Deerhunter

I was a dream of myself

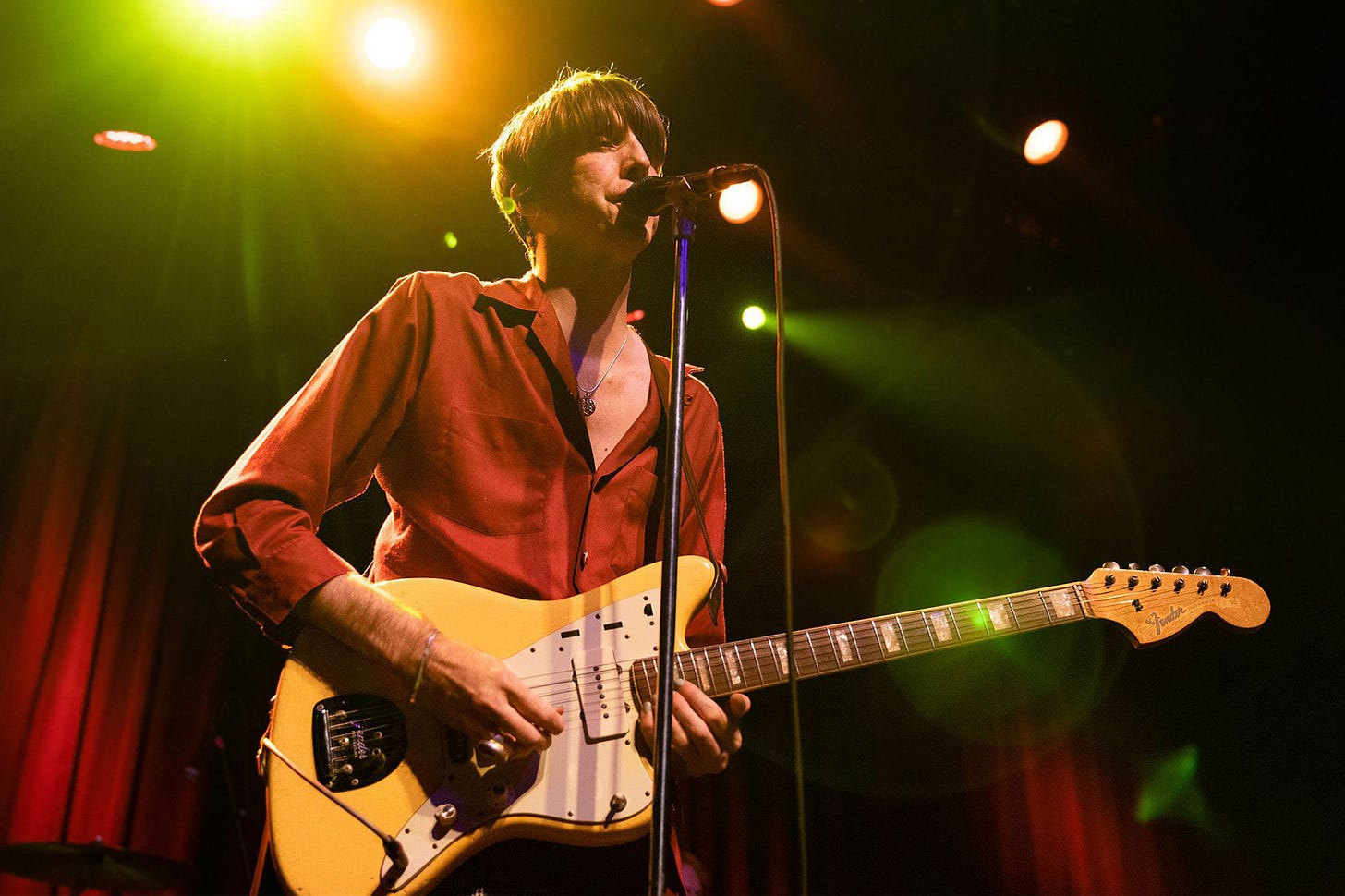

On September 12, 2013, my best friend and I walked out of the Phoenix Concert Theatre after Deerhunter’s set. We both liked the show, but were unsure of just how much. The Atlanta indie rock band had just shifted styles (again) from the daydreamy Halcyon Digest to the guitar-heavy Monomania, the new album that they were touring. Prior to Monomania, the frontline of the band was made up of front-man Bradford Cox and second-in-command Lockett Pundt a.k.a. Lotus Plaza, both of whom played guitars. But for Monomania, they were joined briefly by a third guitarist Frankie Broyles, and the sound was dirtier and punkier, and often reminded me of what I liked to call ‘garage rock revival revival’ (i.e. not to be confused by the 2000s garage rock revival) a la Thee Oh Sees and Ty Segall. I remember the two men leaving in front of us feeling similarly, with one of them expressing outright that they felt Monomania was a disappointment.

In the years of 2012 and 2013, I felt that indie rock as I had come to know and cherish was dying: its core audience was moving on to pop, R&B, and hip-hop, and all of the bands that the internet had hyped from the previous decade were slipping off. Animal Collective released Centipede Hz and was responsible for the worst live show I had ever seen. Arcade Fire released their first outright failure, though they still put on a good show for it. Dirty Projectors, Grizzly Bear, Phoenix and the xx failed to release albums as good as their 2009 masterpieces; the National’s Trouble Will Find Me was their least-rewarding album since pre-Alligator; the Yeah Yeah Yeahs checked themselves out of the conversation entirely. At the time, I lumped Deerhunter in with all of these bands, but in hindsight, Monomania has revealed itself to be their best album, rocking louder courtesy of the triple guitar assault than did the acclaimed Microcastle, while also grooving and glowing with as much twilight texture as Halcyon Digest. Cox certainly agrees,

Monomania is the greatest album I’ve ever made and anybody that doesn’t like it has no idea what I’m about or what I’m doing. They’re simply avid fans of what’s called indie rock and think we’re a notable indie rock band. I hate indie rock and never liked the term. I don’t consider myself a participant in indie rock. I think it’s a ghetto.

