Radiohead

scrolling up and down, I am born again

Radiohead’s core achievement was that they cast their net wide in terms of influence. Their name is a Talking Heads reference, and David Byrne’s method of lyricism for Remain in Light inspired how Thom Yorke approached the words on Kid A. Nigel Godrich’s clean, digital production is a direct descendent of Brian Eno’s style, from whom they nab a melody for “Videotape.” They’ve also taken a Beatles chord progression for “Karma Police.” The chaotic jazz tracks of Kid A and Amnesiac are inspired by Charles Mingus. Yorke’s twitching shamanism traces back to Can, whom they covered extensively on tour, and their downcast mood traces back to R.E.M. Their switch from alternative rock to electronic was inspired by Warp acts like Aphex Twin and Autechre, as well as watching Underworld perform. I know no other band that functions as much as a gateway into so many other bands and even me genres as much as Radiohead does. I’d like to think they brought a musical curiosity into the 2000s that was sorely needed in alternative rock.

I had heard every album from The Bends through In Rainbows about 300 times apiece according to my university Itunes, but this was before I discovered blogspots, sharethreads, mediafire links, and torrents. RIP to basically all of those things. So know that this very long and often very critical write-up comes from a place of deep historical adoration. I don’t listen to them at all anymore. I eventually backtracked and listened to those aforementioned influences, many of whom just did it better. I didn’t know what jazz was prior to me listening to Radiohead, and now I can’t listen to their jazz songs after having heard the source directly. Similarly: why would I ever need “Treefingers” when “[Rhubarb]” is right there for me?

More importantly, I no longer identify with the band’s limited worldviews. Yorke is a great singer: he has a tremendous vocal range, and he’s got the physical power that makes their ballads feel emotionally potent, which is not true of any of their contemporaries with the exception of Muse’s Matthew Bellamy who doesn’t sound like Thom Yorke anyway — the Muse-Radiohead comparisons have always been so incredibly stupid. But Yorke is limited as he whines against a world that he finds deeply, personally unfair, which is the worldview that I’ve personally grown out of.

Ignore any attempts to claim debut Pablo Honey as “not that bad.” I find it altogether unlistenable as so much alternative rock from that era. Even “Creep,” the enduring hit that both the band and fans frowned upon for so long but slowly let themselves like is lyrically repulsive to really hammer home the creepiness. “Your skin makes me cry” —> eughhhhh, sure, dude. The guitar crunch and Yorke during the bridge are both physically bracing, of course. That song, along with “You” and “Stop Whispering” are the album’s peak, so it blows its load early on. “Anyone Can Play Guitar” makes me laugh during the choruses, which I don’t think was the intention. “How Do You?” makes me cringe, which is a far worse reaction. Closer “Blow Out” mixes bossa nova drumming with shoegazey guitars, but not in a particularly noteworthy way except that it’s doing those things. Released near the start of 1993, the album thankfully avoided the Britpop craze which was about to take effect with the releases of Suede’s debut (March) and Blur’s Modern Life is Rubbish (May).

The Bends is loud and flabby like most mid-90s alt rock that was popular on either side of the ocean. It should not be considered a highlight of 1995. It’s hella inconsistent too, peaking with the two big ballads and occasionally getting downright embarrassing in some aspects. The megaphoned whisper-spoken “I wish it was the 60s, I wish I could be happy” bit on the title track as the band tries to interpolate slight trip-hop influence with the Led Zeppelin-esque drums and slow-drip piano that feels like it was grafted in from “Talk Show Host” gives me nightmares. Meanwhile, low-hanging fruit since Yorke himself hates the track, but “High and Dry”’s choruses align them far too closely with Britpop that the album otherwise mostly sidesteps (again, except for the loud and flabby mix). “Sulk” is typical 90s’ defeatism that feels like a leftover from Pablo Honey and the line “You look so pretty when you’re on your knees” is surprisingly sexual for a band as disinterested with the human body as Radiohead are, so of course they de-sexualize it immediately. “I call up my friend, the good angel / But she’s out with her ansaphone” from “Bones” might be Yorke’s flat-out worst lyric.

