I got a lot of derision for that tweet, and some people quipped that rather than hating or gatekeeping, I should be recommending jazz albums instead — as if I didn’t do that in the thread. But here’s a recommendation instead Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters: literally any other album Hancock made before it, because I count at least four albums better.

There’s a well-traveled story that, while recording Miles Davis’ Miles in the Sky, Hancock arrived in the studio to discover that there wasn’t a piano, and Davis invited him to the play the Fender Rhodes instead, igniting an almost total abandonment of acoustic instruments in favour of electric ones as jazz moved into its fusion phase.

The problem with jazz fusion is the dumbing down of the jazz element, which Davis proved didn’t need to be the case, and that is especially true of Herbie Hancock’s music from Head Hunters-onwards. Of all the best-in-class talent that Miles Davis assembled for the Second Great Quintet, Hancock is the best soloist of them all, and I’m sorry, it’s not close. Whether he was the most important member is a different story: they were all integral. But he was an astral wanderer with an arsenal that included impressionist-liquid brush-strokes, a nimble technique, and harmonically strange and colourful chords, and he also took on the challenge of navigating Wayne Shorter’s and Davis’ increasingly-abstract and challenging compositions in a way that I can’t imagine many pianists from that era being able to — certainly not, for example, Red Garland from Davis’ previous Quintet. Miles Davis considered Hancock the next step in jazz piano after Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk and he was right: Hancock was the best jazz pianist in those post-Monk years.

You don’t get that in Hancock’s music after 1973. You get a synth mad-man interested only in new technology and pressing buttons, prompting jazz writer Gary Giddins at his harshest to remark “If Hancock had gone to the great beyond in 1968, he would now be solemnly regarded as a jazz god” in Visions of Jazz. That book is my jazz bible, and I think it’s very telling that Giddins devoted each chapter into many a prominent jazz musician but notably didn’t include Hancock, one of the best-selling jazz musicians ever — and one of two jazz musicians to ever win the Grammy for Album of the Year.

What’s more is that Head Hunters is a supposed gateway album into jazz and/or funk but is actually an aesthetic dead-end, hence its inclusion in my tweet. Here’s how I know. On Herbie’s side, he would never release music that would be challenging ever again despite his background from a hard-bopist turned avant-gardist before he became a synth-head. Basically, he was surging forward in his own lane for over a decade thanks to a curiosity of groove and his tutelage under Miles Davis as part of the Second Great Quintet, and he promptly gave up trailblazing in 1973, except to test out vocoder or turntable solos a.k.a. who the fuck cares. On Head Hunters, he—to use his words in the reissue liner notes—“wanted to play something lighter,” got commercial attention on a level that he and his peers never received, and never looked back. On the audiences’ side, there’s nowhere to go from Head Hunters except more fusion: the funk itself is too passive to work up much of a sweat, and the improvisational chops on display from Hancock and Maupin could have been from a bunch of journeymen. You’re welcome to like the record. I like the record. But that it has maintained its reputation as Herbie Hancock’s signpost record is embarrassing when you consider everything he did before it.

Here’s the guide to his core studio discography to try to convince you:

I. Takin’ Off: The Blue Note Years

I liken Herbie Hancock’s first two albums to that of Joni Mitchell’s (an artist that Hancock would work closely with and tribute); far more traditional—in this case, mostly hard bop—than what they would be known for, and also underrated as a result. Both are great. Takin’ Off (the debut) has the better band thanks to Blue Note tapping both Freddie Hubbard and Dexter Gordon to help Hancock, but My Point of View (the sophomore) has the better drummer with Tony Williams replacing Billy Higgins. Higgins swings, sure, but that’s all he does; Williams does that and more — his performance on “King Cobra,” is beyond Higgins. Both albums lead off with a maddeningly catchy hard bop number, inspired by Horace Silver’s groove that he’d take to heart for the rest of his career. Personally, I think “Watermelon Man” is the lesser of the two. Hancock claims he wrote it in 15 minutes—inspired by the image of the watermelon man going through Chicago with an old horse carriage, hence the rhythm—and frankly, it shows; I’d rather listen to My Point of View opener “Blind Man, Blind Man.” But “Watermelon Man” was funky enough that it convinced Blue Note that this new talent of theirs didn’t just play piano, but he could write his own compositions too, so they rejected Hancock’s idea of submitting some standards to pad out his debut, hence all of them being his own songs. It also became a standard. Legend has it, at a live concert from Cuban percussionist Mongo Santamaría where no one was in the audience, it turned into a jam session where Donald Byrd urged Hancock to show Santamaría “Watermelon Man,” who asked to record a cover of it, and scoring a top 10 hit in 1963 (at #10), giving Hancock his first taste of success.

