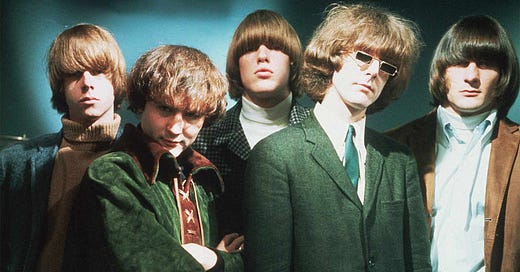

The reason why the Byrds were the Greatest American Band up until 1968—when they ceded that crown to Sly & the Family Stone, Aretha Franklin and the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, and of course, Miles Davis’ Second Great Quintet—is because they innovated relentlessly and were foundational to multiple genres in the six albums they released in the four-year span of 1965 and 1968. Six albums in four years: that’s a clip that they could only manage by releasing two albums a year on two separate occasions during that time.

On their debut album, they put folk music within pop/rock context—Billboard dubbed it folk rock—while casually inventing jangle pop almost two decades ahead of schedule. They released their psych rock classic in 1966, a year before the genre burst, and then promptly switched to country rock when the band met Gram Parsons and then moved to Nashville. In between these monumental achievements, they were one of the first rock groups to test out the Moog synthesizer because Roger McGuinn was fascinated with electronic instruments, and even though he couldn’t wield it properly—no one at the time could—it only demonstrated their experimented spirit. The Velvet Underground, another contender for the same title, didn’t change nearly as dynamically as did the Byrds in the same span of time, even though I’ll concede that they had the better studio album discography.

The Byrds’ cover of “Mr. Tambourine Man” was released 60 years ago today as their debut single, and it hit a milestone that the Beach Boys would not until the following year with “Good Vibrations”: the Byrds topped the charts on both sides of the Atlantic. The Beach Boys were, at this time, purely an American phenomenon, whereas the Byrds were instantly an international success for uniting folk and rock as well as being well-dressed heartthrobs.

Like the Beatles or the Who, I argue that the Byrds landed fully formed, and only evolved from there as they had (1) close and complex vocal harmonies thanks to David Crosby and Gene Clark behind the friendly voice of Roger McGuinn, (2) the incredibly muscular, rolling bass of Chris Hillman who came from a country background, and (3) Roger McGuinn’s arresting and unique sound from his twelve-string Rickenbacker: it was proto-jangle and proto-psych at once. Quoting Billy James from the liner notes of Mr. Tambourine Man, “The Byrds take [Bob Dylan’s] words and put them in the framework of the beat, and make imperative the meaning of those words. And there’s an unseen drive, a soaring motion to their sound that makes it compelling, almost hypnotic sometimes.” That soaring motion is purely from McGuinn.

What’s worth mentioning is that of all the Bob Dylan songs they chose to cover first, it wasn’t something ‘obvious’ from Another Side of Bob Dylan that would lend itself to being jangled or one that they could easily just put a rock beat under, but rather a then-unreleased song that they had to change the time signature in order to make it work which is bolder than the Turtles choosing “It Ain’t Me Baby.” Assuredly, the Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man” is not better than the Dylan original. Like so many Shakespeare film adaptations, the reason why it comes short is because they have to sacrifice too many words to transform it into this new context, but because of those three elements mentioned above, it’s worthy in its own way: those opening measures are the dawn of spring, and no better time to release it then mid-April when the snow is hopefully gone for good.

The album is mostly made up of covers, including three more from Dylan, none as special: “All I Really Want to Do” loses its humour; “Spanish Harlem Incident” loses its sexuality. “Chimes of Freedom” is the best of them, but that’s because of the fluid guitar lines and muscular bass-line. Byrds original “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better” gets silver to “Mr. Tambourine Man”’s gold: those chords are pure power pop, but scuzz them up and you’d have garage rock as the Leaves did with “Hey Joe,” strip them of their harmonies and you get twee, as the Magnetic Fields did on “Deep Sea Diving Suit.” The album’s faultier second half is elevated by covers of Jackie DeShannon’s “Don’t Doubt Yourself, Babe” and Vera Lynn’s “We’ll Meet Again”: the former works well with a rock beat, and Lynn’s touching WW2 songs is given a sardonic reading by the Byrds appropriate for the Vietnam War.