It’s really a mixture of Thom Yorke’s vocals channeling Jeff Buckley and Jonny Greenwood’s guitar (reminiscent of Blur’s Graham Coxon and Suede’s Bernard Butler except he outclasses both) that carry this album. Greenwood used to get a lot of physical weight in his guitar solos that, yeah, it actually is a shame that they started rocking out less and less. Ed O’Brien does what he does, but the rhythm section often feels deliberate, to the verge of mechanical. Selway never cuts lose, which makes their groovier songs and loud rockers that they essay from time to time feel like the band as a whole is always holding back. All this to say, for a rock band, they rarely really rock. In theory, swapping him out for Tom Skinner—Sons of Kemet and Floating Points—should have helped them rock more as the Smile, proven out by first single “You Will Never Work In Television Again,” but ultimately that band just sounds like Radiohead-lite.

There’s the obvious example of Thom Yorke pouring himself into the release of “Street Spirit,” like an open-armed embrace to everyone in the rain while the R.E.M. trademarked arpeggiated Em/Am chords sound better than R.E.M. themselves did on Automatic for the People. (The album cover looks inspired by the single cover of R.E.M.’s “Nightswimming.”) Elsewhere, Ed O’Brien’s effects in the second verse of “Fake Plastic Trees” makes Jonny Greenwood’s loud entrance—the crunch of “Creep” sustained—feel natural in a torch ballad while Yorke’s flights of falsetto are among his best melody-making.

Those are the two big highlights, but I have never heard enough praise for “(Nice Dream),” maybe because it doesn’t stack up against those two: it’s lovely, and learning that it’s producer John Leckie’s attempt at making an alt rock version of “My Sweet Lord” makes sense given the lullabying backing vocals and strings. And there’s plenty of other good moments that I haven’t mentioned in the other songs! The bridge of “Bones,” meaning nothing but soaring appropriately as Thom Yorke invokes Peter Pan; Greenwood’s guitar on “Just” and Yorke having fun by seething out the words; how disdainful the band is of previous hit “Creep” on “Iron Lung,” from the obvious “This, this is our new song / Just like the last one, a total waste of time” to the interpolation of that song’s aforementioned crunch. But it all sounds too much like early Suede without the glam for me to take seriously, and I prefer their future albums where they lean less on Greenwood and start sounding like a more democratic band, which is a problem I have with most alternative rock a.k.a. Britpop from that side of the ocean around this time. It’s all just guitar and vox, with often no thought given to the rhythm.

OK Computer is their masterpiece. It’s where the band’s ambitions don’t outpace their abilities, and Nigel Godrich’s production is hyper-modern whereas their previous two albums are relics of the 90s. The opening measures of “Airbag”—densely packed with distortion-supported drumming, deliberately cut cello that feeds into the guitar—feels like being transported into a computer, and it’s okay, not scary at all, just part of our now everyday reality.

In that regard, the album feels strangely prescient, especially as the clean electric guitar lines of “Let Down” feel like watching globalization in motion from the airport window, or the ending of “Paranoid Android” which feels like surveying an increasing disaffected generation (“The yuppies networking”) at the turn of the millennium with equal parts paranoia and disgust (“The panic, the vomit”) and hoping the rain just washes it all way, or the ending of “Karma Police” which makes good on the promise of “Buzzes like a fridge” by sounding like a computer digitally erupting, or how Yorke predicts our phone-addicted culture on the opener, “Scrolling up and down, I am born again.” The album feels culturally important in a way that none of their other albums do, with the possible exception of Kid A.