Bradford Cox is striking in appearance because of Marfan syndrome—a genetic disorder that makes it seem like the person has been abnormally stretched tall and thin, among other complications—which caused him to look and feel awkward growing up. His gangly physique, and his asexuality and queerness, all manifest in stream-of-conscious lyrics that often deal directly with isolationism, channeled through Bowie-influenced vocals that hiccup, sputter, soothe, and seethe. If he isn’t the best male vocalist of that era of indie rock, then I’m hard-pressed to think a better one. It is why Deerhunter’s music, at their best, felt like it was speaking directly to a select few that understood where he was coming from. It’s also why I think I’ll never be able to write about them as gracefully as spectreview on RYM, which is mandatory reading for anyone interested in the band:

what cemented me to Deerhunter’s music was how that queerness weaves itself naturally into music that is so obviously powered by the alchemy of the inner voice. Deerhunter and Atlas Sound records have been described by many as psychedelia – a term that Cox actively rejects in regards to his own music – and I find the label sticks not because of any association with the genre’s hammy origins but because of its invocation of the developmentally-arrested psyche. Or, to be more specific, its portrait of the damaged feedback-addled psyche, of which a thoroughly-repressed individual could innately understand.

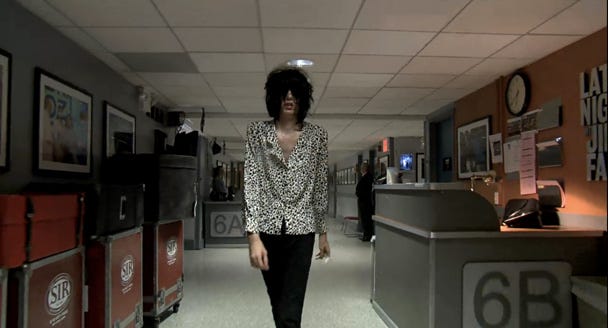

Cox was also caustic in interviews and even in live performances in a way that was shocking and memorable. He performed “Monomania” on Jimmy Fallon in a ghastly wig and with his left hand prominently bandaged, and, when performing as Atlas Sound, upon receiving a request from the audience to cover “My Sharona,” he proceeded to launch into noise terrorism that lasted an hour. Interviews are loaded with soundbytes that are honest, humourous, and altogether engaging on a level that was frankly radical at the time compared to any other indie artist. Here are some of my favourites quotes from Cox:

“If you’re going to tell me someone like James Blake is the new David Bowie, I’m going to shoot myself in the head.”