Just one week after the release of their debut, the Byrds hit the studio again to record Turn! Turn! Turn! which they released at the end of the same year. Personally, I don’t think there was any harm if they sat on it for a few more months: the Byrds’ harmonies and jangle guitar tone are both very summery sounds for me, so it doesn’t make sense to release a Byrds album in December except to capitalize on the Christmas season. The vocal harmonies on “Turn! Turn! Turn!” and Dylan cover “Lay Down Your Weary Tune” are polished and sound closer to gospel than anything from their debut, and I’m not just saying that because the title track pulls from the Book of Ecclesiastes: Gene Clark’s vocals are fuller than ever. McGuinn’s originals “It Won’t Be Wrong” and “Wait and See” are not as good as “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better,” although the latter has the noteworthy lines “I think I’m gonna love her / And if it lasts forever I don’t care” whereas a lesser songwriter might have fallen for the more banal “And if it doesn’t last forever, I don’t care.” And while I commend them as brave for picking a lyrical song like “Mr. Tambourine Man” to cover, I reprimand them for trying to do “The Times They Are A-Changin’”: “The Times” is a song that’s just bound to fail no matter who’s doing it, possibly because doing so suggest that the times haven’t changed. I’d recommend looking for the expanded version to get your hands on “(It’s All Over Now) Baby Blue” (not as good as the original either, but they capture the fervor) and “She Don’t Care About Time,” which quotes “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,” appropriate for growing baroque pop of the mid-60s (“There are places I remember, all my life…”).

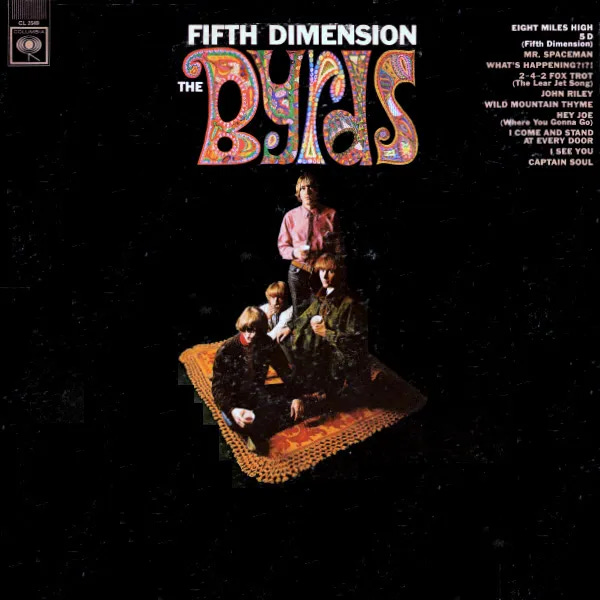

I’ve come to cherish Fifth Dimension’s open-armed embrace (“And I opened my heart to the whole universe and I found it was loving”), which they even extend to aliens (“Hey, Mr. Spaceman / Won’t you please take me along?”) far more than much of the darker, sexier, and more insular psychedelic rock to come—i.e. I rank this ahead of the debuts of Pink Floyd and the Doors—and what cinches the deal is that there’s also a wider embrace of sounds. This band, once so indebted to Bob Dylan while looking like the Beatles, adds John Coltrane’s sheets of sound into the mix while working with Van Dyke Parks. Meanwhile, “Hey Mr. Spaceman” is a quasi-country bop that forecasts their leap to country.

It might have been their best album if not for so many misfires. You can scotch “I See You” (a blatant re-write of “Eight Miles High,” which feels draggy despite being significantly shorter), “Captain Soul” (a decent instrumental) and “2-4-2 Fox Trot” (a potentially interesting sonic experiment that they didn’t write a song for). And “I Come and Stand at Every Door”—inspired from a haiku by Nazim Hikmet about children who died in the Holocaust—could’ve been shorter or benefitted from something to bring out that skeletal arrangement. And while the Leaves might’ve gotten credit for submitting the first recording of “Hey Joe” which would become a garage rock standard, it was the Byrds who inspired them when the Leaves saw them performing it live. The Byrds’ recording isn’t great—they’d all be invalidated by Jimi Hendrix’s debut single that same year anyway—but that first minute = barreling down to the gun store.

