Top 100 Albums of the 1980s (100-81)

50 bucks and that's all you've got? Yeah, I love you, I love you a lot

I first attempted this list more than five years ago, and for my 50th post here, I thought I’d resurrect it to celebrate. Most of the words have been greatly edited, but more than 20% of these picks are new — either discovered or grew on me over the last 5 years.

#100. The D.O.C. - No One Can Do It Better (1989)

As early as 1989, Tracy Lynn Curry, better known as The D.O.C., showed the limitations of categorizing hip-hop by region between ‘east coast,’ ‘west coast’ and ‘the south.’ Sonically, his debut album is a west coast hip-hop album for sure. After contributing to N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton, Dr. Dre produced the D.O.C.’s debut album in full, and a lot of the beats have a similar sound. But in spirit? This is a southern rap album through and through. For starters, Curry ain’t even from Compton originally; he’s a Texan, which informs his rapping, “The boss, straight from The South,” he declares on “Lend Me An Ear.” Later on, Andre 3000 considered the D.O.C. as “the first real rapper that we [Southern rappers] looked up to that could really rap.” Thus, No One Can Do It Better positions the D.O.C. as—at once—the west coast and south’s answer to east coast wordsmiths and flow-masters Rakim and Big Daddy Kane.

Released in 1989 between Straight Outta Compton and The Chronic, consider No One Can Do It Better as the stopgap between the two Dre albums. It’s funkier than Straight Outta Compton but not as funky as The Chronic and it’s grittier than The Chronic but not as gritty as Straight Outta Compton. To wit, that indelible bass-line on “Let the Bass Go” is sped up a tad from Isaac Hayes’ “No Name Bar” from the Shaft soundtrack, and Dr. Dre replaces that song’s drums with a much heavier one so it can meet the album’s funk and grit quota at the same time. The highlights are evenly paced throughout from the more than funky enough, more than hooky enough opener, to “Beautiful But Deadly” taking the fluid guitar from Funkadelic’s “Cosmic Slop” and turning it into straight-up rap rock (ignore the lyrics which manages to be misogynistic and homophobic at once), to the cool, exotic little wind instrument in the hook of “The Formula” which contains some of the D.O.C.’s best rapping on the record (“Originality is a must whenever I bust / A funky composition, it's crushed and I trust that you know it”). “Lend Me An Ear,” sounds modelled after “Straight Outta Compton” with Dr. Dre filling out the verses with a string sample sounding like an alarm blare, and in lieu of a chorus, he drops a break full of cheerleader vocals (“Go! Go!”) and horns that link to the next verse.

We all know what happened next: five months after the album’s release, the D.O.C. fell asleep at the wheel and got into a terrible car accident that damaged his vocal cords, preventing him from rapping, delegated instead to doing Dre’s ghostwriting.

#99. Sun Ra - A Fireside Chat With Lucifer (1983)

The problem with Sun Ra is that he put out a bunch of bullshit, and no one has the time to wade through it all. But A Fireside Chat With Lucifer is a post-Lanquidity highlight, and what’s attractive about it is that you get to see different sides of the alien jazz-man.

Released as a single in 1982, “Nuclear War” is genuinely funny—“If they push that button / your ass got to go / what you gonna do (what you gonna do) / without your ass (without your ass)”—and I find it fitting that it’s on an album with this title because the back and forth of the vocals really does sound like a fireside chat. (For people looking for more of Sun Ra’s humour, I recommend backtracking almost a decade earlier to 1974’s single “I’m Gonna Unmask the Batman.”) While it’s clear that Sun Ra was not exactly apolitical for an alien, he was so often in space that “Nuclear War” seems to have come out of nowhere. “Retrospect” brings me back to 1978’s Lanquidity, Sun Ra’s belated and brief foray into languid jazz fusion. There's a sadness permeating throughout, especially from the funereal horns—appropriate for a song post-nuclear fall-out—which would be too normal for Sun Ra so he starts adding zips and zaps before fully committing to the electric organ.

“Makeup” is the shortest song here, and it’s also the happiest cut. Samurai Celestial (perhaps the coolest name in jazz)’s drumming comes close to swing, while Sun Ra’s organ tones are sunny, bathing the saxophone solo in rays of warmth. That’s the first side, and the second side—just the title track spanning twenty minutes—reminds you that you’re listening to Sun Ra as the band launches into space and eventually finding their way onto a distant planet.

#98. Kool G Rap & DJ Polo - Road to the Riches (1989)

Had Kool G Rap been able to follow up his debut single “It’s a Demo”—from 1986, the first record released by Cold Chillin’ Records—sooner, then doubtlessly he’d be more widely considered as one of the pioneering voices in rap music: imagine the internal rhymes, multisyllabic attack and alliteration of Rakim, but telling tales of street violence instead.

I will say that unlike Rakim, Kool G Rap isn’t nearly as versatile: he isn’t able to switch flows on a dime, and his penchant for deploying three rhymes within two lines grows wearying over the course of an album. While I’m on the flaws, the Gary Numan sample of “Cars” was a possibly interesting choice but the sample goes nowhere, and Kool G Rap’s verses are underwhelming anyway, with a lot of reverb and echo applied to the last words—“But yo one day you will see me in a fly Lamborghini / On my way to the beach picking up girls in bikinis”—that makes it feel like they’re nudging you in the rubs to make sure you pick up on the ‘oh so impressive’ rhymes. And I’m still trying to figure out who actually rapped about sex in a way that didn’t leave me feeling icky or question if the rapper ever had sex to begin with: “She kissed me low and then proceeded up / Bedsheets heated up, the pace is speeded up / Slowly but surely we reach our destiny” from “She Loves Me, She Loves Me Not” is the stuff of horrifying fanfiction.

