I’ll never put these words behind a paywall, but I’ve set up a Ko-fi page for anyone who likes my writing enough to donate some money towards a coffee or my 2025 wedding.

(100 - 81)

#80. Chiemi Manabe - Fushigi Shoujo (1982)

The world has finally caught up to city pop, Japan’s disco-inspired luxurious pop music of the late-70s and 80s, but techno kayō/technopop from around that same period hasn’t enjoyed nearly as much international attention. If only they sang more in English like so much city pop did? Or maybe it’s that the quirked-up synths aren’t nearly as enticing as getting to hear disco all over again.

This is an album stacked with incredible collaborators, including YMO’s Haruomi Hosono, guiitarist Kenji Omura, saxophonist Satoshi Nakamura (who’ll go on to work with Tatsuro Yamashita), Masayoshi Takanaka drummer Tatsuo Hayashi, Akiko Yano and EPO as lyricists, among others. You could criticize Chieme Manabe for being a blank slate vocalist that simply has to navigate these lyrics and arrangements that other people have given her, but these composers gave this girl some of the craziest sounds available at the time! If you want to hear what I mean, just listen to the opening 20 seconds or of third song “不思議なカ・ル・ト” where a synth giddily jumps around in one of the most addicting sound-bytes of the decade. Or check out “うんととおく” with its strange percussion textures—like a frog jumping around on digital lily pads—while the synth line sounds like the machine is on its last battery cell. Only closer “Good・by-Good・by” sounds generic by these standards, and perhaps announces so given the sentiment and the fact that it’s the only song here with a fully English title.

This album was destined for obscurity: the title translates to “Mysterious Girl,” and in mystery Chiemi Manabe will remain. It was her only album, released in the same year she starred in Hiromichi Kawakami’s film Summer Secrets, and she never released in any other music or appeared in other films after that. It’s not on Spotify either (but available in full on YouTube). It’s a shame because at its best, this album sounds like a cross between the electronic music of the 1970s backing girl group music from the early-60s, which means it was tailor-made for this krautrock and girl group-loving fanatic.

#79. Eberhard Weber - Later That Evening (1982)

Stuttgart-born Eberhard Weber customized his bass to add a fifth string which enabled him to play more expressively as he moved the instrument from a rhythm instrument in the background to lead: that was his contribution as crudely as I can sum up in the world of jazz bass. What I like about him is that he adopted ECM’s chamber aesthetic without sacrificing composition: he wrote some very interesting songs, and two of his best are included here. Disbanding the Colours Quarter after Little Movements, Weber wasted no time in testing out a new configuration: Bill Frisell on guitar, Pat Metheny pianist Lyle Mays, Paul McCanless on reeds, and Michael DiPasqua on drums. There’s way less fusion than on the previous the previous album which is to be expected: the previous saxophonist and drummer came from progressive rock backgrounds, which is not true of this new quintet (although, of course, Frisell would play everything with John Zorn shortly after this, and speaking of Zorn, I would have liked to have included Spillane on this list—one of the first jazz albums I ever heard—but ultimately couldn’t justify it.)

Mays leads opener “Maurizius” with a simple piano figure that sounds like he lifted it straight out of the romantic era, and it reminds me of what Red Garland did for Miles Davis on “It Never Entered My Mind”: don’t overcomplicate and just go for the prettiest chords you know. The additional melodies from McCandless and spacey textures from Bill Frisell shortly after Mays’ improvisation peaks are icing on the cake. I took the song out recently to a gentle snowfall, and that seems to be the best setting for it.

“Death in the Carwash” is even better, establishing a sense of unease through ghostly voices and DiPasqua’s restless cymbal work, pondering just how long this band could hold that tension before releasing it. Almost 10 minutes, it turns out, which is when Frisell starts improvising and guiding the rest of the band towards the drawn-out climax. Alas, the second side isn’t nearly as special, with Weber’s “Often in the Open” sounding too much like a first pass at “Carwash” in the sense that it’s another slow burn to an eventual climax, but not nearly as captivating. Meanwhile, “Later That Evening” ends the album with an ambient miniature (well, comparatively; it’s almost 7 minutes, but bite-sized compared to the previous three songs), and resolves a little too nicely when McCandless states the melody around 5:30 and carries the song out.

#78. Bad Brains - Bad Brains (1982)

Washington band Bad Brains formed well before hardcore, and were actually active around the same time that punk broke, but back in 1976, they were operating under the name Mind Power and making jazz fusion. When then-singer Sid McCray introduced them to punk rock, they realized they had the technical chops to out-play these bands and promptly switched genres. (McCray left soon after, replaced by H.R. when the band became Bad Brains.) It was never a matter of ‘merely’ keeping in time in maelstrom tempos, which guitarist Dr. Know, bassist Darryl Jennifer and drummer Earl Hudson did no problem, but adding groove and flash to hardcore.

What further separated them from American hardcore was their love for reggae, inspired from seeing Bob Marley live. It’s true that reggae had proliferated punk music across the ocean, but that was not yet true of American punk. Thus, unlike other hardcore albums which can feel ‘samey,’ Bad Brains lets you take a breather with three much slower reggae cuts disbursed throughout. But “Jah Calling,” “Leaving Babylon,” and “I Luv I Jah” don’t feel like mere imitations of a hardcore band trying their hand at another genre precisely because they weren’t a hardcore band to begin with.