The weaker songs are all in the second half. Without Ed O’Brien’s injection of atmosphere, “Lucky” would be painfully generic in chord progression though there is that one key moment where Thom Yorke takes a long pause after “It’s gonna be…” and concludes, “A glorious day” that tries to rank as life-affirming as “Street Spirit.” Ten years later, the band would extract the best part of “The Tourist”—the melody at the 0:23 mark—and expand on it for “Nude” (the “You go to hell” line) but I keep the song around because the lines, “Hey man, slow down / Idiot, slow down,” links the album cyclically to its opener, “Airbag”’s “In a fast German car, I’m amazed that I survived / An airbag saved my life.” (Apparently the band spent an entire day deciding on the finalized tracklist, and it really shows; not just in the opener and closer, but the whole thing really works as a cohesive unit, in a way that The Bends definitely did not.) I know people have qualms of “Fitter Happier” and “Electioneering,” but the former is two minutes, I think we’ll all live, and I like the atmosphere, and the latter is a shot in the arm when the album needs it most. Of the second half, the best song is “Climbing Up the Walls,” the spiritual successor to the horror-thriller songs from Peter Gabriel’s third album that even Gabriel never looked back on.

“No Surprises” is the one I didn’t mention of the second half, and it’s lovely, sure. But—as I mentioned in my Vampire Weekend write-up—the throwaway line “Bring down the government / They don’t, they don’t speak for us” irks me to no end. It doesn’t relate to any of the lyrics around it. It’s a pose. It’s simple to the point that it doesn’t warrant a second thought. It has tricked people into thinking that this band was intensely political—hence why so many people felt deeply upset by Yorke and Jonny Greenwood’s recent apathy—but that’s just not true: this band was never a political one. Hail to the Thief is less a commentary of George W. Bush than it is just a Bush-era album, and Yorke tweeting lyrics of his songs as a response to recent presidential elections is not meaningful, it is just vibes.

Kid A is impressive in the sonic world it creates, which I’ve come to associate with its cover, all cold glaciers under cracked red skies. That, and the fact that a rock band would abandon guitars to this extent, and the results not be stilted, dated, or flat out embarrassing, is commendable. But it’s grown off of me the most of any of their albums. As mentioned, I don’t get anything out of “The National Anthem” anymore because the brassy jazz sections just make me want to listen to Mingus directly, although that simple, rattling bass-line loop lives rent-free in my head, as does the pinched way Yorke sings “Everyone around here”; nor do I get anything out of “Treefingers,” which is secretly the album’s most guitar-heavy track since it was entirely composed out of Ed O’Brien’s guitar and not actually synthesizers, which it sounds like. “Optimistic” always felt like it wandered in, like the band felt they needed a bone so fans wouldn’t be too put off by the switch in sound, and though the song is totally fine, I feel like the album would’ve only been improved if they scotched it entirely and replaced by one of the more experimental ones on Amnesiac.

But I also don’t get anything out of the lyrics here, which feel like they were composed by pulling them out of a hat, which is actually what happened on the title track. Altogether there’s a lot of “repeat this lyric 5 times” method for verses that ultimately doesn’t bear repeating: the “sucking on a lemon” bit of “Everything in its Right Place” feels like a meme; the “cut the kids in half” bit of “Morning Bell” is where I zone out of that song. The beloved “Motion Picture Soundtrack” would be utterly nothing if they performed it on acoustic guitar, which is how it was conceived back when it was first written during the Pablo Honey era — it’s truly the ditching of the guitar there that makes the song any good. The only two songs that I’ll truly miss if I never heard again are “Idioteque,” where the band’s interest in electronic music actually gives us a beat that’s danceable, and “Kid A” where Thom Yorke’s distorted voice adds to the weirdness. “We’ve got heads on sticks.” That’s fucking weird! That’s the weirdest song on this supposedly weird album, and I’m always shocked some people don’t like it.