But when Kool G Rap and DJ Polo (/Marley Marl)—there’s some dispute of how much Marley Marl and how much DJ Polo did, with DJ Polo allegedly all the samples were his ideas, but needed Marley Marl to work the tech—start flowing, Road to the Riches feels unstoppable. “The innovator with greater data, deeper than a crater / Of course, Polo’s the boss of the crossfader” and “I run rappers like races, cut them like razors / Burn them like lasers, and stun them like phasers / Cause my brain thinks and it blanks your memory banks” are simply awesome (both contain 3 rhymes in 2 lines that I mentioned earlier), while DJ Polo hooks Kool G Rap with Incredible Bongo Band’s “Apache” on “Men at Work” (missed opportunity not to sample the opening drums of “Down Under!” by the Australian band with the same name), the guitar squeal of “Poison” and the snaking bass-line of “Butcher Shop.” Even the romance cut has a cute keyboard figure that’s practically whistled. The closest any rapper got in the 1980s to sounding like 1994 within the decade.

#97. The Go-Betweens - Liberty Belle and the Black Diamond Express (1986)

Two of my hot takes on this list is right here, which is that (1) this is the best indie album of the antipodes, and (2) this is nerdy jangle pop that edges out the Smiths for me, a band whose melodrama I simply outgrew. It’s true that “Streets of Your Town” from the far-more acclaimed 16 Lovers Lane smokes every song here out the water, but that album felt like the Go-Betweens’ bid to go big—and indeed, they scored their first top 100 hit overseas—such that the hooks feel like they’re made by a completely different band than the book-smart, gun-shy one that I fell in love with here.

Don’t believe me that this is their best? Take it from drummer Lindy Morrison then, who says this is her favourite album of theirs. There’s no filler, nary an awkward hook or wayward line, and there’s more colour here that seems to have evaporated a little for 16 Lovers Lane, including country bass-lines, strings, accordion, vibraphones, loops; Robert Forster said that, “Our intention was to expand on the crisp, woody sound of Before Hollywood, to include a grander, more exotic range of instrumentation.” The production (self-produced and assisted by Richard Preston) is a little flat, but that extra instrumentation shines through, turning a potentially gray world into a far warmer one, especially with the accordion on “The Ghost and the Black Hat” and the vibes on “Twin Layers of Lightning”; closer “Apology Accepted” would have been too white indie sad-boy but the piano elevates it into a beautiful highlight.

In classic Beggars Banquet fashion, the best songs are the side openers. “Spring Rain” is pure jangle pop while “In the Core of the Flame” traces the lineage of the genre back to post-punk, the rare Go-Betweens song to just rock out convincingly. The former gets my vote for their second-best song after the obvious one (“Streets of Your Town”) which pairs up jangly guitar against a country bass-line so it’s almost as if we’re hearing two different eras of the Byrds at once, something that the Byrds never bothered with.

#96. The Rolling Stones - Tattoo You (1981)

There are cooler, hipper albums than this one that deserve praise but I simply cannot imagine making a list of 100 from this decade without making room for this album. Once heralded as the Stones’ last-great album, Tattoo You’s reputation seems to have declined, and now that accolade is more readily given to Some Girls. Bring this one’s reputation back up. What’s incredible about Tattoo You is how the entire album is assembled from whatever the band could find in the vaults. The songs on this album date back all the way to late 1972 all the way through to 1980, but not that you would know because almost every song is a winner! Crown it the best b-sides compilation!

“Start Me Up” is, of course, the big hit, and like a few other Rolling Stones song, peaks way too early. I love that the opening measures do sound like a genuine ‘starting up.’ It’s a great song, a keyed-up rocker as much as Some Girls opener “Miss You” was a keyed-up groover, and yet, it’s nowhere near the best song on the album. Written originally in 1975 for Black and Blue, “Start Me Up” feels like a conscious retread of “Brown Sugar,” and it’s nowhere near as good by comparison. For starters, “Heaven” and “Waiting on a Friend” are both better. The former is so effortlessly psychedelic thanks to the shimmer of the production—though they purged the excess on Their Satanic Majesties Request, they never totally dropped the psychedelia—while closer “Waiting on a Friend” is as good an emotional number as they could have pulled off at this time, thanks in no small part to old pal Nicky Hopkins’ piano chords but especially to Sonny Rollins’ solo, taking this song to places that the Stones wouldn’t have been able to reach without. The saxophone colossus appears two other times on this album, including elevating “Slave” with a solo that flashes his old brilliance in a way that he barely did in his own discography this decade.

Elsewhere, “Hang Fire” beats out all the other new wavers of ‘81; it’s just so darn spunky, smoothed out by the addicting ‘doo-doo’s that bookend the short song. “Little T&A” reminds me of the lighthearted, low-stakes and knocked-out-the-park casual masterpieces of their masterpieces some 12 years ago; letting Keith Richards take lead was wise since he barely enunciates the words, and why should we care about the words in a song with this title anyway. Just a little rockabilly-influenced song that I would genuinely miss if I never heard again. Not just their last great album, but possibly also their last end-to-end listenable album.