But it’s the hardcore songs that are the best regardless. Opener “Sailin’ On” has vocalist H.R. snarling “You don’t want me anymore”—still only the third-best opening to any hardcore release I can think of; the other two will come shortly on this list—and then looking ahead to better days, “So I’m sailing on, yeah, I’m sailing on” he says as his band’s carry him away from heartbreak. Unlike other hardcore bands, H.R. was an optimist, hence those choruses, or “Attitude,” based on Think and Grow Rich that his father leant him. Dr. Know’s guitar on “Don’t Need It” is absolutely filthy, and of course, single “Pay to Cum” does something that not even most rappers have figured out: how to shove 27 words in 4 seconds. The album sounds like shit, especially compared to other hardcore bands around this time, but as Bad Brains would prove out on future albums, that turned out to be part of the charm.

#77. Pylon - Chomp (1983)

Athens post-punk group Pylon was the Golden Mean of the other two, much more popular groups from Athens active at the same time: they mixed the danceability of the B-52’s (who they toured with) and the shamanistic, half-jangle/half-propulsion of R.E.M. They never got their dues. Their off-kilter instrumentals are better than that of Gang of Four, while vocalist Vanessa Briscoe Hay twisted, shouted, and writhed in controlled abandon. On “Crazy,” she leaps off the end of a line and into the next during the “Shaking” part making you feel, well, a bit crazy as you try to follow the thread of one body part shaking because another is shaking because the earth is shaking. The overdubbed “I’m not…crazy” sounds like it’s being sung by a complete madwoman, trying desperately hard to convince some authority figure of their sanity. Compare her performance with Michael Stipe on R.E.M.’s cover of “Crazy” and it highlights just how special she was.

Dig the slow-burn start of “K” that opens the album, with Curtis Crowe’s deliberate cymbals opening space for Michael Lachowski’s brooding bass-line before Crowe subtly picks up the pace for Randy Bewley’s buzzing guitar weaving in and out of that rhythm. And then Hay just knocks it out of the park, as if she’s refereeing some game “Mamamamama 10 POINTS”; “Ohhhhhhhhh twenty-two!” Elsewhere, note Bewley’s Talking Heads-like guitarwork on “Beep” that makes me wonder what might have happened if Brian Eno happened onto them (they did tour with Talking Heads); the bass-line of “M-Train,” which hits like, well, you know; the male backing vocals of “Buzz” which sounds like they came out of a low-budget martial arts film.

One quibble: the album was produced by the dB’s Chris Stamey, and Gene Holder, and engineered by Mitch Easter (responsible for much of R.E.M.’s early magic), I wish Easter and the team was able to coax more of “Crazy”’s jangle out of them, or that more songs had the brightness of “No Clocks,” the catchiest song here. But regardless, there are actual songs here compared to say, ESG’s more rhythmic and dryer Come Away With Me that same year.

#76. Prince Far-I and The Arabs - Cry Tuff Dub Encounter Chapter III (1980)

It’s a fool’s errand to try to explain what makes one dub record so much better than another dub record because language only goes so far, and there’s only so many times I can type some variant of “the bass and the drums thump hard” without being redundant. But within this record is the best-ever dub song that I’ve heard, “Shake the Nation.” A heavily-treated drum-roll lasts half a measure but perks your ears up for the ensuing organ that gives us the feeling that Prince Far-I is about to take us to church, which becomes the reality when a female vocal comes in singing his name and telling us that he’s going to “Shake the nation.” From there, it’s full dub ahead as the, oh why bother looking for a synonym, the bass and the drums thumping hard, and the other effects—underwater keyboards and razor-sharp guitar—keep piling on. Anyone unsure if they could be a ‘dubhead’ needs to be baptized by this song, and if it helps, punk fans ought to recognize the Slits’ Ari Up among the backing vocalists here.

Alas, nothing else on this album comes close, but the way I see it, no other dub song does either, but what’s strange is that there’s so many instruments piled into “Shake the Nation” whereas that’s not true of many others here. The Pressure Sounds reissue of this album notes that Cry Tuff Dub Encounter Chapter III “was racked out in rapid studio time, conforming with the can-do ethics of the time - not to mention the lack of cash,” and maybe that’s why.

I’ll say this, only time-filler “Plant Up” where neither Prince Far-I’s bassy vocals nor the cheesy dub effects are attractive enough to warrant 4 minutes, let alone twice that, is a miss. Prince Far-I sings again on short closer, “Mansion of Invention,” “Nuclear weapon is a disease / Atomic bomb is a sickness.” End your album with an important message! And then some more dub for good measure.

#75. Jack DeJohnette’s Special Edition - Album Album

Perhaps best-known for his work on Miles Davis’ jazz fusion years, drummer (and later pianist) Jack DeJohnette is one of the best in his field, and one of the hardest-working too: he appears on more ECM albums than anyone else, and has put out tremendous work even in his 70s; a list of the legends that he’s worked with besides Miles Davis would fly off the page (and remind me of the Gary Giddins’ chapter on Art Blakey where he named musicians that Blakey helped mentor). In the early 1980s, DeJohnette assembled the Special Edition to prove out another talent, that he could also be a great bandleader and composer, whereas his previous albums were more about technical chops or ECM aesthetic with fewer players.

Special Edition’s debut in 1980 contained loving tributes to Eric Dolphy, John Coltrane and Sun Ra and I didn't think it could possibly get better than that until this album rolled around 4 years later. The only other band-member that came over from Special Edition is David Murray on tenor saxophone, mentioned earlier on this list; replacing Peter Warren on bass is Rufus Reid, replacing Arthur Blythe on alto saxophone is John Purcell, and they’re joined by Howard Johnson on tuba and baritone saxophone to add a big band feel to these songs that are a tribute to DeJohnette’s mother who had passed away around this time, with “New Orleans Strut” dedicated to his father that’s a cheeky take on the city that birthed jazz by incorporating synths and drum machines (the cover depicts DeJohnette’s family).