So yeah, as you can see, there’s a lot of problems — that’s already half the album! But the rest is truly something special: the swirl of the guitar and tumble of the rhythm on “5D (Fifth Dimension)” and the “Oh!” at 1:16, like discovering there’s a whole universe ready to love you; the hymnal singing of “Wild Mountain Thyme”; the cuteness of “Mr. Spaceman?” that rhymes “I was feeling quite weird” with “My toothpaste was smeared.” There’s a genuine loneliness in “What’s Happening?!?!”, the first time David Crosby sang on a Byrds track, a feeling emphasized by the fact that the guitar parts don’t ‘activate’ during his lines. And of course, “Eight Miles High,” is the best song here, potentially their crowning jewel. This would be their last single to break the top 20 chart in America (peaking at #14), as well as hitting a more-than-respectable #24 on the British chart. McGuinn’s guitar is being manipulated into sounding like a cross between a sitar and a saxophone as it shoots and splatters out notes in the style of John Coltrane. And while McGuinn gets (deservedly) a lot of the praise here, the success of “Eight Miles High” is a result of the whole band: the opening measures are all Chris Hillman. Meanwhile, Michael Clarke, who joined the band because of his haircut and not his drumming resume, finally works up something that isn’t totally embarrassing (he was easily the band’s weakest member).

Younger Than Yesterday is frustrating. Songs like “Have You Seen Her Face” feel like a stepping stone towards Fifth Dimension by mixing psychedelic rock with their original folk rock, but it was released afterwards. Elsewhere, they retreat back to Dylan covers, which, makes sense when you consider that the now-revered Fifth Dimension was their worst-charting album, so they play it safer here, but when Gene Clark left the band—from an ironic fear of flying—he took the band’s harmonies with him, and the album is hopelessly frontloaded. No one needs the second side. “Thoughts and Words” is disjointed, with no thought to transition from the verses and the choruses. The Bob Dylan cover, “My Back Pages” is a safe reading compared to their others, and feels like they’re just reciting the words. David Crosby sings lead on “Mind Garden” and it’s overwrought, and would be the worst song on the album if not for “C.T.A. - 102” where they dick around with sound effects. To broadcast the dearth of songwriting, they re-do “Why” that first appeared as a b-side to “Eight Miles High.”

Thank goodness the first side has three great songs. Opener “So You Want To Be a Rock ‘N’ Roll Star” has the album’s most direct guitar line and melody, rounded out by horns, and later covered by Patti Smith just as she was running bone-dry out of ideas. Before this point, covering Dylan over and over hadn’t improved their lyrics, but “Star” functions as a fantastic critique against the music industry placing importance on image ahead of music (“When your hair’s combed right and your pants fit tight / It's gonna be all right”). “Have You Seen Her Face”’s face-melting guitar solo is reminiscent of “Eight Miles High” although in a far more traditional pop/rock song about love where you wouldn’t expect one. And “Renaissance Fair” is one of their best songs: over Hillman’s Indian-inspired bass-line, the melodies have a surreal quality to them such that the words feel far more ambiguous than they let on.

The Notorious Byrd Brothers peaks early by bursting forth with “Artificial Energy,” a song whose vocal effects were inspired by “Tomorrow Never Knows,” and then immediately quiets down, and from there, the album ebbs and flows like a weird dream: sweet, sweet vocal harmonizing lulling you to sleep on “Draft Morning” that are interrupted by military horns to make it feel like you’re being conscripted into the army; “Old John Robertson” bouncing towards its strange release of “Then she sighed, then she died” before the chamber instruments come in, do their dance and leave, their swirling colours lingering in the air for the rest of the song (wish Gary Usher cooled it with the effects there). “Change is Now” may be the peak of their careers where Michael Clarke’s drums chew up the scenery and spits it back out such that the title does become a mantra over the beat’s march. And to boot, the song has elements of country and psychedelia in the guitar solo that makes you’re floating over the land. It’s the golden mean of everything the Byrds stood for in less than 3 and a half minutes.

The songs after “Old John Robertson” feel slighter: “Tribal Gathering”’s wordiness obscures the verses and the Jefferson Airplane midsection feels like it wandered in; “Space Odyssey” is a psychy dirge that’s the worst song on the album. Crosby was becoming bored with the band, upset that they continued to cover others, including the lovely “Wasn’t Born to Follow,” and that they refused to include his song about threesomes was the final straw (the Byrds and ABBA were two great bands let down because some of the men desperately wanted to sing about having two girls at the same time): he was let go before the album’s release. He gave “Triad” to Jefferson Airplane, and he might’ve taken “Draft Morning” with him too, but the band recorded it without him and wrote new words to it. Michael Clarke also left, dissatisfied, and the band had to get Hal Blaine—He of “Be My Baby” and the Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man”—to finish the record.