Amnesiac was recorded in the same sessions as Kid A, but you would never know if the band never told you: Amnesiac is as much a world onto itself as their other albums. So any time I read someone claim that these are just Kid A b-sides, my eyes roll to high heaven. Because the songs are weirder, the results are more eclectic than last time: I like this album’s twists and turns far more than the more uniformly cold atmosphere of Kid A. “Pyramid Song” is a ballad inspired by Charles Mingus’ “Freedom” which is followed by an Autechre-type abstract beat repurposed into one of their most far out electronic experiments. Trusty alternative rock centerpiece “I Might Be Wrong” is followed by a Johnny Marr tribute in “Knives Out.” Two-minute electric guitar-led instrumental “Hunting Bears” drops you into “Like Spinning Plates” where the glitchy synthesizers makes it feel like a CD skipping and a genuine mistake until Thom Yorke finally comes in. (The piano ballad version on first live album I Might Be Wrong: Live Recordings is a really boring rendition. It’s like if you gave the lyrics to Gary Jules and asked him to write some piano around it.) And on and on the album goes with its hard pivots until closer “Life in a Glasshouse” folds in jazz as did “National Anthem” before it, except, in my opinion, way better.

I like all of these songs, even “Hunting Bears,” which always struck me as very weird specifically because it is so guitar heavy on these two albums that otherwise ditch guitars; it plays like a robot learning how to play electric guitar, its metal fingers sliding across the strings, stopping briefly to see if it got the riff right, and then starting again. “Knives Out” was performed to Johnny Marr before the album’s release, who was moved by it, “I was beyond flattered and quite speechless. It’s truly the guitar-work that makes it special, certainly not Thom Yorke’s typically dour ‘Yorke-isms’ (“If you’d been a dog, they would have drowned you at birth” — yawn), and learning to play the song on acoustic guitar and its subtle variations from verse to verse helped me appreciate it more. It jangles, yes, but each iteration manages to jangle a little differently. The first half of “You and Whose Army?”—sampled endearingly by the Roots in a few years’ time—is a ghost choir practicing their harmonies in an empty church while the second half reframes the title’s bluff as an actual threat; not since “Exit Music” has Phil Selway sounded this physical powerful. Worth stating is that Amnesiac did spawn its own b-sides, the best of which is “Cuttooth” which would have made it onto the album if the role of upbeat rocker wasn’t already covered by “I Might Be Wrong.” Consider this album Kid A’s younger, more introverted, quieter brother. He has a lot to say, if only we’d listen.

Hail to the Thief is when Radiohead ‘consolidated’ their two modes: alternative rock sound of the 1990s with their Warp-influenced reinvention of the early 2000s. The album is programmed so that a multi-guitar assault is followed by purely electronic song (tracks 1, 5, 6, 9, 12) or vice versa (tracks 2, 4 and 8), interspersed by the occasional ballad (tracks 3 and 10), which is to say, it’s less integrated than one would hope. At 14 tracks long, Hail to the Thief contains more songs than any other Radiohead album, and given playlist culture, a lot of people have predictably torn it apart. Understandably, somewhat: there is a fair amount of filler, but the charge that this album is too long is just brain-dead, because it runs only 3 minutes more than OK Computer. It’s just uneven.

The template as always is R.E.M. If OK Computer was their Automatic for the People and Kid A their Up, then consider Hail to the Thief their Lifes Rich Pageant. Beyond similar images of bunkers (“Underneath the Bunker” vs. “I Will”) and falling skies (“Fall On Me” vs. “2 + 2 = 5”), Hail to the Thief and Lifes Rich Pageant were their respective artists’ most political albums, this one written during Bush and 9/11 and R.E.M.’s written short after Ronald Reagan’s re-election. The politics throughout Thief are vague to be sure—only on “Sail to the Moon” does it come to a head—but definitely successful enough in evoking the paranoia of living in the early-2000s in America, and that lends to them making most charged and most poignant rock songs they ever wrote in “2 + 2 = 5,” “Go to Sleep,” and “There There.” (All three of these were released as singles, which adds to the uneven feeling.) I’d rank all three of these songs very highly in the context of the band’s best ever songs, though I’d recommend the live versions performed at Glastonbury that same year and not bothering with Hail to the Thief (Live Recordings 2003-2009); such a treat to see most of the band take up the drum parts on “There There” or Jonny Greenwood cutting loose on “Go To Sleep.”