#95. Geinoh Yamashirogumi - Symphonic Suite AKIRA (1988)

Geinoh Yamashirogumi is a Japanese music collective led by Dr. Shoji Yamashiro, with the release of 1986’s Ecophony Rinne—their first album to combine synthetic sounds with natural ones—they got the attention of Katsuhiro Otomo, who immediately commissioned Geinoh Yamashirogumi to soundtrack the Akira anime. This was well before any frames were completed such that the visuals were created to fit the sonics, as opposed to the traditional vice versa, so miss me with that “works better in the context of the film” critiques.

The opening sounds that you hear is a thunderclap followed by rain, and then helicopters circling overheadm appropriate given the film’s theme of government oversight. And then we’re treated to the sounds of the Balinese Jegog: a percussion instrument fashioned out of bamboo that leads to the “jungle”-esque feeling of the post-minimalistic “Kaneda” theme. Despite the name, “Kaneda” doesn’t just introduce the anime’s main protagonist, it also introduces all of the characters as the choir sings “Kaneda / Tetsuo / Kai / Yamagata” after “Nakama hashiru” (translation: friends running) at the end, introducing the soundtrack’s sonic motifs of polyrhythm and choral voices. Hence the title: “Symphonic Suite,” it’s called after all, and Dr. Yamashiro has noted the influence of Bach’s Mass in B Minor which is pretty evident in the dramatic, booming vocals throughout.

True, some of the musical cues are given extra meaning with the context of the film: the back-and-forth between the grunt-y breaths and the Balinese Jegog bamboo percussion of “Battle Against Clown” is a sonic representation of the rival motorcycle gang (named ‘clowns’) fighting against Kaneda and his friends. But these strange textures work fine on their own as well; their industrialism and modernity sonically representing the film’s exploration of the destruction of Tokyo and its rebirth as Neo-Tokyo, and Neo-Tokyo’s own subsequent destruction.

#94. Jungle Brothers - Done by the Forces of Nature (1989)

You never hear about these guys anymore unless it’s out of obligation for their work as the first hip-hop act to collaborate with a house musician or as part of the Native Tongues collective that helped usher in the conscious and jazz rap of 1990s. But this album is such a fun record that it deserves more than mere respect. Despite the fact that this runs 16 songs long, you’ll remember many of them fondly, which simply cannot be said of more renown rap classics that appear earlier on this a=list.

Admittedly, Mike Gee and Afrika are not great rappers, and the rhymes, mostly monosyllabic, are basic to the point that when either lands a good one, you’re almost shocked as with the corners-order-older-colder-bolder-takeover rhymes on “Beyond This World.” De La Soul joins on “Doin’ Our Own Dang,” returning the favor for the Jungle Brothers appearing on De La’s own posse cut “Buddy” earlier that year, and Posdnuos and Dove are so much more distinct that you wish they were the ones rapping over these beats, or else featured more. That said, Afrika’s second verse on “Acknowledge Your Own History”—where the group’s focus on Afrocentralism which distinguished them from De La Soul—shines bright, “I looked into the table of contents / They wrote a little thing about us in the projects / Only history we make is if we kill somebody / Rape somebody, but other than that we’re nobody.”

But the beats provide such rhythmic energy and textural colour that you never mind the rapping, such as the surprise of hearing Jimi Hendrix over these mellow bass-lines 3 minutes into the song, or the deployment of sleighbells to thicken the Black Sabbath drum beat on “Beeds on a String.” “Black Woman” has that an almost hazy feeling to it with the floating female vocals. “In Dayz 2 Come” uses a Blondie sample to help colour the sample of “The name of the game is rapture!” while the first section with that flute is as close as the album gets to jazzy despite the oft-mis-tagged “jazz rap” label. “Belly Dancin’ Dina” is a skip because the sex talk is predictably clumsy—“I wanted to take her home with me / Behind the bush and up my tree” gives me night tremors—while the way the samples drop out of “Feelin’ Alright” only highlight how weak these guys can be on the microphone.

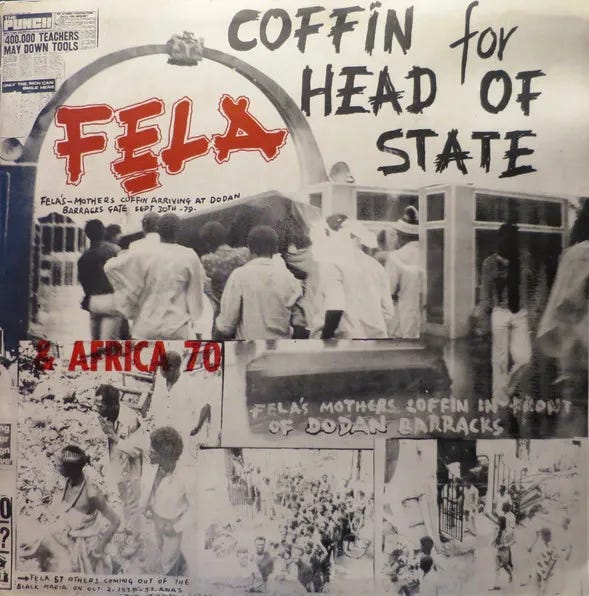

#93. Fela Kuti - Coffin for Head of State (1981)

This is Fela Kuti’s best album of the decade because it’s his most politically seething—Beast of No Nation, despite the cover depicting Thatcher, Reagan, Botha, and Seko all with demon horns and blood on their fangs, doesn’t come close—which juxtaposes with the groove, sporting an infectious, sunny keyboard melody that makes me think of late-60s garage/psych rock.

