

[Pre-Chorus: RZA] She’s bitchin’ I’m bitchin’ She’s switchin, I’m switchin’ She’s talkin’ I’m not listenin’ I’m bitchin’ bout her in the kitchen [Chorus: Paul Banks] If all is fair in love and war If all is fair in love and war If all is fair in love and war What are you keeping score for?

Of all the rappers in the Clan, it’s actually mastermind RZA that feels like he’s the dumbest, like someone who’s going to start a bad-opinion, bad-vibe, Spotify-only Podcast. And as for his Hollywood career, am I supposed to believe him wearing a suit with the white sneakers combo could hold his own against Tony Jaa?

As I wrote up-top, only an insane person would listen to all of these solo records, especially when half of these albums are not good, not even in the ballpark as good. So you’ll notice I missed a few here and there to preserve my sanity. You know what’s more insane? Writing up 12k words and putting it on a substack for everyone to read for free. No one would be that crazy, would they?