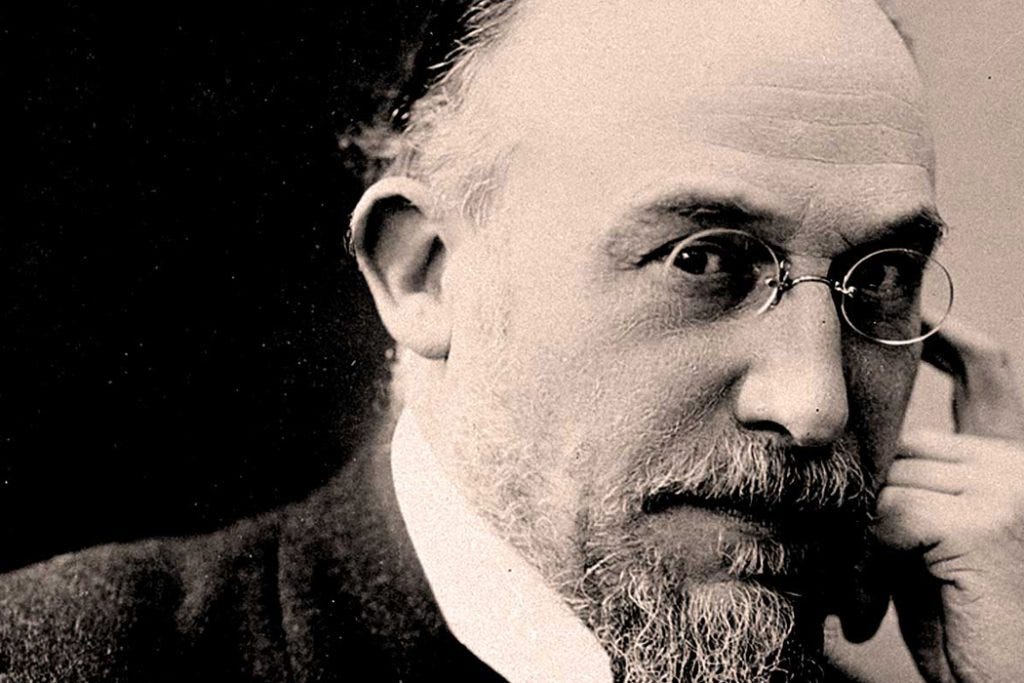

In classical music, there was no one stranger than Erik Satie. There are famous stories of the French impressionist stockpiling dozens of umbrellas or consuming 150 oysters in one sitting (rookie numbers), and he predicted Steve Jobs in that he wore the same gray, velvet suit every day for ten years in a row. His eccentric personality shone in his compositions, especially if you look at the written scores. Many were written in red ink, often without time signatures or bar lines, and with confusing instructions like “Be invisible for a moment” or “Open your head.”

Curiously, despite learning classical music through piano since I was 4 through the end of high school, I would never come across Erik Satie’s name until I got into popular music, where I found him practically everywhere: tributed by Japan and Aphex Twin, covered by Gary Numan, sampled by Janet Jackson, and name-dropped in basically every write-up on Brian Eno post-1975 by writers who traced a lineage between Erik Satie’s idea of furniture music—music meant for the background and not to listened to consciously—to Eno’s newly-coined ambient music.

What bothers me is that the last half-century has been spent reducing all of Erik Satie’s humour and innovations to these twin prongs of eccentricity and proto-ambient. The music that he labelled Musique d’ameublement, composed specifically to listen to as background music, was limited to only five pieces and yet people started applying it liberally to much of his music composed well before. I blame the slow-trickle of Satie-filled playlists marketed for the express purposes to help university students to study to ever since Blood, Sweat and Tears covered his Gymnopédies on a Grammy award-winning album.

To that end, I assuredly do not recommend Reinbert De Leeuw’s 1995 disc Gnossiennes, Gymnopédies which performs Satie’s famous sets at a funereal pace and ends up deconstructing Satie’s lovely melodies while stomping away at the pedals (hey, turned down softly enough, you won’t notice I guess?). For a single disc collection, you can’t go wrong with Klara Kormendi’s Piano Works (Selection) which crams 36 pieces into one hour which allows her to go deeper than just the hits, but since Satie didn’t compose much anyway, you might as well get a larger compilation like Alexandre Tharaud’s Avant-dernières pensées, one of the few sets that bothers with Satie’s few songs with vocal and chamber pieces in addition to all the solo piano good stuff.

Worth stating somewhere is that as much as I like him, I don’t think he ranks in the top 5 of his country, or as high as other piano-based composers such as Chopin, Liszt, or his close friend and fellow French impressionist Claude Debussy. Debussy orchestrated two of the Gymnopédies set as a favour to boost Satie’s financial situation and ultimately proved that Satie’s harmonies sounded best on the piano, but the two had a falling out because Satie didn’t think Debussy appreciated his later works, and refused to go to Debussy’s funeral. French pianist and noted Satie performer Pascal Rogé claims that “[Satie] was more daring than Debussy and he pushed him […] If Debussy had stayed with the pattern of music he was writing, he would not be considered ‘the great Debussy.’” True that some of Debussy’s solo piano pieces have similar ideas of the haunting and strange harmonies as Satie’s, but Debussy went far deeper afterwards: “Brouillards” leverages close tones bleeding into one another in strange and peaceful polytonality that wasn’t explored by Satie, Boulez considered Prélude à l'après-midi d’un faune the start of modern classical and there’s nothing written by Satie that could compete with the same scale, and a lot of jazz pianists improvised to sound like Debussy.