“2 + 2 = 5” (its Orwell-referencing title forever sealing the fate of Muse being compared to Radiohead) accomplishes a great climax in only a 3-minute run-time as Thom Yorke’s lyrics get wordier and his voice gets more and more anxious, as the backing vocals help sell the Greek choruses of “But I’m not” and “Maybe not.” “There There” has my favourite Jonny Greenwood solo, though I feel a bit dirty saying that since most Radiohead fans I know prefer a different, more complicated Greenwood solo. It’s simple, sure, but the seismic shift from buzzing high notes to the shronk afterwards is great, and it fits the song perfectly, leading the charge out of the bridge and then blending back in with Thom Yorke’s “We are accidents waiting to happen” coda. Elsewhere, Phil Selway—never a complicated drummer—does these occasional fills that are, again, simple, but exactly what the song needs from him.

Equally as good is “A Wolf at the Door,” where Thom Yorke doesn’t even try to sing the verse and the results are the paranoid ramblings of a street protestor over slow guitar arpeggios that imitate organs. Taken out of context, some of these lines read meaninglessly and are easy to pick on, so know that I don’t pretend to care about the “Flan in the face” bit, but I certainly do think “Walking like giant cranes” and “City boys in first class don’t know we’re born at all” are powerful lines. Love the delivery of “Turn your tape off” as if the narrator can’t take it anymore, and how, in the final instance of the chorus, Thom Yorke just resigns: “I’ll never see [my children] again if I squeal to the cops / So I just go—,” launching into a wordless, soulful falsetto and leaving the thought hang in the air as the record finishes.

The electronic songs—“Sit Down. Stand Up,” “Backdrifts” and “The Gloaming”—are second drawer to the rock songs but that’s perhaps expected: Radiohead have always been a better rock band than they were an electronic one. “Sit Down. Stand Up” has a similar structure to the preceding song, and the climax of a voice repeating “…and the rain drops” over the electronic beat is a great moment, and the sort that you can imagine Thom Yorke losing himself to on stage live in that twitch-dance he does. “The Gloaming” isn’t a track I seek out often, but there’s an undeniable eeriness to it as the drums sound like the click of insects at night, but I don’t really get why the song was such a live staple for them.

Some second-drawer material holds the album back. “We Suck Young Blood” is a dirge that has one good trick, the sudden double-time free jazz section in the dead middle, but it’s a trick that doesn’t last long enough to justify the full song which is almost 5 minutes (it honestly reminds me most of the Replacements’ “Favorite Thing” in that regard), while “Myxomatosis” coasts on that bass-line, and Yorke’s emotional disturbed person imitation leaves a little to be desired. I s’pose no one needs the wartime lullaby “I Will” but I’ve always had a sweet spot for it.

In Rainbows marks the first time since The Bends where they make a record full of accessible pop/rock songs, and because Nigel Godrich wasn’t involved until the late stages of the album’s creation, there isn’t the extra bombast of their preceding records. It’s surprisingly hushed and dream-like after “Bodysnatchers,” and this, comfy in a consistency that Hail to the Thief did not have. That said, I would have moved “Bodysnatchers” to the collection of outtakes released soon after where it could’ve joined “Bangers + Mash” as an intense rocker that simply didn’t belong here. My hot take: if it weren’t for those backwards loops on “Videotape”—whose melody is lifted from Brian Eno & Harold Budd’s “Not Yet Remembered”—I’d be totally unconvinced. The invocation of Mephistopheles doesn’t come off for me, especially if you get rid of the Faust reference — “Faust Arp” is the least memorable song here because Thom Yorke simply will not stop singing about “Duplicate and triplicate.” “You’ve got a head full of feathers” feels like a “For a minute there, I lost myself” that’s not nearly as affecting.