Album Album joyfully bursts out of your speakers as soon as you hit play with a theme first on sax, accented by DeJohnette, and then a klezmer-like melody that plays like a kid on a candy high. But whereas “One for Eric” also started with a rollicking theme, it stalled during the improvisations while trying too hard to invoke Dolphy’s casual weirdness. By contrast, the solos here keep up the bubbly momentum, which is true even when DeJohnette switches to keys (not his strong suite, but something he loves doing regardless), and what a smooth transition from the saxophone solo into the piano solo! Many of these songs are in the vein of “Ahmad the Terrible,” by which I mean plenty of major-key themes played in singing, staccato tones. The album is never languid because it’s hard to think that adjective would ever describe an album with DeJohnette on drums. He has such a distinct style when he’s on the cymbals and gets to show off some chops during a rapid-fire solo on “Festival.” A childishly happy album, this one, so it’s a shame I spend too much time as a cynical adult.

#74. Steve Roach - Structures From Silence

The way ambient composer Steve Roach tells it, he’s spent his entire formative years in immersion. First as a child in southern California surrounded by nature. Then as a teenager working in an independent record store with access to the Berlin school records, and the long, expansive synth soundscapes from Tangerine Dream and Klaus Schulz. Then as a motocross racer. The latter doesn’t seem important to his music, but he disagrees: “There’s a real kind of discipline you have to have if you’re going to do it fully; you have to be fully awake and present […] Your life depends on it. All of those things relate right over to what would become my path in music.”

1984’s Structures From Silence was a breakthrough for him by dropping the beat entirely. An obvious point of comparison would be Brian Eno, but Eno’s ambient have rarely felt as holy as do the ones here—which one major exception, which would score high on a songs list of the decade—where the reverberated synth notes can feel like choral voices with a synthetic glint. That, and Eno’s earliest ambient music was made for the intent to listen to on the background; Structures From Silence will do the trick there, yes, but Roach wants to suspend you, the listener, and time. “The pieces on this album were created from my sole (soul’s) desire to live within a sonic space that would provide a sense of safety, soul nurturing comfort and time suspension,” he said in the liner notes of the album’s reissue. And the best way to get that experience is being, well, fully awake and present.

On “Reflections in Suspension,” the sequencers gently pulse and seem to communicate with one another, as you might imagine stars on a quiet night, and the cresting of the half-melody at 4 minutes in feels huge. On “Quiet Friend,” what little crescendos of the previous track are reversed as the synths move in a slow fade towards the end of the first side. And though the title track—spanning literally half of the hour-long album—is too little too long, it’s still pretty enough to immerse yourself in.

#73. Lou Reed - New York (1989)

New York is Lou Reed’s second-best album, ever-so-slightly overrated because it has the cardinal sin of not just one, but two ‘c’-words that critics love. (1) It has a very loose concept, and (2) it was released in 1989, the year of the comeback alongside Bob Dylan’s Oh Mercy and Rolling Stones’ Steel Wheels. (Oh Mercy is okay. Steel Wheels sucks ass.) In general, it’s his longest album since Metal Machine Music and that’s not deserved; you can scotch the last three songs without missing much (“Strawman” especially is a 6-minute tirade about nothing at all).

That being said, “Dirty Blvd.” is the latest in the long lineage of “Sweet Jane” imitations from Lou, but it’s also one of his best songs; the G and D chords are, for once, the best-sounding G and D chords his band has cooked up since The Blue Mask. “Halloween Parade” is even better than that, a tremendously sad song that never feels sad, similar to “Walk on the Wild Side”: it isn’t until the backing vocals come in that you realize how devastating the song really is, like the voices of his friends all departed from the ongoing AIDS epidemic singing along with Reed. Fred Maher, once a machine, actually adds a jazzy snap to that song.

Lou Reed is in fine form throughout the album, not forcing casual observations about his beloved city to be poetic and achieving a more natural poetry as a result. “Caught between the twisted stars / The plotted lines the faulty map / That brought Columbus to New York” is how the first song starts and “And something flickered for a minute / And then it vanished and was gone” is how it ends; “Dirty Blvd.” has the ambiguity in the rather simple line, “[Pedro’s] father beats him because he’s too tired to beg,” making you ponder who is too tired—Pedro, or his father—and knowing the situation is hopeless either way.

#72. Tom Waits - Swordfishtrombones (1983)

NME ranked this as second-best album of the year, below Elvis Costello’s Punch the Clock, which is about as wrong as you can possibly be. This is a weird one, and it truly does earn its strange name. It’s an album of many firsts for Mr. Waits: his first to be self-produced, his first not on Asylum, his first since marrying Kathleen Brennan who would turn out to be his muse and frequent collaborator (Heartbreak and Vine was recorded before they got married, even if got released after), and his first entry in his 80s’ trilogy, with Rain Dogs and Franks Wild Years.

Famously, Brennan would be the one that introduced Waits to the insane blues of Captain Beefheart, whose twisted delta blues of Safe as Milk appear throughout the album, but equally important to this record is the influence of composer Harry Partch. (Uou might recognize the name because he was invoked in a very odd beef between Fiery Furnaces, Radiohead, and Beck, all when Fiery Furnances’ Matt Friedberger thought Radiohead’s tribute to WW1 veteran Harry Patch was a tribute to the composer.) Francis Thumm, credited for the arrangements, metal aunglongs, and glass harmonica, was the one who likely introduced Waits to the composer, having played in the Harry Partch Ensemble himself. It’s Thumm’s additional percussion tones that make “Underground” and “16 Shells From a Thirty-Ought Six” extra special. (“There’s a world going on underground” summed up much of the best music available in the decade.)