Ultimately, I regard Kuti in the same manner as I do Bob Marley: masters of a very distinct sound whose big contribution was making a very lively music political, or maybe the other way around: they made intensely political music extremely lively. Kuti’s political music, such as on Zombie where he equated the military to zombies, got the attention of the Nigerian government, who sent a thousand soldiers to Fela’s house, beating and incarcerating the bandleader and tossing his 78-year old mother out of the second-story window; she would succumb to her injuries a year later.

Coffin for Head of State is Kuti’s response, with the cover depicting Fela Kuti and his bandmates delivering the coffin of his mother to the military’s doorsteps (which of course, resulted in all of them being beaten when they refused to remove it). I get why this album, with only one groove instead of two, or Zombie’s three, and the general lack of Tony Allen which hurts all of Kuti’s post-70s albums, typically doesn’t rank in Kuti’s top five, but it easily does for me. Both the rattling off of the word bad (“And them do bad-bad-bad-bad things”) and the falsetto at the 16:16 mark are some of the most striking moments in his career to me. At 23 minutes, it’s the shortest album to appear on this list.

#92. Mission of Burma - Vs. (1982)

Mission of Burma’s first iteration was short-lived—they only released one album and one EP before disbanding after guitarist Roger Miller developed tinnitus as a result of their loud live shows—but that they are mentioned consistently in the post-punk history books (Michael Azerrad’s Our Band Could Be Your Life and Simon Reynolds’ Rip It Up and Start Again) proves just how special their work was. One bemoans the lack of anthems on their debut album compared to Signal, Calls, and Marches EP (at least, that’s how Robert Xgau feels: “Is it merely the cornball in me who wishes these stiff, snarling, abrasive rave-ups would break into anthem a little more often?”), but the album feels far more accomplished.

Opening “Secrets” demonstrates outright just separated this band from other post-punkers, which is not-so-secret weapon Martin Swope, inspired by avant-garde classical composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage, who adds in tape manipulation and additional percussion. Remove him, and “Secrets” would be a bad-ass one-chord post-punk groove, but he helps bring the song to climax with his touches with the tape loops around the 0:55 mark after that incredible bass-line. It isn’t until 2 minutes when the vocals come in, and yet, this band manages to captivate my attention all the way through in a way that say, Wire (who they often get compared to), might not have been.

The album also proves how broad a term like “post-punk” is: within this album, you get a classic punk song in “The Ballad of Johnny Burma” (“I say my mother’s dead, but I don’t care about it! I say my father’s dead, but I don’t care about it!”, which made me really feel for the guy until I read from Azerrad that his parents were doing fine at the time), a Glenn Branca imitation in “New Nails,” and even pseudo-thrash metal in “Fun World” with the guitar barreling down over drummer Peter Prescott’s skitter.

#91. Andrew Hill - Shades (1987)

Is Andrew Hill underrated? It’s a question I seriously dwell on: his Blue Note records released between 1964 and 1970 are rightfully regarded as highlights of avant-garde jazz, and yet, any discussion about Hill will always seem to frame him as silver to Thelonious Monk’s gold, and by the same token, no one seems to care about Herbie Nichols’ bronze. But Blue Note co-founder Alfred Lion considers Andrew Hill his last major discovery, and in the overcrowded avant-garde jazz of the 1960s, Hill carved out his own space. Despite similarly angular improvisations and strange compositions, you wouldn’t confuse him with Monk. If Hill isn’t underrated, then I posit a modification: his post-Blue Note records must be as I never hear anything about them. Not a single whiff of praise. Despite slowing down in output, he kept making great albums all the way until his death in 2007. Shades is Exhibit A even though its greatness sneaks up on you: it’s a far more “normal” record compared to what he was making under Blue Note, and he even leans into the Thelonious Monk comparisons by teaming up with Monk drummer Ben Riley, and opening the record with a Monk tribute.

The album contains two trio cuts, “Tripping” and “Ball Square,” backed by bassist Rufus Reid, and four songs as a quartet with saxophonist Clifford Jordan to provide a foil, something that Hill hadn’t bothered with on a studio record since 1975, preferring the piano trio or solo piano formats instead. On “Monk’s Glimpses,” Hill’s improvises in his classic way, playing short lines that seem to operate on their own rhythmic logic while the rhythm section holds the line. And then Jordan takes over, articulating the melody far clearer in contrast to Hill who was more abstract. Of these six new compositions, all by Hill—he preferred honing his own songs, which is probably why he didn’t work as a sideman for others—only “Domani” is reminiscent of that old (black) fire. Part of the problem is that Rufus Reid doesn’t come up with anything labyrinthian for Hill to navigate, forcing Ben Riley to soldier that task by himself.

“Ball Square”—which he would revisit on the far more ambitious and far more difficult Dusk in 2002—ranks high in my favourite Hill compositions thanks to its strange theme: Hill drops a few seemingly disconnected piano lines and establishes a ton of empty space for Riley to figure out that eventually leads into a melody, clear and beautiful, that soars over Reid’s bowed bass notes. It’s proof that even when Hill was being direct, he was always delightfully playful.

