Wire

Adapt to change, stay unimpressed

The feeling I get from Wire is that they’re too smart for their own good. The tag that has always followed them is their art backgrounds: Gilbert was an abstract painter, bassist Graham Lewis was a fashion designer, and vocalist Colin Newman was studying illustration before Wire; only drummer Robert Gotobed didn’t come from a visual art education, so no surprise that he was the first to leave the band when he got fed up with the band’s experimentation. Their visual art degrees came in handy for their cover art designs, particularly the striking central focus of the images on their first two albums.

No surprise they didn’t stay with punk for long: they were never punks to begin with. For one thing, guitarist Bruce Gilbert was notably much older than the norm; born in 1946, that makes him 31-years old when they recorded Pink Flag, and so he approached punk guitar with a different mentality than his younger peers close to half his age. They expanded their influences into avant-garde rock from Captain Beefheart, Neu!, and Roxy Music, and switched over to icy-detached art rock practically overnight.

And at their height of their popularity—they were never that popular, but 154 hit #39 on UK albums chart—they shot themselves in the foot over and over again, severing links to EMI and any potential future labels; upset by both alleged tampering of the charts from EMI to artificially boost “Outdoor Miner” up the charts and annoyed that EMI didn’t think there was value in promoting music through videos. They disbanded and re-emerged, but without kowtowing to anyone’s expectations and flat out refusing to play anything prior to their reformation. Decades before the MF DOOM imposter fiasco, Wire did something similar, enlisting a band called the Ex-Lion Tamers to open and cover their “hits” so they could do whatever they wanted for their actual set. They changed their sound, lost a member, changed their name, went on hiatus, reformed again, lost another member. To be a Wire fan is to be a frustrated fan for any number of reasons.

To add to this is that their album titles and song lyrics are often in-jokes between band-members, or simply puzzles for their audience members to work out themselves. For example, “Ex-Lion Tamer” was famously originally intended as “Lion Tamer,” but after serious edits, the band rebranded it “Ex-Lion Tamer”; 154 was titled because they had played that many concerts at that point; Object 47 because there was that many “objects” in their discography; a live song named “Eels Sang Lino” is an anagram of “Los Angeles” which got lost in the mix when they named it “Eels Sang” for the studio version. All this to say, I get nothing out of Wire’s lyrics, often described positively as “abstract” — I prefer “meaningless.” So when I see Graham Lewis making a big deal about “1 2 X U”’s lyrics, “which is about queerness and it’s transgender-based, not that anybody noticed,” I can’t help but want to respond, maybe no one noticed because there’s not enough lyrical substance to say the song is about anything: the majority of the song is the line “I saw you in a mag, kissing a man” repeated. The result is that I often leave a Wire song feeling the exact same as I went in, which is assuredly not something that happens when I listen to Talking Heads or the Fall, where there’s just more depth — and groove too.

For me, personally, I wish they made just one more record in spirit of Pink Flag because I think it’s their best by a very wide margin, and as good as their next two albums are, I can never help but wonder what would have happened if Brian Eno saw Wire when he visited London instead of Talking Heads. I doubt Wire ever had a Remain in Light in them, but I’m sure Eno—whom Colin Newman had met because they shared the same car when Eno was hanging around Watford—would only have helped shape some of their cold and detached soundscapes into better songs, while Talking Heads would have remained a tight live unit without Eno. Actually, it’s likely Talking Heads would have been even tighter since Eno’s friendship with David Byrne eventually caused a rift between Byrne and the other members. Essentially, by changing history a little bit, I think you’d end up with a slightly worse Talking Heads discography and a vastly improved Wire discography.