The names and places makes the album feel conceptual, but all of Tom Waits’ songs are ultimately stories of this strange thing that is America. Especially noteworthy are the short and lovely “Johnsburg, Illinois” where we get to hear Tom Waits compose a short love song to his new wife (the title is a reference to Brennan’s birthplace), sung with his most vulnerable and most human voice on the album, and “Frank’s Wild Years,” a short detective fiction (“He hung his wild years / On a nail that he drove through / His wife’s forehead” is how it starts, and tell me you’re not drawn in immediately from the violence). Even “Dave the Butcher” feels like a character study given its name despite the fact that it’s an instrumental. Best of all is “Shore Leave,” taking some of the textures of “Underground” but thrusting them to the busy streets above ground. When he starts singing the title words at the end over and over in a voice that’s on the cusp of breaking, it might be his best-ever vocal performance.

#71. Akiko Yano - Tadaima (1982)

Born in 1955, Akiko Yano started playing piano at the age of three because her mother wasn’t able to pursue the same opportunity due to World War II. She soon fell in love with jazz, and forced her father to take her to jazz bars and would eventually uproot herself to move to NYC to play with jazz legends Charlie Haden and Pat Metheny, and it’s very clear that she would have pursued jazz had it not been for Yellow Magic Orchestra. She dated and married (and later divorced) Ryuichi Sakamoto, and was asked to be YMO’s keyboard player on tour, introducing her to sequencers and temporarily pulling her out of the jazz world and into synth pop music. “Looking back, my time with YMO ended up becoming one of the pillars to my own music,” she recalled.

She got a hit in 1981 thanks to a cosmetics commercial but she had her own plans for follow-up Tadaima. “Tadaima became a combination of everything that I wanted to do, including putting music to children’s poems! The record company didn’t want me to make something that experimental, but I did it anyways! I was very influenced at the time by the wave of English bands that were beginning to arrive in Japan.” It’s that experimental spirit that makes it more appealing than most other techno kayō albums from around the same time; that, and Yano’s simply a far more gifted melodist anyway. Only the nine-song medley that takes up 9 minutes misses the mark which might be because of the language barrier, and more textures like the marimba might have helped.

To sweeten the deal, she’s brought her YMO pals along with her: Ryuichi Sakamoto adds in ringing telephones to quirk up the irresistible playground melodies of “ただいま。” while Haruomi Hosono (and even the venerable Kenji Omura) help out on “春咲小紅.” For example, “Vet” is a thrashing electronic punk song that was very rare for ‘81 (you’ll hear some similar speed in Dieter Moebius’s post-Cluster records from Germany around this time, but not in a 2-minute injection), while the percussion-heavy closer “Rose Garden” has a detour that makes it feel like we entered Kate Bush’s The Dreaming. Alas, the experimental bend of Tadaima evaporated for follow-up Ai ga nakucha ne which is a shame because the collaborators get even better on that album, including Ryuichi Sakamoto and all of the members of Japan.

#70. Lucinda Williams - Lucinda Williams

This is a PSA that Lucinda Williams didn’t just hand in one great album near the end of the millennium, she made several. “The L.A. people said, ‘It’s too country for rock.’ The Nashville people said, ‘It’s too rock for country,’” Williams said about her third album released after a near-decade hiatus after her first two albums. Lucinda Williams found a home in the most unlikely of places: indie label Rough Trade, known best for punk rock, but whose founder Geoff Travis recognized that Lucinda Williams wrote “with the wit and humor of real rock ‘n’ roll.” This album’s influence is well-documented: “Passionate Kisses” would later be covered by Mary Chapin Carpenter (whom nabbed a Grammy for Best Female Country Vocal Performance for it); Patty Loveless covered “The Night’s Too Long,” while Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers did “Changed the Locks,” picking the song with the most rock swagger here.

Like Emmylou Harris, Williams’ voice is sometimes doing most of the heavy-lifting, and she’s almost able to salvage “Abandoned” from its metronomic drumming. Don’t be scared of the country clichés on “The Night’s Too Long,” where she takes up a third-person narrative about a woman named Sylvia who eventually moves out of the country, away from “small town boys [who] don’t move fast enough.” That last verse is a marvel of specificity, “They just met / And his shirt’s all soaked with sweat / And with her back against the bar / She can listen to the band / And she’s holding a Corona / And it’s cold against her hand” (note the contrast of hot and cold). But she’s also blessed with a great guitarist and foil in Gurf Morlix, who would continue to work with her through to her masterpiece Car Wheels on a Gravel Road. He anchors “Am I Too Blue” (“When I cry like the sky, like the sky sometimes, am I too blue?”) with hooky fills and gets in a pedal steel guitar solo, while his electric guitar on Howlin’ Wolf cover “I Asked for Water (He Gave Me Gasoline)” traces country’s history to the blues.

The best songs are the side openers. Christgau points out the hook of “I Just Wanted to See You So Bad” is repeated nine times out of the song’s total 21 lines (a trick she'll re-use for West highlight “Are You Alright”), making it this hooky and romantic little darling of a song. Love the casual evocation of the Shirelles’ “Baby It’s You” (compare “It didn’t matter what my friends might say / I was gonna be with you anyway” to “It doesn’t matter what they say / I’m gonna love you any ol’ way”). “Passionate Kisses,” on the other hand, actually has a jangle to it, solidifying the relationship with her new label who had been investing in that sound.

#69. Hiroshi Yoshimura - Wave Notation 1: Music for Nine Post Cards

Consider this is the actual follow-up to Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports—pure sound colour—that Brian Eno himself had already moved past; as discussed earlier this list, that same year, he was looking to combine natural sounds with synthetic ones on Ambient 4: On Land. Another title, then: Ambient 2: Music for Museums.