#90. Run-D.M.C. - Raising Hell (1986)

This is the earliest hip-hop album that appears on this list (although I did consider LL Cool J’s Radio), and I don’t think it’s a coincidence since you can very easily argue that this is the exact moment where the ‘golden era’ of hip-hop began. Run-D.M.C.—Joseph ‘Run’ Simmons, Darryl ‘DMC’ McDonalds and Jason Mizell aka Jam Master Jay—were already the first hip-hop group to release an album that went gold with their debut album in 1984, and then the first hip-hop group to release an album that went platinum with their sophomore in 1985, so the only barrier left was multiplatinum, and that’s exactly what they did with Raising Hell especially thanks to rap-rock crossover and mega-hit “Walk This Way.” Personally, I think Rick Rubin pushing “Walk This Way” onto Run D.M.C.—who had never heard the song in full, only the drum loop, and who was firmly against it being released as a single—was a greater contribution to popular music than pushing “Hurt” onto Johnny Cash (who was similarly reluctant), and between Run-DMC, Beastie Boys’ debut and Slayer, 1986 was Rick Rubin’s year and no one else’s. (“Walk This Way” also brought Aerosmith back into the limelight after years of flailing around; they immediately followed up with comeback album Permanent Vacation and re-entered popular consciousness.) Most wisely of all is that they remake it instead of doing the obvious thing of sampling it for any rock naysayers against rap music.

The album is more front-loaded than any U2 album. “Peter Piper” has the rappers alternating lines and even words with one another (“Jack B. (NIMBLE!) was (NIMBLE!) and he was (QUICK!) / But Jam (MASTER!) CUT FASTER, JACK’S ON JAY’S DICK!”) or the inventive rhymes (“‘Cause he’s adult entertainer, child educator / Jam Master Jay king of the crossfader”; “He’s the better of the best, best believe he’s the baddest / Perfect timing, when I’m climbing I’m a rhyming apparatus”); not mentioned nearly enough is how good these cats were as rappers. Elsewhere, “It’s Tricky”’s hook has the words hitting as hard as the blocky 80s’ beat, and “My Adidas” is, of course, one of the first-ever successful fashion endorsements in rap music, but worthy of note is that Adidas lagged behind other athletic wear in Queens at the time until Run-D.M.C. made this song.

There is filler afterwards: “Is It Live” has the unfortunate task of following up that immortal four-song block which it simply can’t soldier despite the memorable drum programming; the hook of “Dumb Girl” doesn’t survive replays. There is good to be found in the second half, like the funky piano line of “You Be Illin’” while “Proud To Be Black,” where the rappers namedrops black icons, pre-dates the conscious movement of the Native Tongues by a few years.

#89. Brian Eno - Ambient 4: On Land (1982)

Inspired by a trip to Ghana where Eno captured the evening ambient into a microphone, Ambient 4: On Land, the last entry of his ambient series, combines natural sounds with synthetic ones, and then distills the results into bite-sized pieces; call them songs, even. For those reasons, it feels more influential than Discreet Music or Ambient 1 on modern ambient: some of these tones are appropriate for horror movie soundtracks, and you can even imagine some—like “Tal Coat”—appearing on Warp records.

Here’s George Starostin: “Most of his previous ambient albums focused on minimalistic keyboard melodies — short, meaningful phrases placed under a sonic microscope. On Land, allegedly recorded over a period of three years, was the first attempt to completely break away from that and go further, into the realm of sheer sonic atmosphere that is more hum and noise than melody. […] Above everything else, it would be interesting to see how Eno, a guy with a very traditional-emotional understanding of music deep in his heart, would handle such a transition to “non-melody”: and indeed, he handles it in the most melodic way possible.”

The Ghanaian night comes is immediately captured on “Lizard Point,” and from there Eno takes a walk to the shore on “The Lost Day, replete with the distant ringing of ship-bells as they search for land in heavy fog. “Shadow,” the first side’s closer and the shortest track here, is also the creepiest, with a ghost murmuring over the constant chirp of crickets that’s answered by some bass tones. The second side’s no less excellent: the tones that open “Lantern Marsh” are like a ghost reaching out while “Unfamiliar Wind (Leeks Hills)” features what sounds like the soft shuffle of feet slowed down over field recordings of animals, bringing to mind farms in Ghana. Both “Leeks Hills” and the closer “Dunwich Beach, Autumn 1960” have to do with decay, with Eno noting that “Leeks Hills is a little wood [that’s] much smaller now than when I was young, and this not merely the effect of age and memory,” while the closer references a seaport which a little Googling has told me has slowly eroded over time. Not another green world, but another world nonetheless, which makes more special than many of his other ambient records which couldn’t imagine a world that existed outside the airport or hotel lounge.

#88. Bruce Springsteen - Nebraska (1982)

Broadly speaking, like most artists getting ambitious, Bruce Springsteen put out a double album in The River, and then like most artists exhausted from sprawling out (and in Springsteen’s case, touring), he retreated by recording mostly acoustic songs on a tape recorder with the intention of fleshing them out on a later date. However, instead of recording them with his full band or in a proper studio (which he did attempt), he decided to ultimately present the tapes as is with only some additional echo to further increase the feeling of isolation. It’s Bruce Springsteen's most unique album, although I’m also aware it’s the Springsteen album to recommend for people who don’t like Springsteen: almost zero heartland rock to be found.

I’ll say this: Springsteen was never the best melodist, and when some of the acoustic backing is the same—a lot of fingerpicked arpeggios—it makes the songs sound the same (“Mansion” sounds like a lesser version of “Nebraska,” and “My Father’s House” sounds like “Mansion.”) The second half of this album engages the most when he brings out the electric guitar on the rockabilly throwback “Open All Night.”

“Nebraska” that opens this album is perhaps the bleakest song from this bleak decade, I make that declaration from the opening minute or so alone. The harmonica wails itself into existence, and when Springsteen finally starts singing he sounds so utterly defeated with no trace of that reliable boom in his voice as if he has been trudging around with no map of a place that he no longer understands (“I guess there's just a meanness in this world”). “Atlantic City,” with the chorused “Everything dies, baby, that’s a fact / But maybe everything that dies someday comes back” is a beacon of hope on an album like this; the opening cry of “Johnny 99” is reminiscent of the title’s track harmonica; “State Trooper” is an acoustic version of Suicide’s “Ghost Rider” with vocal screams that pull from “Frankie Teardrop.” All tremendous songs, but not enough to make this the best Springsteen album… just the best Springsteen album of the 1980s.