The album’s best song is “Reckoner,” where Selway’s drum smacks leave a shimmer, like sidewalks after rain. That bridge—“Because we separate like ripples on a blank shore”—is the most impressive thing they’ve done post-OK Computer, especially in how Yorke seems to float over those harmonizing ghost vocals. It genuine does feel like watching a ripple in slow motion, slowly gaining traction with the stir of the strings, leading back to the verse in a way that I find beautiful.

As Ed O’Brien has said, “[The lyrics] were universal. There wasn’t a political agenda. It's being human,” and so Yorke’s words arrive mostly unfettered with extra stuff. “I’m an animal / Trapped in your hot car” (“All I Need”), “I don’t want to be your friend / I just want to be your lover” (“House of Cards”), “You are my center / As I spin away” (“Videotape”). It’s the most touching album by a mostly touching band.

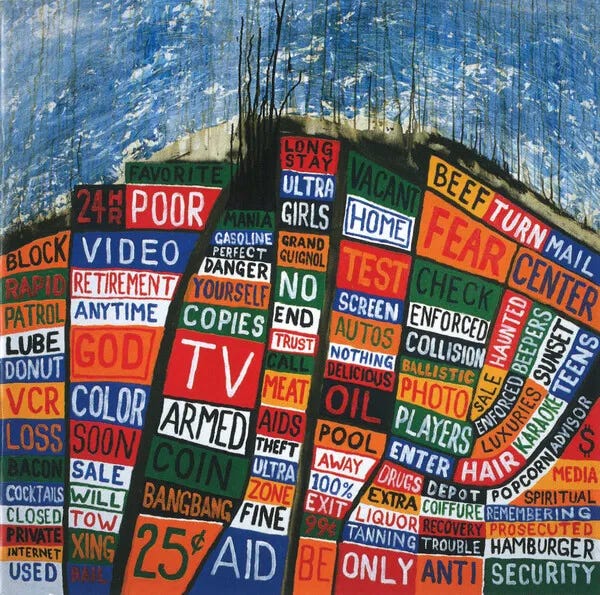

The King of Limbs was received with much confusion that seems humourous in hindsight. With only 8 songs spanning 37 minutes, it is easier the shortest Radiohead album, and there was a feeling of ‘that’s it?’ leaving some fans to speculate that there would be a second part, an Amnesiac to this album’s Kid A. “‘Separator’ separates the two discs!” so claims the conspiracy. (In music, there are no crazier conspiracies than the ones that Radiohead fans make up. The most insane one was that by interspersing the songs of OK Computer and In Rainbows—both albums have 10 letters in their titles, don’t you see? And they were released 10 years apart, don’t you know?—you’d wind up with OK In Computer Rainbows!) No surprise that we didn't get a second disc. What we got instead was a remix album—the best remix, Jamie xx’s “Bloom Rework Part 3” during his ascendancy away from his band doesn’t appear on that compilation—as well as another Live From the Basement set and four non-album tracks in the “Supercollider” and “The Daily Mail” singles that only raised more questions as to why they were not included in the proper album since clearly there was room for them, especially the latter which beats out almost all of these songs.

What’s disappointing to me personally is that Thom Yorke once again thrusts his new love of glitch and future garage onto the band—he’d been running around with Flying Lotus, Burial, and Four Tet around this time—thereby removing the rock component that the band was capable of for the second time. Of course, this worked to their benefit on Kid A, but the band doesn’t feel as committed this time around. The songs just aren’t there. “Morning Mr. Magpie” and “Little by Little” are just “The Gloaming” and “Myxomatosis” respectively; “Codex” might as well be “Pyramid Song”; twitchy lead single “Lotus Flower” hits a wall as soon as Thom Yorke opens his mouth. “Feral” is fun, but it is no substitute for the excellent future garage coming out of the UK around this time.