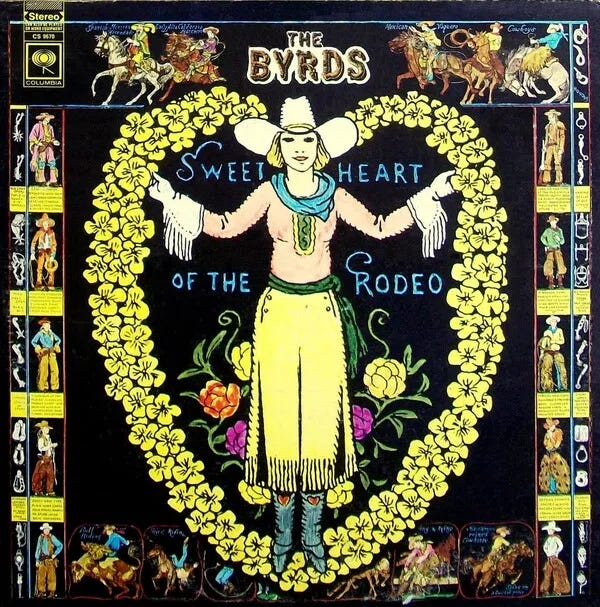

Though The Notorious Byrd Brothers is secretly their best album, it charted worse than their previous albums: they were no longer folk rock heartthrobs, nor in vogue with psychedelic rock. Reduced to a duo, McGuinn and Hillman brought Gram Parsons in, who convinced both to take the plunge into country rock. I like Sweetheart of the Rodeo when it’s on, but I never remember a thing besides the Bob Dylan covers that bookend the records afterwards: contextualizing folk music with a rock beat in 1965 was revolutionary, and doing the same with country three years later just didn’t have the same effect. (Non-country critics may disagree there: the album would continually appear on the Rolling Stone lists.) I love Dylan’s “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” that he cut with the Band on The Basement Tapes, but the Byrds’ version is better: the country guitar lines are clean and melodic, and if that weren’t enough, Hillman carves out even more melodic territory with his bassline.

They haven’t yet settled into complacency on Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde, and apparently the cover—of the cowboys riding their own faces—is meant to represent the different versions of the Byrds. The results are a mess: “This Wheel’s on Fire” simultaneously blusters and bores; “Bad Night at the Whiskey” is anemic; the singing on “Candy” nudges at the ribs constantly. One positive is that Clarke’s replacement Gene Parsons is a tighter drummer, and his drumrolls feel out of Clarke’s reach. They revisit “My Back Pages” which points to how they’ve exhausted their good ideas, proved again the following year when they would remake another Dylan song they already recorded. A non-album single of “Lay Lady Lay” was released a few months later with producer Bob Johnston who overdubbed the shit out of it without the band’s consent so they never worked with him again; on the expanded version of the album, you can find the ‘naked’ version which is similar to “The Long and Winding Road” where the song just wasn’t good enough regardless.

The title track of Ballad of Easy Rider, “Flow, river flow…”, over a finger-picked acoustic guitar that actually does bring to mind the image of moving, calm water, means this is, by default, a better album than Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde, but I think it stands for something far more sinister: this is where they start influencing the Eagles. Chris Hillman is sorely missed on “There Must Be Someone (I Can Turn To),” who left the band because of disagreements with the band manager Larry Spector, forming the Flying Burrito Brothers with Gram Parsons whose drummer would be ex-Byrds Michael Clarke. A few bones are tossed to Byrds fans that made it this far, both of them playing like slaps in our faces: the obligatory Dylan cover in “(It's Alright Now) Baby Blue” in the style of the Eagles, and closer “Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins” is the charming filler of the previous albums that isn’t remotely earned. Gram Parsons’ influence on the band was ultimately a detriment because he was so focused on making country music hip again that Roger McGuinn’s curiosity into other genres took a backseat to the Byrds’ newest member: for example, he shelved a concept album he was working on about the history of American music—from folk to country to jazz to rock to psych to electronic—and this band of former trailblazers settled for their last albums from here on out.