#87. Eric B. & Rakim - Follow the Leader (1988)

Rakim’s legacy is simple: he furthered the language of the most language-centric genre by introducing—perfecting—the concept of ‘flow.’ He had speed, yes, but he also had impressive control of breath and his own voice so that the words came out of him like liquid, whereas the rhymes from other major rap acts arrived like little grenade blasts. And within Rakim’s verses were arcane multi-syllables, internal rhymes, alliteration and other such weapons came natural to him. One of his inspirations growing up was the jazz saxophone, and he wanted to bring Coltrane’s method of improvisation into rap, “I couldn’t do that with a horn, but I could do that with a mic. I started thinking about my flows and asking myself, What would Coltrane do?”

Follow the Leader has their best songs at the start. The opener/title track surely ranks among rap’s best ever (“This is a lifetime mission, vision a prison / Aight, listen - in this journey you’re the journal, I’m the journalist / Am I eternal? Or an eternalist?”). And their beats are the best production that Rakim has ever rapped over. I think Massive Attack took notes on “Follow the Leader”’s momentum when they made “Unfinished Sympathy” while “Microphone Fiend” has the funkiest sleighbells since Miles Davis’ “Black Satin,” and “Lyrics of Fury” brings back the tempo with a trusty James Brown drum break and some heart-stopping screams. It’s a toss-up if this or N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton is more front-loaded.

The second half starts off strong with the orchestral-turned-jazz beat of “Put Your Hands Together” but then makes clear there’s no gas in the tank to even try to match the first three songs. One point goes to “The R” as that high-pitched synth line during the chorus—a sample of The Blackbyrds’ “Rock Creek Park”—likely flicked a switch in Dr. Dre’s head: dial up the luxury and we have g-funk. There’s three instrumentals, of which only “Eric B. Never Scared” is worth checking out for the scratching and sampling but goes on for way too long; “Just a Beat” and “Beats for the Listeners” announce their filler intentions with their titles.

#86. Metallica - Master of Puppets (1986)

It must have sucked to be a classic rock fan in 1986 watching all of the former legends make complete asses of themselves—with only one major exception; read on, dear reader!—but it must have been great to be a metal fan. This is Exhibit A. Here, Metallica take the template of Ride the Lightning—straight down to the acoustic introduction, another long instrumental, and another reference to Ktulu—but up the hook quotient (“Master! Master!”) and the epic-ness which is fitting for topics of drugs (“Master of Puppets”), insanity (“Welcome Home”), religion (“Leper Messiah”) and war (“Disposable Heroes”).

Whereas Ride opener “Fight Fire With Fire”’s acoustic introduction felt like a joke for listeners who bought what was clearly a metal album to be met with flowery acoustic guitar, “Battery”’s introduction’s deep notes evoke dread and the fills are still pretty. Then, it explodes, with no segue necessary: an electric guitar roads the chord, and the fill becomes a sear, and James Hetfield runs through the lyrics with a crazy speed. In between “Battery” and “Damage”’s baptism by thrash, “The Thing That should Not Be” uses an eerie guitar tone appropriate for a song inspired by Lovecraft; Cliff Burton’s guiding bass-line during the slower, middle stretch of “Orion” (the first time Burton gets a co-writing credit on the album is uncoincidentally the first time he’s the best part of the song, and he’ll be sorely missed when he passed away from a bus crash that same year); “Master of Puppets” has a sudden instrumental stretch which really does sound like a drug high.

There isn’t a single song here that runs shorter than 5 minutes, and yet, the songs don’t feel that long. This is sharp contrast to the following …And Justice For All where the get even more epic but I start checking my watch during songs, or The Black Album, where they simplify and get boring. Here was the rare band that was getting more popular despite songs becoming more complicated, and even rarer was that a metal band dominated pop music during the years of 1983 and 1991 so thoroughly.

#85. Scientist - Scientist Wins the World Cup (1982)

With ten tracks all titled “Dangerous Match,” a title like this one, and a cover of the Jamaican soccer team—that didn’t qualify that World Cup that year—dominating England 6 to 1 to a packed stadium, you’d think you’d need at least a little bit of soccer appreciation to like this. Not at all, and it’s kind of disappointing that none of the sound effects are lifted from the game: no cheering audience, no sports announcers, no satisfying thud between the cleat and the ball. Especially when you consider the effects that made dub genius Hopeton Overton Brown’s 1981 album Scientist Rids the World of the Evil Curse of the Vampires so attractive. Real talk: Scientist’s work in the early 80s are all tremendous from what I’ve heard, and I'm not sure how anyone can say definitively that any one album is that much better than any other album. I know I can’t, but I can say that I simply just play this one more.

Anyway, dub’s ideology of further bringing out the rhythms of reggae, deconstructing the rest of it, reshaping and then re-adding is fundamentally no different than the remixes of DJs within the electronic space, and even taking parts of what you like and emphasizing them is just a hair away from sampling. Come for the bass-lines, yes, but stay for the textures, which can be hooky, jazzy, bluesy, and even jangly, and the drums thumping hard because of the amount of echo that Scientist applies to them. What an appropriate cognomen, passed down from King Tubby himself! He truly was a mad scientist.