While composing Music for Nine Post Cards, Hiroshi Yoshimura visited the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, a private mansion-turned-international embassy building, and then subsequently converted into a museum in 1979. The visit had a profound effect on the creation of this album, where he imagined what kind of music might fit the interiors of such a building, and then he asked the museum if Music for Nine Post Cards could be used as soundtrack music for Hara, to which the museum agreed. And when museum visitors inquired about the music, it prompted Hiroshi Yoshimura and Satoshi Ashikawa—founder of Art Vivant, a record and book store that was one of the first to import Brian Eno’s ambient records—to launch a record label for the express purpose to release Music for Nine Post Cards.

Like early ambient Eno, Hiroshi Yoshimura’s music at this point in marked by its austerity. The beauty is its tones, the melodies incidental and the harmonies barely there, often just light use of drone for the low-end. It’s the best Eno-Budd collaboration ever, and the Fender Rhodes actually does have a natural Budd-like “ripple in slow motion” effect. As suggested in the title of centerpiece “Dance PM,” the tones do actually dance a little, and so it’s no surprise that Yoshimura would make a dance album of sorts next decade in Face Time; “Urban Snow” because it contains vocals buried deep down in the mix (“snow…snow…”), as if a tape recorder caught a trailing voice off in the background while “Dream” has Yoshimura switching from the Fender Rhodes to a synth for the lead instrument. All told, I like music for museums more than I do airports.

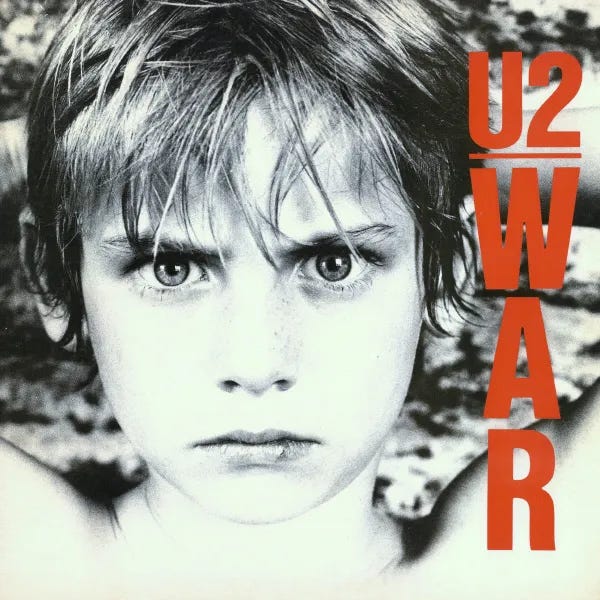

#68. U2 - War

A top 3 post-punk album of its year, which would only sound strange if you are only familiar with the U2 of 1987-onwards when they had completely abandoned post-punk. From their inception to 1984, they were a post-punk band, and while we still got some great music here and there afterwards, it’s almost a shame that they linked up with Brian Eno because I can’t help but wonder what would have happened if they kept on making albums in the vein of War. More respect among general listeners, that’s for sure.

Steve Lillywhite really needs more credit for his production work in the early 1980s before he lost his mind on Rolling Stones’ Dirty Work. He had a major hand in popularizing the gated drums through his work with XTC and Peter Gabriel, and for U2, he ensured that the Edge’s guitar crunched while allowing the two U2 members with last names, bassist Adam Clayton and drummer Larry Mullen Jr., room to declare themselves. (After 1992, Clayton would never clock in his hours ever again.) In that regard, I liken this album to the Smiths’ Meat is Murder: both albums have the bands’ least-important members doing their most important work. To wit, “Sunday Bloody Sunday” is pure thrust thanks to Clayton’s bass, a gutteral roar, and drummer Mullen’s rabble-rousing beat to the point that I genuinely wonder if the Edge is the least integral part of that song.

The Edge redeems himself later on “New Year’s Day” and “Two Hearts Beat as One,” whose rhythmic chicken-scratch guitar—an approach that he basically completely abandoned around ‘87—reminds me of Jerry Harrison’s early work for Talking Heads (i.e. before they met Eno as well). And while it’s true Bono only has one good mode—anthemic—it helps that the majority of War are anthems, and he only gets overwrought when they quiet it down, especially on “Drowning Man,” where he improvised being “Van Morrison, wailing away.” There are some welcome additional instrumentation: the electric violin screeches as if scrapped across the sky on “Sunday Bloody Sunday” suggesting the turmoil of the lyrics, and after Bono’s command “LET’S GO!”, its staccato melody ties the song together; elsewhere, a rallying horn brings out “Red Light.”

#67. Slayer - Reign in Blood (1986)

Drummer Dave Lombardo: “I think [Rick Rubin] maybe made us a little more accessible to some people to where maybe those people wouldn’t have given it a chance otherwise.” That’s me being called out! I listened to this because of its reputation, sure, but mostly because, coming from a rap background, I wanted to see what Rick Rubin could bring to the table for a metal band. A lot, it turns out. What he does here is akin to what he would do for hip-hop around this time and even Johnny Cash later on: stripping it down to its bare essentials. Rubin removes any reverb, letting the speed of these songs hit harder. Quoting Rubin: “With their super-fast articulation in a big room, the whole thing just turns into a blur so you don’t get that crystal clarity. So much of what Slayer was about was this precision machinery.”

If Metallica was essentially louder and faster progressive rock, then consider this louder and faster hardcore punk—probably why I rank both of these bands the highest for metal—and tracks 2 through 9 remind me of Wire’s Pink Flag in how they get in and get out without wasting a second, and yet make room for introductions, verses, choruses, and even guitar solos such that the album clocks in at just under 29 minutes making it the second-shortest album on this list. Hooks too: “The only way out of here… … …PIECE BY PIECE!”; “JESUS SAVES!”; “I WILL BE REBORN!”; “EN…TER…TO…THE…REALM…OF…SATAN!” The lyrics within this album—contributing to its delayed release—are all pretty by-the-book metal controversial (the lyrics of “Altar of Sacrifice” was cited as the reason why three teenagers murdered Elyse Pahler in San Luis), but most of the time, utterly indecipherable except said hooks.