(In response to the “My Sharona” incident) “I am terrified and horrified and shocked that anyone would mention Phish in any article related to me.”

(In response to being asked about the aftermath of Microcastle’s success) “Everyone was still alive. We were relatively young. We were also miserable and moving toward the negativity that awaited us.”

For another great overview of the band, I recommend checking out Chris Deville’s article on his Such Great Heights substack which pulled me out of a month-long writer’s block anrompted me to write this one in the first place. I agree with Deville’s assessment of Deerhunter’s status as one of the best indie rock bands of that era, “They were master world-builders, attuned to every little detail—versatile enough to build propulsive momentum or slow down into a lurching swoon, fearlessly vulnerable yet alluringly oblique, masters of atmospherics but not at the expense of sharp songwriting.”

Indie music of Deerhunter’s era—made by and made for “hipsters”—was obsessed with nostalgic for an era when alternative actually meant alternative and when independent actually meant independent, and when it was actually cool to be either. Sonically, Deerhunter’s music reminds me of R.E.M. and Stereolab—notably, albums from both are among Cox’s favourites—with a touch of krautrock, shoegaze, punk, and post-punk, but it also sounds like none of those things because they blended it into their own little soundworld. Which is why I think they were far nobler than many of their contemporaries that kept serving up a cheap imitation of a bygone sound with no distinct fingerprints of their own.

Cryptograms was received to some acclaim, including Pitchfork’s coveted Best New Music stamp, and I fail to see anything worthy of it at all. I truly mean that: the leap from their debut Turn It Up Faggot to this is noteworthy, but the jump in quality from this to Microcastle is astronomical. You can tell that the band is trying to do more than just be your bog-standard indie/post-punk rock band, but they do so mostly through applying generous reverb everywhere which lets them get away (not really) with the fact that there’s nothing going on underneath. The title track gets noisy and “Red Ink” gets quiet in ways that make me think of better artists. Bassist Josh Fauver does his best to carry the band on his shoulders but they gave him no map. For example, Fauver hooks listeners into “Octet”’s swirl, but then all the song does is swirl endlessly for eight minutes, and while I respect Cox’s desire to make “something that was a little more like a landscape,” no images come to mind.

Microcastle might have been their greatest record if not for the medley in the middle that tries to imitate the hauntology of Boards of Canada, Broadcast, or the various artists of the Ghost Box label, but ends up sounding like generic 4AD, although I suppose it’s commendable that an indie rock band would try that style. It’s a shame because the material around it ranks among their best. The shoegazy-psychedelic opener “Cover Me (Slowly)” that transitions masterfully into the sweetly-sung hook of “Agoraphobia,” which was originally written by Pundt intended to be an instrumental, but whose lyrics were written by Cox, and it shows: “Feed me twice a day / I want to fade away, away” is Cox at his most pleading and vulnerable. “Nothing Ever Happened” is a fan-favourite banger held together by Josh Fauver’s elastic and relentless bass playing. I actually prefer “Saved by Old Times” that follows, indie blues whose middle passage—“WE WERE TRAPPED IN THE BASEMENT OF A MOTHERFUCKING TEENAGE HALFWAY HOUSE!”—is actually slightly terrifying thanks to the additional effects applied to Cox’s voice that makes it sound like an old home video that leads into the sweet relief of the hook: “I was saved by old times.” “Twilight at Carbon Lake” may be simple in sound and swell, but the chords do deliver upon the elegiac promise of its title.

Halcyon Digest saw this shoegaze/post-punk blending band turn to indietronica, and the results are immersive thanks to the shimmer of the keyboard and guitar, as well as the thoughtfully textured drums all thanks to producer Ben E. Allen, responsible for Animal Collective’s then-recent embrace of pop on Merriweather Post Pavilion. The album is structured such that the near-7-minute “Desire Lines” is the centerpiece: an ear-worming song featuring Deerhunter in straight-up anthem mode. My hot take? The song sucks. I was not surprised at all to read that Cox had nothing to do with the song as Ben Allen removed him from the studio, because it doesn’t sound like anything he would ever write. It’s Coldplay for people who think they’re too good to listen to Coldplay.