Despite the fact that none of the tracks are properly titled, don’t let anyone try to tell you that all of these songs sound the same: the exaggerated echo applied to the bass-line of “Match 1” makes it feel much more digital than the rest of these songs; the bright horn lines give “Match 2” a jazzy feel; “Match 6” has one of the most addicting bass-lines ever, and “Match 10” brings in cowbells. They reissued this album in 2016, under the name Junjo Presents Wins the World Cup which also adds the original version of the songs that Scientist pulled from which is a boon to have so you could hear just what Scientist does.

#84. David Murray - Home (1982)

Had David Murray been born just two decades earlier and been active in the avant-garde jazz scene of the 1960s, he would no doubt be revered as one of the great post-bopists. Alas, we’ll have to make do with calling him one of the best of the post-fusion modern era, but also one of the most hard-working musicians ever: when you add up the studio and live albums under his own name and under different bands, he’s released some 150 records and shows no sign of slowing down despite pushing 70, and his latest album, Francesca, is secretly one of the best jazz albums of 2024. When he assembled his short-lived octet, he made some of the best work in the style of Charles Mingus since 1972, a band that was a who’s who of modern avant-garde: Henry Threadgill (alto saxophone), Anthony Davis (piano), Lawrence “Butch” Morris (cornet), Olu Dara (trumpet), George Lewis (trombone), Wilber Morris (bass) and Steve McCall (drums).

Ming is typically the more-celebrated of his octet recordings, but I strongly prefer Home for the title track, where these avant-garde players knock out one of the decade’s best jazz ballads. I’m already swooning from Anthony Davis’ impressionistic introduction, and then David Murray traces past Mingus to Duke Ellington with the counterpoint-filled composition. Murray’s solo that begins at the 3:15 mark, full of rich, wavering tones is tremendous, and the song’s melody would’ve easily been a new standard had this been released circa 64. The next song, “Santa Barbara and Crenshaw Follies” emphasizes the big band nature of the octet, and the way the horns act during the louder sections recalls Mingus’ “A Foggy Day” when Mingus manipulated saxes to sound like streetcars over Wilber Morris’ constantly active fingers and Steve McCall’s extra drumrolls. “Choctaw Blues” doesn’t sacrifice the group’s avant-garde tendencies despite the more profound blues influence: Wilber Morris comes in with a bowed bass thirty seconds in that sounds like it doesn’t even belong in the same song, letting the notes hang in the air before Morris starts sawing away.

The second side’s only made up of two songs. “Last of the Hipmen”—what an appropriate title for this band—has Wilber Morris and Steve McCall absolutely killing the rhythm, with McCall switching from a skitter to a combination of colourful cymbal taps and slashing drums, culminating in his drum solo near the end. Joining the two is Anthony Davis, whose positively jovial chords somewhat recall Red Garland here. Closer “3-D Family” bursts with energy in the big band arrangement that maximizes the horn players, backed by the surprise of bongos from Steve McCall. After Home, the octet would undergo line-up changes and hiatuses and never re-capture the fire of these first few records.

#83. Youssou N’Dour - Immigrés / Bitim rew (1984)

Youssou N’Dour gets my vote for the best musician from Africa because he sings magnificently and because he put out great work even decades removed from his prime, where, somehow, not a single crack marred his soaring voice. This 5-song cassette recorded in Paris in 1984 is before he became an international superstar—before he linked up with Paul Simon and Peter Gabriel—which means there’s none of that icky and sometimes disastrous crossover attempts that found their way into his albums from 1989-94. Instead, it’s just his voice and his band Le Super Etoile de Dakar laying down thick mbalax (Senegalese rhythmic pop music) grooves. For the record, I considered The Lion for this list, but it just misses the mark because of too much Peter Gabriel and slap bass, both things not what I want in a N’Dour album, although it’s a masterpiece compared to The Guide (Wommat). Somewhere in the 101-150 slot, for sure though!

The multiple percussionists of Le Super Etoile de Dakar, playing on different drums ranging from the Cuban-originating tumba to the West African-native tama (“talking drum”) and sabar lay down chunky and engaging rhythms throughout, but shining bright alongside the vocals is lead guitarist Jimi Mbaye, whose guitar lines function like slippery gold. It’s Mbaye that elevates the title track during his solo midway through, while also doing a call-and-response dance with the vocals early on in “Taaw.” Meanwhile, the two saxophonist—Rhane Diallo and Féfé David Diambouana—are tasked to add additional textural density and extra melody on “Badou” and “Autorail.” (If you’re one of those losers that only uses Spotify for music, then you won’t find the latter there.)

“Pitche Mi” is the best song here, slowing it down and removing much of the dense rhythms of the rest of the album. The saxophones are reminiscent of the trumpets that backed Al Green in how they mostly resort to bold one-note blasts. All that being said, I suspect his best album wouldn’t be for another two decades, making N’Dour one of the very rare artists that broke through but wouldn’t put out their best work until much later.

#82. N.W.A. - Straight Outta Compton (1989)

It’s either “Follow the Leader” or “Straight Outta Compton” that gets my pick for best rap song of the decade depending on if you prefer masterful flow or production, respectively. You bring home a CD with a bunch of serious-looking motherfuckers looking down at you, you hit play, and you’re greeted with an innocuous statement: “You are now about to witness the strength of street knowledge.” And then, Ice Cube curb-stomps you, “Straight outta Compton, crazy motherfucker named Ice Cube,” and it just doesn’t relent. Early Ice Cube was a force of nature, and while it’s true that his rhymes are quite simple (“tool” rhymes with “fool”; “duck” with “fuck”), each one hits like a sawed-off. Meanwhile, Dr. Dre’s production is might his best work: chicken-scratch funk and sustained horns; it’s like hearing him works towards both 2001 and The Chronic simultaneously. And the chorus! A car screeches to a stop, someone yells out “GO!”, and a woman screams—in ecstasy? in fear? both?—and that ambiguous sound gets looped, bounding us into the next verse.