Slayer never reached this level of intensity again, despite continuing to link up with Rick Rubin. After whittling everything down to its absolute basics, there was nowhere else to go except to slow down, which is why 1988’s South of Heaven isn’t nearly as special.

#66. Éliane Radigue - Jetsun Mila (1987)

French drone composer Éliane Radigue got her start late. Born in 1932, she wouldn’t start composing her own pieces until the very-late 60s, after she was already a 35-year old wife and mother. While apprenticing with musique concrète inventors Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry at the Studio d’Essai, she learned composition but had no interest in their technique. Henry gave her some recording tech, and ten years later, she began composing her earliest feedback works quietly and late at night so as to not wake her children. Influenced by the American minimalists—which she sometimes gets compared to, even though she’s only comparable to one of them and certainly not the others—she ditched feedback for the synthesizer, and would eventually claim the ARP 2500 synthesizer as her instrument and no one else’s, which she used for 25 years to explore pure sound, and then promptly switched to composing for acoustic instruments in her late period. She became a Tibetan Buddhist in 1975, and her practice informed the deep spirituality of many of her works: composed in 1986, Jetsun Mila is one such example, inspired by the 11th century Tibetan yogi and poet Jetsun Milarepa.

If you’re curious about Radigue’s drone music, and want to sample it by jumping ahead on any given piece, you’ll notice that the pitch of the drone can change rather dramatically, but listening to it develop over the course of 45 minutes, as was her average, and that change is far more imperceptible. But there is change, an invitation to slow down in this fast life and observe them.

Jetsun Mila is one single work that runs 84 minutes, and the increased length allows her to explore the nine great periods of the life of Milarepa (plus a prelude), but she doesn’t bother making it easy for listeners by separating the piece into sections. But near the end of Jetsun Mila, there is a very slow climb as her synthesizer explores higher and higher pitch that aligns with “La réalisation (The Achievement)” before she dials it back down to represent “La mort (Death).”

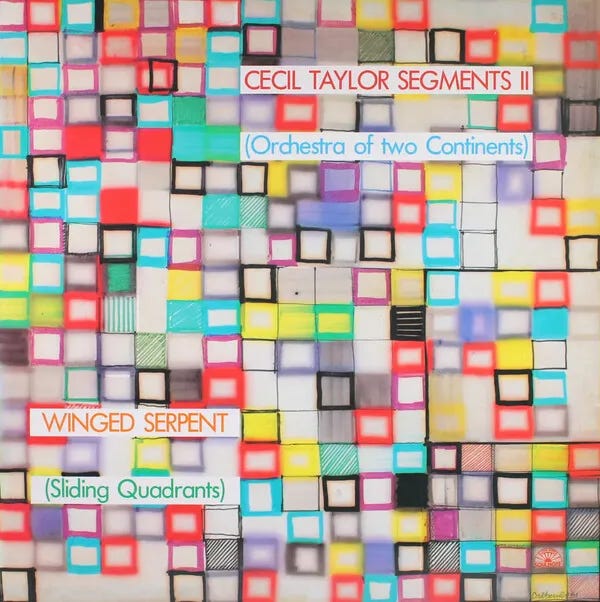

#65. Cecil Taylor - Winged Serpent (Sliding Quadrants) (1985)

The undecet—that’s eleven musicians—that Cecil Taylor assembles here includes some real heavy-hitters, including Polish legend Tomasz Stańko (trumpet), Dannish Ascension player John Tchicai (tenor saxophone), and free jazz legend William Parker (bass). But despite that, and despite the fact that the colour palette and squares of the cover clearly harken back to his classic album Unit Structures, and despite Cecil Taylor being one of the most acclaimed names in free jazz, Winged Serpent (Sliding Quadrants) doesn’t get nearly enough attention.

Cecil Taylor’s style as both pianist and composer—which is what he’s credited under here—is easy to describe: he wanted to see how much sound he could cram inside a pre-defined space. Walls weren’t walls to him, they were just hurdles to leap over. It’s no surprise to learn that his music training included learning to play both piano and drums, because he approaches the piano in a very percussive manner—he has even referred to piano keys as 88 drums—taking the tone clusters from the modern classical composers like Béla Bartók and Leo Ornstein and putting them to use in a jazz context.

What makes Winged Serpent (Sliding Quadrants) extra special is that his attack is coupled with the onslaught of 10 other musicians, and the results are overwhelming-by-design but with enough room that you can hear each element clearly. Gary Giddins made the point in Visions of Jazz that “Taylor has shown a tantalizing talent for voicing saxophones; all he’s ever needed is two to get a firm, woodsy, consistent sonority that sounds like nothing else in or out of jazz,” so what do you suppose happens when Taylor gets his hands on five reeds? Nothing short of magic. As are the drunken sway of the trumpets on opener “Taht” when the chaos clears away to only reveal more chaos.

#64. Big Black - Atomizer (1986)

Big Black are the rarest of rock bands in the 1980s, and their short and basically-perfect discography represents a possible avenue for hardcore: they got even louder and noisier and, well, more hardcore while everyone else around them grew up. What made them particularly special is the drum machines. Unlike other bands that were using drum machines pretending to be humans (or worse, using a human drummer pretending to be a drum machine), Steve Albini leveraged the Roland drum machine as an unstoppable monolith. (Michael Azerrad: “Thanks to Roland the drum machine, as the band soon dubbed their silicon-hearted fourth member, their groove, normally the most human aspect of a rock band, became its most inhuman; it only made them sound more insidious, its relentlessness downright tyrannical.”)