(Untitled) is one of those half-live/half-studio albums that felt like the label’s way of making an extra buck because no one was going to be satisfied with either the live or studio discs on their own here, but packaged together, ‘hey, if the country stuff is too anemic, here’s some energetic live jams!’ and ‘hey, if the live versions don’t do their originals justice, then there’s some original material!’ The original material is anemic, even when Roger McGuinn busts out the Moog again on “Just a Season” or when they try to get groovy on “Hungry Planet” which is so heartbreaking considering how full and majestic the Byrds were when they first took flight. For the live set, “Eight Miles High” gets stretched into a 16-minute jam to fill out an entire side and commits the cardinal sin of being boring while doing so.

The Byrds don’t think of Byrdmaniax fondly, and place the blame squarely on producer Terry Melcher who added gospel choirs and chamber instruments and overdubs just like Johnston did on “Lay Lady Lay.” One genuinely good song that almost rivals “Ballad of Easy Rider” as their post-1968 best song comes early in opener “Glory, Glory” which makes me think of Big Star’s #1 Record soon-to-come; the vocals even sound like Chris Bell, and it has the same holy feeling that Bell was able to inject into Big Star. But many of the songs fall flat on their face: the inexplicably long “Tunnel of Love” has a John Lennon impression that leaves you wondering why you’re not just listening to the source directly; the horns on ‘I Wanna Grow Up To Be a Politician” are ridiculous, with atrocious harmonizing, ironic or not. By the time you’ve reached the bluegrass instrumental that feels like the unearned throwaway instrumental closer, it’s already been too long and you quickly realize there’s still more to come.

The band quickly put together Farther Along and released it 5 months later as an apology. It ended up performing worse. (Maybe the problem with Byrdmaniax wasn’t the producer after all!) Most of the songs are fine in that early-70s country rock sorta way when the stakes are too low for anyone to care a la ‘at least the bar band is playing on beat!’ “Get Down Your Line” has a nice country bump, but one misses what Chris Hillman would have done if he were still around. “B.B. Class Road” would be their worst song except that title’s been claimed a dozen times over by this point. “Tiffany Queen” deploys The Almighty Riff but doesn’t have the courtesy to make it sound good. One imagines what Paul Simon would’ve done with a song titled “America's Great National Pastime” although the Byrds’ rhymes are fun: “One of America’s great national pastimes is chocolate fudge / Carryin’ a grudge, bribin’ a judge / One of America’s great national pastimes is poisoning rain / Acting insane, inflicting pain.”

In 1972, McGuinn fired Gene Parsons—no relation to Gram—who had replaced Michael Clarke. In 1973, Clarence White, whose B-Bender let him bend the b-string to sound like a pedal steel guitar, was killed by a drunk driver. Starting at scratch again and incentivized by David Geffen paying everybody for a reunion, McGuinn brought in the original Byrd members for Byrds, an album so bad that they called it quits for good.

Mr. Tambourine Man - A Turn! Turn! Turn! - A- 5th Dimension - A Younger Than Yesterday - B+ The Notorious Byrd Brothers - A Sweetheart of the Rodeo - B Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde - C+ Ballad of Easy Rider - B- (Untitled) - C Byrdmaniax - C Farther Along - C Byrds - C

Great reads says this diehard Byrds fan who agrees with much of your scathing honesty. 👏👏👏👏

I never seriously understood either yours or Nathan's arguments against Younger Than Yesterday. The grounds by which both of you attack the album seem perfectly applicable to the Byrds in general: if you find "Thoughts and Words" disjointed (how can you make this argument when you give Fifth Dimension an A, having songs even more disjointed) or songs like "Time Between" or "The Girl With No Name" to be filler, I could say that about a very sizable chunk of their discography, most notable Turn Turn Turn and Notorious. If you find "My Back Pages" to be recitations, then I do not see seriously see such a big gap between this and the others Byrds covers of Dylan songs: the instrumentation is as pretty as usual and it was a theme that fit with the Byrds catalog (like "Goin' Back").

The truth is (or at least how I see it) is that the band always had a bit of a songwriting problem in shaping their sound into songs that do not collapse into (beautiful) mush, and their praised Dylan covers honestly were fairly humorless, passively internalized, and had a very stiff interpretation of his style not unlike the other stiff folkies of the revival. On those grounds, I think it is *very* hard to make an argument that this is weaker than the other albums, and it also to me makes it very hard to believe either of your points about the Byrds being the single greatest American band (though, in agreement about VU, Muscle Shoals, and Family Stone being the great American bands of the era): even if you don't like style of the Doors, for example, the aesthetic they crafted was more natural, versatile, and visceral than the Byrds, which is why they survived the mid 60s and the Byrds did not.