As is the case of “Follow the Leader” for its album discussed earlier on this list, nothing else on this album comes close to matching “Straight Outta Compton”’s intensity or even musicality. There’s a huge drop-off after “Express Yourself,” and no one needs the remix of “Compton’s N the House,” with the too-sparse beat highlighting that the drum programming was probably dated by ’88 (MC Ren’s “Yella boy on the drum getting dumb” is all too true, but not in the way he meant it). The CD version, now the standard, comes with three tracks: “8 Ball (Remix),” “Something Like That” and “Something 2 Dance 2”; none of them essential, although the latter two are better than the aforementioned remix (Arabian Prince was more famous than any of the other N.W.A. members at the time, who stepped down when he realized that the group wanted to go more “Fuck Tha Police” than “Something 2 Dance 2”).

That said, there’s lots of funk to be found within “Gangsta Gangsta” and “If It Aint’t Ruff.” “Fuck Tha Police” feels like a great statement and less a great song, especially when the scratched blasts of the beat have to sustain interest for 6 minutes, and I appreciate Ice Cube selling the close rhyming “narcotics” and “product” by having his voice trail off. Fun fact: J Dilla has a single named “Fuck the Police” that’s one of the producer’s rare times he takes the microphone. I wish I could say it’s the better song, but it’s closer than you’d think. Dr. Dre is funnier than he’ll ever be again, as he tries to convince us “Yo, I don’t smoke weed or mesh / Cause it’s known to give a brother brain damage” just a few years before making back-to-back weed classics, but “Some drop science, well I’m dropping English” and “MC Ren, will you please give your testimony to the jury about this fucked up incident?” are genuine laugh-out-loud moments that become rarer in his own discography as the depictions of sex and violence get out of hand as early as they would on follow-up Efil4zaggin.

#81. Jane Siberry - The Walking (1988)

Toronto-born, Etobicoke-raised Jane Siberry built up enough traction and goodwill over the course of her discography to have her 1988 album, The Walking, be released internationally via Reprise Records. Rather than doing what one might expect of her, Jane Siberry did what she wanted to do instead, which was compose an art pop opus that remains the closest thing any Canadian musician has come to Kate Bush. Canadian music website Dominionated’s review of the album notes that “The Walking was nowhere to be found on Toronto’s taste-making CFNY 102.1’s crowd-sourced best of 1988 list after No Borders Here came in at 10 for 1984 and The Speckless Sky peaked at 19 in 1985,” and the Toronto radio station felt that there was no song on the album that was viable for airplay, even though some of the songs here are stronger, and catchier, than local hit “Mimi at the Beach,” which they helped champion in the first place.

Sure, some will have issues with the choruses’ evocation of the Cowboys and Indians game within “Ingrid and the Footman,” but the song’s bigger issues are that the wordless vocal sections feel born out of Bush’s “The Big Sky” without nearly enough physical weight, and the verses are far too short to say much about the failed relationship. But otherwise, I find this album charming, especially as she sorts out the feelings of her breakup with album producer John Switzer on the choruses of the title track, the melody climbing in resolution to “There’s nothing that I will take back” and then dissolving into a falsetto to coincide with her confidence trailing off. Closer “The Bird in the Gravel” is the closest anyone has come to Nursery Cryme-era Genesis as she sings from the perspective of different characters like a one-act play; best of all is when she sings from the point of view of a kitchen pantry around 3 minutes in to shimmering synths.

There’s a section on “The White Tent the Raft” that I play, I dunno, fifty times a week: it gives me life. It happens between the 3:23 to the 3:39 mark where she sings short lines with a coy smile and playful falsetto—“50 bucks, and that’s all you’ve got?” she sings, as if to say 50 bucks is plenty, because, as she tells you, “Yeah, I love you, I love you a lot”—that’s answered by an even higher-pitched reedy synth sound. And you never hear that melody or that sound again on the song, because this thing, this strange and mystical “White Tent the Raft”—no explanation given beyond “There’s a white tent that sits in the middle of a raft / That floats down / Floats down the middle of a river”—stops for no one.

Well, I'd maintain that much of Sun Ra is a matter of personal taste and saying he released A BUNCH of bullshit is just a gross misrepresentation. My experience as 30 odd year long fan is that there's always something of interest on his albums and (so far for me) no bullshit. I even like the squeaky door. That said, this is the start of an unusually thought provoking and informative list. The breadth of genres alone is amazing. I hope it continues up the list. And finding that particular Fela record in this particular February was...satisfying.

Holy shit, it's back! Looking forward to seeing what's new, and what's changed about the old stuff - lots I remember moving *down* the list is promising. Good to see N'Dour appear, love that guy - if I were to make these lists (And I'd love to at some point!) he'd be a shoe-in for the 80s, 90s and 2000s. I remember seeing a whole bunch of African stuff being recommended for inclusion in the comments section of the old version, which is how I discovered Omona Wapi and Synchro System, but not how I discovered Orchestra Baobab's Mouhamadou Bamba (one of my favourite records!). I'm sure you're aware of all these, so I'm interested in seeing what appears and what doesn't, and learning why, over the coming weeks. Great follow-through on making the 50th post a big one :)