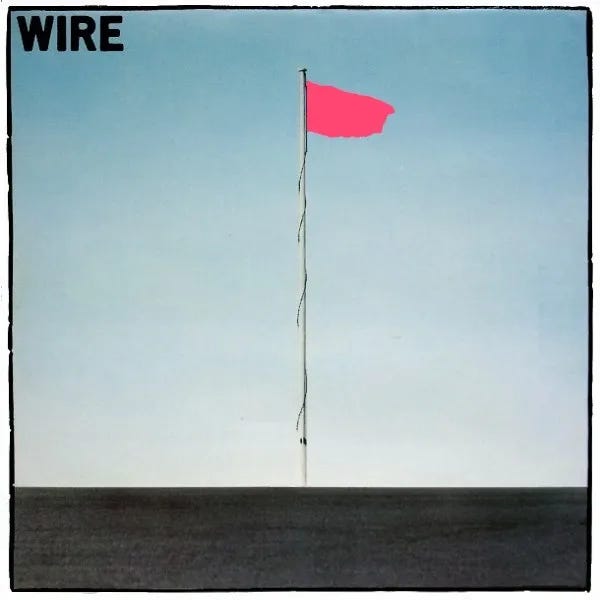

Punk rock was minimalism at its core, shedding off the excess and decadence that had permeated into rock music, but Wire stripped down even more on Pink Flag. 21 songs in less than 36 minutes, made possibly by having every song get in and get out without worrying about guitar solos—they ditched their original lead guitarist George Gill after realizing their sound was better without him—and often without bothering to parse out songs into traditional verses and choruses. And yet, somehow, I think it’s catchier than any punk record of those nascent punk years with the exception of the Ramones who were far more pop anyway. “Go under, go under!” and “There’s great danger (danger)!” and “1 2 X U” (cheeky self-censorship that also doubles as a count-down and sounds like “Want to X you”) are hooks that I’ll carry with me for the rest of my life, to say nothing of the playful way Colin Newman sings “The impossible…” on “Three Girl Rhumba” (which only happens once) or the British Invasion vocals of “Mannequin” or the handclaps that lead “Champs” out. “Field Day for the Sundays” accomplishes more in 28 seconds than most bands could hope to in 3 minutes, and “Reuters” is a case of a punk band discovering post-punk by accident. True, I’ve heard the album many times and couldn’t match titles to songs if you paid me: such is life when you’re dealing with short songs like these; I wouldn’t know “Brazil” at all if it weren’t for the “split the atom” bit.

Not only was “Strange” picked up by R.E.M. into a heartland rocker and “Three Girl Rhumba” was lifted into an Elastica hit (and had to be settled out of court), but the album would have a profound effect on hardcore scene. In particular, Minutemen took Pink Flag’s short and radical song structures to heart (Mike Watt: “It was like that NYC band Richard Hell and the Voidoids without the studio gimmickry, but Wire was way more ‘econo’ with the instrumentation and the radical approach to song structure […] They were big-time liberating on us”), while Minor Threat, Bad Brains and Henry Rollins have all covered songs from this album.

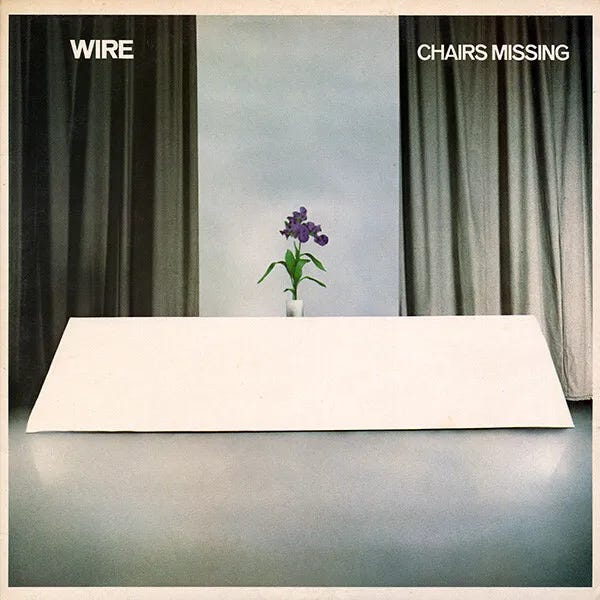

There is no song on Pink Flag that breaches the 4-minute mark, and the first song on their second album Chairs Missing proudly announces the radical departure: it’s an over 4-minute song that barely reaches a simmer, whereas all 21 of Pink Flag’s songs boil all-the-way through. Producer Mike Thorne plays an increased role by adding synthesizers, which the band take great care to treat in such a way that they sound closer to guitars, and tinker their actual guitars to make them sound closer to synthesizers. “Another the Letter” feels like Another Green World by way of Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), while “I Am the Fly” feels very much like an XTC pastiche with its ridiculously-chanted chorus (that I’d rather listen to over most XTC), and the guitar bridge actually does make me think of the tinny buzz of a fly’s wings. “Outdoor Miner” is them flexing their tune-craft, and the single would have got Wire to appear on Top of the Pops until the British Market Research Bureau alleged that EMI was rigging the pop charts by having label personnel buying multiple copies, which caused the song to plummet out of the charts. Not everything works: “Heartbeat” is a build-up in search of a song (with apparently some flute); “I Feel Mysterious Today” has some cool percussion textures from Gotobed, but the song is content to lean on its foghorn blasts like one of Hans Zimmer’s lazier soundtracks.