The major highlights are, instead: “Helicopter,” about human trafficking victim Dmitry Makarov (“Oh, these drugs, they play / On me these terrible ways”), “Coronado,” thanks to Bill Oglesby’s shronking saxophone feature that gives the song an ugliness worthy of David Bowie’s Scary Monsters, and, especially, the Jay Reatard tribute closer “He Would Have Laughed” where the lyrics and the way the groove ends makes it feel like trying to remember something that’s no longer within your grasp (“I lived on a farm, yeah / I never lived on a farm”). The shorter tracks scattered throughout help the album flow, especially the humid atmosphere of “Basement Scene”—recorded in an actual basement, and it sounds like it; it’s a very weird lo-fi track on an otherwise immaculately produced album—and the militant-but-sad “Memory Boy” whose lyrics feel intensely autobiographical (“Try to recognize your son / In your eyes he’s gone, gone, gone”).

Rather than write “Little Kids” or “Desire Lines” over and over again for an audience he would later feel never understood them, Cox led the band into their loudest and most abrasive phase for Monomania. The first song of the record is called “Neon Junkyard” and that’s what the album sounds like as there’s actually an orange glow to these songs that makes them feel special. The guitar riff of “Pensacola” is scuzzed out but hopeful as Cox lays out his asexuality-queerness plain for all to see (“Well, I could be your boyfriend though I could be your shame”) with a chorus that’s their bluesiest ever. “T.H.M”’s guitar arpeggios are simple and dreamy, laying the foundation for one of Cox’s scariest songs but I never hear any praise for it; the way the microphone distorts when he sings “My head was like a WOUND” is basically a jump-scare in a song like this, and the band turning it into a 3-guitar assault when I watched them live was the most memorable part of the set. “Back to the Middle” expunges heartbreak by essentially grooving it out, the notion of being “back to the middle” is annoying for Cox given how he shouts it out, but you know he’ll pull through. There’s so much on the record to love, I’ll always surprised people stump for the title track which might be the simplest one.

Best of all is penultimate-shouldabeenthecloser “Nitebite.” The track is tender and barren, allowing listeners to realize just how special Cox was as a vocalist as he sings in irregular jumps and spurts, smoothing out sad thoughts with gorgeous flights of falsetto, “I was a dream, a dream, a dreammmmmm of my self / I was no longer in good health, hmmmmmm”—genuine question: is this the most soulful vocal from all of indie?—backed only by acoustic guitar and the occasional drum beat (the one that harmonizes with his spit at 0:45?). The song really does feel biking out to the suburb’s end, reflecting on an entire summer of loss and wondering if it’s worth it to endure another if it’s just going to end up the same.

Fading Frontier sees the exit of briefly inducted third guitarist Frankie Broyles and the reunion with Halcyon Digest producer Ben H. Allen who had since become The Man Who Gave Us Washed Out. Regrettably, “Living My Life” and “Take Care” and even the drum sound of the otherwise atmospheric “Ad astra” are exactly what indie types thumbed their noses at for years: shopping mall music. The highlights are retreads: “All the Same” is as good a return to Microcastle as we could’ve gotten seven years removed, and I like the way Bradford Cox spits out “S-s-s-you should take your handicaps / Channel them and feed them back...” even if it just makes me think of the Strokes’ “You Only Live Once”; “Breaker” is just a re-write of “Dream Captain” with all the gristle and sinew removed. But that’s off-set by songs that are, for the first time in Deerhunter’s career, lame, especially when they get ‘funkeh’ on “Snakeskin” or when Bradford Cox leverages the phonetic coincidence between “Carrion” and “Carry On,” which is not that far removed from Arcade Fire’s Win Butler going “Infinite content are we infinitely content.”