What I personally adore Satie for is because he was anti-establishment to his core, hence why most of his sets have made-up names instead of your more traditional preludes or sonatas; there’s nothing stuffy, serious, or even “high art” about Satie’s classical music; in fact, it’s almost all “low art,” often heavily informed by folk music or with Satie taking great strides to be the most humourous composer after Haydn.

Here’s a very loose guide of the essentials:

Before he got a knack on his personal style, he composed two short dances, both rather rudimentary attempts at Chopin but there’s an innocence to them that would flat-out disappear from Satie’s music immediately afterwards. Valse-Ballet is one of his earliest pieces, so naturally he marked it “Op. 62,” demonstrating his humour early on. It’s a simple waltz that I didn’t think much of until I heard Bojan Gorišek’s unique take on it on Complete Piano Works Volume 1 where the Russian pianist really emphasizes the dynamic shifts to make it effectively pop. Fantaise-Valse from around the same time is better, with an absolute swirl of a melody and making it clear that Satie was actually invested in waltzes and that these were not just parodies.

In 1887, he composed his first major pieces in the Sarabandes, influenced by a dance originating from the Spanish colonies of central America in the mid-1500s although ultimately not exactly danceable, but ideas of foreign rhythms shine through on the Gnossiennes; the word’s etymology predates Satie and referred to a dance by Theseus when he bested the Minotaur. Even the first one—the best one—has a ba-dum, ba-dum rhythm to it. The fifth is the fastest, but composed in 1889—well before the first three—it doesn’t sound like it was meant to be in the full set, and a major hint is that it’s the only one of the six that was written with a time signature and bar lines. (The opening chord seems to poke its head in the middle of Claude Debussy’s Hommage à Haydn.) The removal of bar lines in his compositions, especially in the slower Gnossiennes and the Gymnopédies might have been just an odd quirk for Satie, but for me, it’s a visual representation of what he was going for: a feeling of absence lasting an eternity. The first Gymnopédie is one of those cases where an artist’s most-popular song really is their best. Gentle ghosts; the hum of sweet rain; the steam of freshly-made tea; the moon, arriving early in the evenings. The Ogives rounds out this period, an attempt at making the piano sound like a cathedral organ by Satie stacking up harmonies into massive chords. With the exception of two of the six Gnossienne, all of these pieces were composed in a period of extreme creativity between 1887 and 1890.

Vexations has the command to play it 840 times in a row with the advice “to prepare oneself beforehand, and in the deepest silence, by serious immobilities.” The piece was first printed almost 25 years after Satie’s death by none other than New York composer John Cage, who organized its first notable performance with an army of pianists including Velvet Underground man John Cale. It’s often celebrated as an early example of minimalism, but only if you think the music made by the minimalists doesn’t change — something which is provably untrue.

For actual innovations, consider Le piège de Méduse, the first-ever appearance of a prepared piano in classical music (no wonder Cage loved Satie), or Le Piccadilly, an early example of a European composer being interested in American ragtime, or Sonatine bureaucratique (“Bureaucratic Sonatina”), moving in parallel with Igor Stravinsky from modernity to neoclassicism, and the happiest song from his late period. I’m glad that Cage unearthed Vexations and started a tradition of some brave pianists who took it seriously, but I also wish we all took it a little less seriously now.

Written in 1912, Véritables préludes flasques (pour un chien) is the first of absurdly-titled piano suites—“True Flabby Preludes (For a Dog)”—and the first movement is piano fireworks that stands out because he was rarely that flashy. The third movement brings back his fascination with eerie dances, but with the dance element far more pronounced. Embryons desséchés are little odes to different crustaceans—more specifically their desiccated embryos—but the second piece sounds like an impressionistic take on Chopin (i.e. the heavier bits bear remarkable similarity to Debussy’s “Brouillards” written just before) while the third piece has what he labelled an “Obligatory cadenza” which just ends and ends and ends with a barrage of ridiculous chords to mock the grand, ultra-fortissimo finishes common in so much romanticism. Avant-dernières pensées (“Penultimate Thoughts”) is the last of his humouristic piano suites, and the first movement of the former is a Bach prelude as imagined by an insomniac.

You can tell by the title of Choses vues à droite et à gauche (sans lunettes) that it was written during this era, “Things seen to the right and to the left (without glasses),” broken out into three movements with compelling titles like “Hypocritical Chorale” and “Muscular Fantasy.” It’s the rare piece by Satie to be composed for violin and piano, and the violin parts in the first movement are an equal mix of eerie and graceful and remind me of Morton Feldman’s late-period violin and piano pieces, while the third movement makes clear that Satie knew the ins and outs of violin technique even though he barely ever wrote for the instrument. Best of all is that Satie wrote in the score, “Mes Chorals égalent ceux de Bach, avec cette différence qu’ils sont plus rares et moins prétentieux”—“My chorales are equal to those of Bach with this difference: they are rarer and less pretentious”—which reminds me of Glenn Gould, except funnier.

The Nocturnes were composed in 1919 and have a stark seriousness to them. Key is that Satie gave them a traditional name for once. Thus, not only did he start his composing career by writing waltzes in the spirit of Chopin, he basically ended his composing career by writing nocturnes and coming full circle. Possibly informed by the death of Debussy (even if they had a falling out), or near-imprisonment after the response to his 1917 ballet Parade with Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso, the nocturnes reject the humour of basically everything that preceded them that decade, with far more compositional rigor than his normal pieces — they’re generally more difficult to play. Like Schumann’s Geistervariationen (which are proto-Satie and underrated) or Schubert’s last sonatas, there’s a real finality that’s explored in these five pieces. He passed away in 1925 from cirrhosis of the liver caused by his heavy drinking, especially of absinthe.