In an alternate universe where they did perform on Top of the Pops, maybe they would have written more songs like “Map Ref. 41°N 93°W” for their next one, because it’s forever disappointing to me that nothing on 154 sounds remotely similar. That song is the closest thing Wire ever made to great pop song, so of course they made the song title map coordinates instead of something easy to remember (Centerville, Iowa); the groove isn’t punk chug like their previous two records, but rather something you could actually move your body to. “Two People in a Room” is something I wish they wrote more of, which is the thrust of Pink Flag but from the vantage point of being an art rock band; the last minute or so of “The 15th” is a pure exploration of guitar-synth textures that I could imagine Eno-era Roxy Music doing. On the flip side, I find it generally disappointing that the record as a whole continues where Chairs Missing left off without improving at all in any way. In fact, “A Mutual Friend” bores when it enters its quiet chamber sections, and “Blessed State” is a clear attempt at making a Neu! song without the elements really make Neu! special. As an art rock trilogy from 1977-1979, I ultimately have to rank Wire’s lower than Talking Head’s first three albums (two with Eno) or the Berlin Trilogy from David Bowie (also with Eno).

Rather than promote their new single and help coax it into the charts, Wire decided instead to launch a 4-night stay at the Jeanette Cochrane Theatre in London called People in a Room with each member doing a solo performance culminating in the full band finally getting on stage and performing very little from 154. People in a Room pissed off EMI, although the hostility went both ways: the band wanted to promote their music with music videos before that was the norm, which the label didn’t see the point of back then. At London’s Electric Ballroom on February 1980, captured on the live album Document and Eyewitness released after they disbanded, rather than please any potential label people in the audience, the band went for all-out art terrorism. People expecting “the hits” got instead, an inflatable jet and an illuminated goose; they practically announce as much, teasing “1 2 X U” just to play a fragment of it. All Pitchfork’s Jason Heller tells it succinctly: “You had to be there—but most weren’t, and therein lies the eternal problem with Document and Eyewitness. […] The sound is unsteady and splotchy, and the band, always keen on deconstructing itself, has clearly taken that ethic to its inevitable dead end.”

The band regrouped in 1985, calling themselves a “beat combo” as one of their little jokes since they’ve never been interested in beat music (“I didn’t like rock & roll music – to me it was kind of old fifties music,” Newman once said to Rolling Stone). The problem with their music from here on out is that none of their producers are able to get as much from the music as did Mike Thorne.

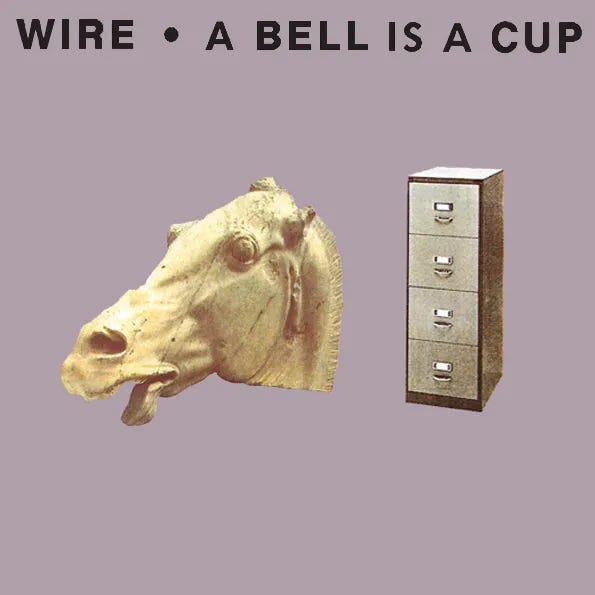

For example, they tap Gareth Jones for The Ideal Copy who had been producing for Depeche Mode and Einstürzende Neubauten which makes sense since the record is full of synth pop with even some industrial undertones (“Cheeking Tongues”). But Jones doesn’t let the synths shine, and so the New Order pastiches—the first three songs especially track New Order reverse-chronologically from 1986 back to 1983—just sound like copies and not ideal ones (low-hanging fruit there). A Bell Is a Cup... Until It Is Struck—brilliant title—is better thanks to two key highlights, “The Boiling Boy,” full of flutey synth textures that makes me think JRPG music, and “Kidney Bingos,” where they go closer for the pop jugular, but the album still doesn’t hold a candle to their early work.