In an interview with NOW Toronto magazine Bradford Cox called Fading Frontier and its follow-up “way more frightening and strange than our early work,” and it certainly is frightening and strange that talent could just disappear like that! The problem, I reckon, is that Cox sounds happier on these records, but Deerhunter were fundamentally an unhappy band to an almost unhealthy degree, and he’s trying to have it both ways on these records. On Fading Frontier’s “Living My Life,” he sounds blissed out as opposed to blissful. On Why Hasn’t Everything Disappeared Yet?—low hanging fruit, I know, sorry not sorry—cuts “Death in Midsummer” and “What Happens to People?”, doleful lyrics are set to bright harpsichords and piano chords co-produced by Cate Le Bon (still waiting to hear any album with her production that doesn’t sound lifeless) respectively that makes the imagery muddled if not plain nonexistent.

Not helping is that Cox is not a great lyricist, but it was not a big issue at all when he was sputtering and seething his lyrics on Deerhunter’s early records, whereas on these two albums, he’s singing them plain, which only highlights how is unable to plumb the same lyrical territory as R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe. “Death in Midsummer” reminisces “They were in hills / They were in factories / They are in graves now” in a way that recalls R.E.M.’s “This is where we walked / This is where we swam / Take a picture here / Take a souvenir” from the masterful “Cuyahoga.” Elsewhere, Cox misinterprets an R.E.M. lyric from “Green Grow The Rushes” for “Living My Life,” but Stipe put together interesting turn-of phrases like “Amber waves of gain” and Cox can’t imagine out of place words like that, so he thought it was “Amber waves of grain,” never mind that he had no idea he ended up quoting an American patriotic song instead. Meanwhile, he nabs ideas from Gary Numan for “Greenpoint Gothic” and Laurie Anderson for “Détournement,” both unfulfilling pastiches that play out like a fatal lack of ideas, which likely explains why the band hasn’t released an album since.

That’s their core discography. There’s two EPs. Fluorescent Grey is probably made up of cast-offs from Cryptograms but I like the repetitive krautrock-esque brood of both the title track and “Wash Off,” and I’d rather listen to either than anything from the actual album, although I found the two pop-structured songs in the middle unconvincing, like they were testing the waters for Microcastle but hadn’t quite figured it out yet. Rainwater Cassette Exchange is made up of 5 short songs released in 2009 as a stopgap release between Microcastle and Halcyon Digest, with “Disappearing Ink” and “Circulation” feeling like garagey rockers that would have made no sense on the latter and so packaged up here with a few other tracks of no consequence.

Microcastle was leaked months in advance, and frustrated but not as much as Nas circa 1999, the band cobbled together Weird Era Cont on the quick and packaged it as a bonus disc (ironically, it would also be leaked). “Operation” comes early to trick you into thinking there’s more good songs to come, and then you’re met with many go-nowhere instrumentals; “Vox Humana” is a poem (more of those isolationist lyrics) set to “Be My Baby”’s beat; “Focus Group” is basically “Never Stops” with everything good about it removed. A lot of people seem to like “Calvary Scars II/Aux Out” because…it’s long and has a crescendo? I’d recommend just skipping this one completely, but at the same time, I think the band making it at all was a thoughtful idea, and honestly one that should be talked about more in regards to an artist going the extra mile for their audience because they felt like they deserved it.

Better yet is Double Dream of Spring, a mostly instrumental cassette tape that was on sale during the band’s Spring 2018 tour which sold out immediately. Whereas Weird Era Cont contained many songs that felt like solo bedroom noodling that Cox felt weren’t good enough for his debut album as Atlas Sound, Double Dream is a full band affair, and so the experiments like the bass-heavy “Lilacs In Motor Oil” and playful “Faulkner’s Dance” are far more fulfilling. Best of all is “Dial’s Metal Patterns,” which starts like a late-60s psych-romp that develops into an extended solo from new member Javier Morales who joined the band in 2016 that plays like a krautrock tribute. It’s frankly the band’s best song that they cut after Monomania, and it’s a shame only the most devoted of fans have heard it.

Turn It Up Faggot - C Cryptograms - C+ Fluorescent Grey - B Microcastle - A- Weird Era Cont - C Rainwater Cassette Exchange - B- Halcyon Digest - A- Monomania - A- Fading Frontier - B- Double Dream of Spring - B Why Hasn't Everything Disappeared Yet? - C