Not only is the album not playing to Jonny Greenwood’s strengths as a guitarist or classically-endeared arranger that he was working towards, but also Thom Yorke’s strengths as a melodicist, lyricist or even vocalist. The only truly breathtaking vocal here comes early on “Bloom,” where his vocals slowly unfurl and we’re reminded of his incredible breath control at his vocal peak in 1995. And the sound design is incredible: what sounds like backwards drum loops and fragments of bass swelling up into a critical mass quite early, and the fact that Thom Yorke’s voice soars over this mix is great. The best is saved for last: over a tasteful rhythm section, Thom Yorke sings a melody in “Separator” that actually sounds genuinely happy. (Genuine question: is it their happiest song? Is it their only happy song?) As ridiculous an image as “I’m a fish now out of water / Fallen off a giant bird” might be, Yorke makes it seem like that feeling of falling—from a great height, so to speak—can also be freeing.

A Moon Shaped Pool returns to the dulcet guitar tones of In Rainbows with more aqueous piano and production. Gone are the twitchy electronic influences that made The King of Limbs halfway interesting. By 2016, I had already tapped out of my Radiohead fandom, and I found little here that I enjoyed to bring me back in. I liked the percussive attack on the strings of “Burn the Witch” because the string players used guitar picks, but I also think that the song sounds like it wandered in from a completely different album, which written 16 years ago during Kid A, it technically was. I liked the snatches of backwards vocals of “Daydreaming,” like a ghost harmonizing with Thom Yorke, and the impressionistic turn of the piano during the instrumental portions, but the song just restarts itself halfway through. I liked the ominous krautrock of “Ful Stop” but Thom Yorke hasn’t sounded menacing since “Climbing Up the Walls.”

The two best songs are at the very end. Greenwood had been making strides to be taken seriously as a composer outside of Radiohead, starting with the Penderecki-inspired Popcorn Superhet Receiver in 2005 which later found its way onto PTA’s There Will Be Blood which started their relationship together, and his string arrangement at the end of “Tinker Tailor Soldier” is frankly the only time since “Reckoner” that I’m impressed by his ability to compose within a Radiohead song. It would’ve been the best possible ending for the album if not for the re-make of “True Love Waits” that immediately follows, which might be my favourite Radiohead song of all time. That song first appeared on a Radiohead release in the live-only form on I Might Be Wrong played on acoustic guitar but is rendered here with achingly beautiful with electric guitar white-blue tones that bring the album title to mind. It reminds me very much of the guitar tones that Sufjan Stevens was using around this time, quiet and beautiful. You can swim in the song. The mere idea of “drowning” one’s own beliefs to start a family with someone else brings me to my knees.

Studio: Pablo Honey - C+ The Bends - B+ OK Computer - A+ Kid A - A- Amnesiac - A- Hail to the Thief - A- In Rainbows - A- The King of Limbs - B A Moon Shaped Pool - B Live: I Might Be Wrong: Live Recordings - B- Hail to the Thief (Live Recordings 2003-2009) - B

Fun read. I'm coming from the other direction though, listened to Mingus, talking heads, Brian Eno all thru the 80s and 90s... Still do, but can't listen too much. Love Monk too, but I really can't listen to him long now without my brain rebelling. Only started Radiohead with kid A, kinda like ok computer, never liked the first two albums... Anyway, I listen to Radiohead and the Smile all the time now.

First - I don’t think we can have too many deep dives in Radiohead. I think we all hear different things in their amazing complexity and it was cool to hear through your lens.

Agree with the B on Moon Shaped Pool but it’s a tough curve with some of their other classics. “Decks Dark” felt like the haunting simplicity of their early work.

Thanks for writing this - a perfect Sunday coffee read.