They decided to get invested into remix culture next. It’s Beginning To and Back Again serves up live tracks from the band which were subsequently edited and remixed in studio, some improving on their studio counterparts (“It’s a Boy”) and others not (“The Boiling Boy”). They didn’t stop there either, releasing a full album of remixes of “Drill” from the Snakedrill EP. A lot of people consider The Drill to be their worst album, but I think it’s better than some of their 2010s output which is essentially the exact same thing: listening to the same song over and over. It’s also better than Manscape, the album that preceded it: 60 minutes with almost nothing to recommend it beyond some inspired hamming up on centerpiece “Torch It!” Feeling like he was being replaced by drum machines and loops, Gotobed left the band, and so the three-piece changed their name in solidarity to Wir (they joke that they were prepared to change to “Wi”—as in “We”—once another member left, and then “I” once it became just one remaining member). As Wir, they only released one album, The First Letter, a set of uninspired rock-techno hybrids.

Disappointingly, their foray with synths and remixes sucked away a lot of their raw power, so they came roaring back in the new millennium with Gotobed back on the kits on Send only to lose Bruce Gilbert right afterwards. Anything with Gilbert’s fingerprints on it was packaged up on the last Read & Burn EP (the first two were plucked through to make Send), and then they promptly worked on Object 47 to kick off their late period without Gilbert. How vital Gilbert’s guitar was to Wire’s sound is up to debate: Newman told Rock Cellar Magazine that Newman was the one that taught Gilbert how to play the parts on Pink Flag in the first place and then had to pick up a guitar himself later on because Gilbert couldn’t play certain parts, and so Gilbert’s absence doesn’t really affect the band’s sound. For example, you’d think they’d go back to their synthesizer era, but they decidedly don’t. The glam strut of “Are You Ready?” is flat-out awful, and the best song is the one where they try something different—closer “All Fours”—by having Helmet’s Page Hamilton bring in some “feedback storm.”

They were extremely productive once they added second guitarist Matthew Simms to their line-up, releasing five albums in the 2010s compared to only two the decade prior. There’s reverb applied to the vocals on Red Barked Tree which only removes a lot of the edge that’s native to them. The press release mentions that the album “rekindles a lyricism sometimes absent from Wire's previous work,” and I can see that Newman’s working harder on the words, it’s also not what I listen to Wire for. “Please Take” sounds like faceless Britpop to me with an f-bomb ooh-la-la. The title track—performed on a bouzouki—is worth checking out for something totally different from them, but Newman didn’t (could not?) produce it in a way to let the acoustic instruments shine.

Change Becomes Us is the very rare instance of this band looking backwards to their classic era, unearthing songs that were written for a fourth album that never came to be, or recording new versions of old songs from both their catalog (“Doubles & Trebles”) and Colin Newman’s solo career (“B/W Silence” and “Time Lock Fog”), and even “Eels Sang Lino” from Document and Eyewitness. The short songs all glimpse the band in their pre-1980 days, displaying sweat and speed that they’d never bother with again. And even then, it’s not as good as Parquet Courts’ Light Up Gold—their best album—which sounds very much like Pink Flag in its best parts.

“Blogging” from Wire has a quotable chorus (“Blogging like Jesus, tweet like a Pope / Site traffic heavy, I’m Youtubing hope”), but the self-titled album goes through the motions. Nocturnal Koreans was marketed defensively as a “mini-LP” to avoid scrutiny, eight songs leftover from the previous album’s sessions that Newman assures are different enough to warrant their own thing. It’s perhaps the only album of theirs in this period that didn’t arrive to at least some acclaim, but I strongly feel that “Internal Exile” is the only song of theirs post-2013 that I think fondly of because there’s actual thought to the texture—lap steel guitar, horns, and alien UFO synths—instead of just disaffected vocals singing non-melodies and blocky rhythms, which is exactly what Silver/Lead, Mind Hive and new set of reworked material 10:20 are full of.

Pink Flag - A Chairs Missing - A- 154 - B+ Document and Eyewitness - B- The Ideal Copy - B A Bell is a Cup... Until It is Struck - B It's Beginning To and Back Again - B Manscape - C The Drill - C+ The First Letter - B- Send - B Object 47 - B- Red Barked Tree - B- Change Becomes Us - B Wire - C+ Nocturnal Koreans - B- Silver/Lead - B- Mind Hive - B- 10:20 - B-