“Kerosene,” which runs for 6 minutes functions as the album’s climax, its centerpiece, and it’s also one of the greatest rock songs ever. The guitar clangs like glass being shattered and then scraped around. Pezzati’s bass adds to the intensity, a one-note-per-measure drone that serves only to intensify the drum machine’s rhythm. The song itself is a harrowing depiction of small town life, I’d argue even more scary than Suicide’s depiction of a capitalist worker at the end of his rope on “Frankie Teardrop.” The narrator admits to a boring existence (“Never anything to do in this town”) but also that he’s probably going to die there, and so his solution is sex (“Kerosene around, she’s something to do”) and self-immolation (“Kerosene around, set me on fire”), and it feels like looking into the brain of someone about to do something terrible. And unlike “Frankie Teardrop” which frankly doesn’t reward multiple listens, “Kerosene” simply sounds magnifique even before Albini opens his mouth: its reward is the noise, not the fright, which is the other way around for that Suicide song. The rest of the album doesn’t reach “Kerosene”’s high—“Jordan Minnesota” comes close with its riff but the ending is gratuitous and Albini regrets the song anyway—but they often do the same thing of presenting very heavy noise to backdrop short story lyrics about frankly terrifyingly real people (which is part of why Albini regrets “Jordan Minnesota”: the news story that inspired it turned out to be fake). True, an older version of Albini would have been able to go further in depicting the corrupt cop on “Big Money” (he barely has anything to say about them here), but the crook is just part of Albini’s version of small town America which is full of sex addicts (“Bad Houses”), alcoholics (“Stinking Drunk”) and war veterans unable to adjust to normal life (“Bakooza Joe”).

We all know what happened next: Steve Albini became the most unlikely of rock producer-auteurs. What I like most about Albini, aside from making the Pixies sound like they were playing in a surreal BDSM dungeon on Surfer Rosa and aside from his hilarious tweets about Steely Dan, is that he made a point about helping anyone who asked which is how he ended up absolutely everywhere: from penniless indie bands to Japanese post-rock Mono to Chinese Wire-lovers P.K. 14, from Robbie Fulks to Joanna Newsom, and everything in between.

#63. The Police - Zenyattà Mondatta (1980)

What made the Police great was that the band was composed of three musicians that played in telepathic lock-step and a virtuosic technique more readily associated with jazz than new wave, a genre where frankly great musicianship was rare, besides them and Talking Heads. (Indeed, bassist-front-man Sting once moonlighted for a jazz band, and would eventually feature on a Miles Davis album, even if it was a bad one.) Their albums have obvious bits of filler on them—Outlandos d’Amour: “Be My Girl - Sally”; Ghost in the Machine: “One World”; Synchronicity: “Mother”—and a notable drop in quality from the first to second sides (or reversed on Synchronicity), but neither of those statements is true of their album Zenyattà Mondatta: it’s their tightest album.

Even the songs that guitarist Andy Summers—which are typically the worst songs for each album—and drummer Stewart Copeland turn in aren’t so easily criticized. Summers’ “Behind My Camel” is the second-best thing he ever wrote for the Police after “Omegaman.” Naturally, the band hated it, with Sting flat-out refusing to play on it leaving Summers to do the bass parts on his own, but Summers would be vindicated when it won the Grammy for the Best Rock Instrumental Performance. Elsewhere, Copeland’s “Bombs Away” has silly AABB rhymes—and a hook that’s too easy—but he still manages to write a clever line or two despite that (“The President looks in the mirror and speaks / His shirts are clean but his country reeks”), and Summers’ solo is incredible (so interesting the Summers would be so good to Copeland, but Copeland felt guilty and that’s the only reason why he leant a had on “Camel”).

The short “Canary in a Coalmine” feels like it should be filler, especially considering when it swoops in, but it’s actually a fleetfooted highlight thanks to Summers’ guitarwork and the irresistible melody (it’s my favourite song here). The oft-mocked “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da” is an interesting and successful thought experiment to prove out how lyrics are the easiest thing to criticize about a music (that, and album covers), and that’s what people resort to because they don’t have the education to talk about melody — which the song has in spades. Meanwhile, “Don’t Stand So Close To Me” tests out adding synthesizers—the swelling at the start, and Summers’ guitar synth wash near the end—to their classic reggae sound and yield the album’s biggest hit, but unlike the synthy songs of their next two albums, it’s still very much the Police instead of Sting and synths. Follow-up Ghost in the Machine leans harder into atmosphere—especially on political single “Invisible Sun”—but the increased role of keyboards (every member plays some) makes it feel very much like an 80s album that Zenyattà Mondatta doesn’t.

#62. Horace Andy - Dance Hall Style

Like most people my generation, I came to Horace Andy’s solo work by backtracking from Massive Attack; he’s the only person that’s features on all of their albums, and he’s got quite the pull with them: “Angel”—arguably both his and Massive Attack’s highlight—was famously redone on the spot when he said he would not, because of his religion, sing the original cover which was Clash’s “Straight to Hell.” Dance Hall Style stands out among the handful of Horace Andy records I’ve heard because of Lloyd “Bullwackie” Barnes’s production. Look up any good dub record from 1982 and chances are Bullwackie was behind it (including Junior Delahaye’s Showcase and Wayne Jarrett’s Showcase Vol 1; the latter of which contains the second-best dub song I know): Bullwackie was easily Producer of the Year for 1982, and that’s not up for debate. What makes this record better than those is Horace Andy’s voice: buttery smooth, soulful, and with an unmistakable vibrato. This is dark, reverberating, and cool, and it’s one of the most obvious reference points for trip-hop. Ultimately, Andy and Massive Attack were such a match made in heaven precisely because Andy had already mastered singing over dark beats a decade prior.

Andy reworks some songs from his catalogue, and in both cases of “Cuss Cuss” and “Money Money,” improves on them. Barnes’ touches on the former makes it seem like the entire band is playing underwater, while a darker beat suits a song whose lyric is “Money the root of all evil” compared to the punchier version on Showcase, and the way sounds are drenched in reverb and layered together (around the 4:18 mark) is a trick that he’ll bring with him on “Angel” to Massive Attack. On that note, there’s also “Spying Glass,” where Andy describes voyeuristic neighbours to governments (purposefully left ambiguous), which some may recognize for appearing on Massive Attack’s Protection. If you’re someone with more technical know-how than me, please skip to the 2:11 mark and nab that drumbeat for the climax of a bad-ass hip-hop song, I’m picturing something that doesn’t even contain drums up until that point.

All told, this is the most immersive dub album I know—more than any Scientist album, that’s for sure—and every cut has at least a sound effect that’s worth seeking out, such as the guitar flickers 3 minutes into “Let’s Live in Love” or Junior Delahaye’s drums getting heavier on “Stop the Fuss” or Owen Stewart’s shimmering organ on “Lonely Woman.” Alas, from what little I've heard, Horace Andy hasn't returned to this murky style until Massive Attack, having switched from dub to incorporating the digital dancehall style that had become prominent.

#61. Dolly Mixture - Demonstration Tapes

Dolly Mixture are a trio consisting of bassist-vocalist Debsey Wykes, guitarist-vocalist Rachel Bor, and drummer Hester Smith. Their very small discography—only one album, this one, and some extras that was all compiled on 2010’s Everything and More—is very special: early-60s’ girl group, but with more guitars in the mix befitting the early-80s’ new wave. This particular album of demo-quality recordings contains 27 songs, most of them short, and so is plays like—take your pick—a twee pop take on Wire’s Pink Flag, or a female-led version of the Magnetic Fields’ 69 Love Songs. or a more competent version of Beat Happening’s debut. (That said, incompetence was the charm of Beat Happening, and I would have included it on this list had the 2004 reissue been released in the 80s.)

The first handful of songs are loaded with hooks, not just in those songs’ choruses, but their introductions, verses, and bridges too. “My mother told me you should stay home”; “Are you lying in the gutter / Does it even seem to matter?”; “How come you’re such a hit with the boys, Jane?”; “She’s ready to go (OH!)”; “You’re not the biggest catfish in the sea.” They’re clearly very interested in girl group: “Miss Candy Twist” could’ve been the title of a Marvelettes’ song, while the bridge of “How Come You’re Such a Hit With the Boys, Jane” plays like a Shangri-Las song. Elsewhere, they test out orchestral touches a la Phil Spector for the Shirelles on “Whistling in the Dark,” with strings and woodwinds.

Sure, these are demos, and there are some cases where I wish they got a proper producer to workshop the tracks into proper songs: when the guitar riff thickens on “Jane,” I want to blast that shit all the way up! But overall, the rhythm section still works up quite a bit of muscle in places, including the tumble of “Angel Treads” or the drum-rolls of “Winter Seems Fine,” while Rachel Bor gets in plenty of sugary guitar rushes. Famously, the Angels’ “My Boyfriend’s Back” was a just a demo, and that ended up being one of the best songs of its genre, so I don’t see why Dolly Mixture needed to spruce up these songs any more than they have. The best girl group album since the 60s!

![My Neighbor Totoro [1920×1080] : r/wallpaper My Neighbor Totoro [1920×1080] : r/wallpaper](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!iTzF!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8a61ddac-7d75-4e30-adad-55379226d7a4_1920x1080.png)

![Cover art for ただいま。 by 矢野顕子 [Akiko Yano] Cover art for ただいま。 by 矢野顕子 [Akiko Yano]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!oTdz!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa8ced2d8-86b9-44e2-94ba-bad854cc08b6_600x611.webp)

![Cover art for Wave Notation 1: Music for Nine Post Cards by 吉村弘 [Hiroshi Yoshimura] Cover art for Wave Notation 1: Music for Nine Post Cards by 吉村弘 [Hiroshi Yoshimura]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Onu5!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7e6e738c-4236-499f-835e-bbdc09c52fc4_600x602.webp)

A good few personal faves among this selection, too (Winged Serpentv, Chomp, Bad Brains, Atomizer, Swordfish). Looking forward to what’s to come.

Tortuous date for this to come out - my dissertation is due tomorrow and my real instinct is to read all this instead. A treat for handing-in tomorrow? Still exciting to watch picks slide *down* from the old one, hinting at more to come, and seeing some great stuff filter in as well: pleased to see Tadaima! I assume you've found translated lyrics for the medley, but if you haven't it's very charming stuff. Yr assertion re: HR innovating where rappers haven't is the kind of assertion that I might find the most amazing part of your writing - astute (and funny!) comparison across genre and scene is a skill that seems like it should be more prevalent in the digital world, but it isn't. That Pylon track 'Crazy' has been one of my favourites ever since high school - those deadpan-laugh backing vocals, the droning "the sun...", the split-personality twin chorus lines, the weaving golden guitar line; the fish on the single cover. Agree that Stipe couldn't put across the necessary energy (even though I love that REM tried!) and that Gang of Four, who are at least fascinating for so thoroughly interrogating and refashioning a rock band, never made music as cool and fun as this. Weirdly enough, I might even prefer Gyrate to Chomp!