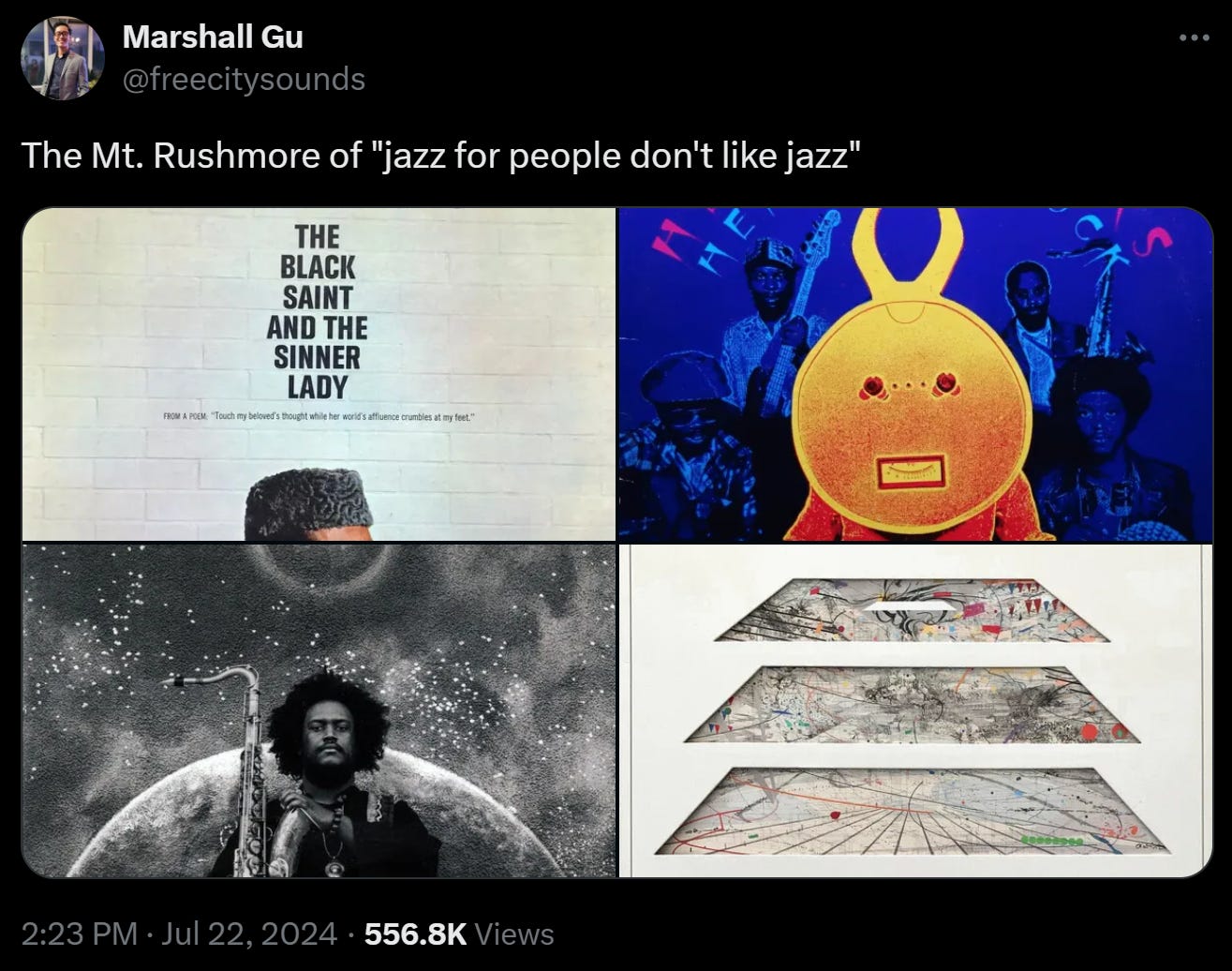

Seemingly bored already of the hard bop that made him a household name, Hancock shifted for the first time in his career on his third album Inventions & Dimensions. It’s his first outright masterpiece — and best album. “In December, 1962 and January, 1963, I worked with Eric Dolphy. It was my first exposure – as a participant- to ‘free’ music. mean, to a way of playing that allowed for more spontaneity than anything I’d been involved in before. At the beginning, I thought I’d be afraid to play just anything felt, but as I got used to it, the experience gassed me so much that I decided to plan for a record session in that vein,” Hancock explains in the liner notes. Miles Davis put the idea in Hancock’s head to use two percussionists, so Inventions & Dimensions sees Hancock with a unique team: percussionists Willie Bobo and Osvaldo ‘Chihuahua’ Martinez, and bassist Paul Chambers. Hancock only gave the players loose directions to work with, such as knowing the 6/8 time signature of “Succotash,” and only “Mimosa” had a tune worked out prior. The results are freer soloing than ever from Hancock: some of the chords on “Succotash” have an alien synthetic tone colour to them without needing to resort to an electronic instrument to produce them; “Jack Rabbit” proves his ability to improvise at breakneck tempo, and his soloing on “Mimosa” is gorgeous and inventive melody-making. “Triangle” is named because it has three parts, starting off with the most traditional 4/4 bop music on the album, and then entering a 12/8 Latin-jazz groove, and then returning to jazz. And yet, the album just misses the mark of ‘A+’ because I can’t help but know that a different bandleader like Davis or Dolphy would have pushed this rhythm section to be freer: Chambers plays ‘within the lines’ in such a way that I wish Hancock got Carter instead, and Bobo’s percussion on “Jack Rabbit” (when he doesn’t handle the solo) and “Mimosa” often sounds like a loop awaiting instruction.

Recorded in 1963, Inventions & Dimensions was released the following year and was quickly followed by Empyrean Isles — his second-best album. Tony Williams is back, drumming up a dark storm here unlike his far more modest work on My Point of View, joined by Ron Carter and Freddie Hubbard — so it’s basically like the Miles Davis line-up without Shorter. The compositions feel less naked than ever before, enabling jaw-dropping improvisations and interplay between the soloists. “One Finger Snap” starts off with a cascade of different and blazing cornet melodies, and ends with a drum solo that’s simultaneous thunder and rain courtesy of Williams; if “One Finger Snap” is the journey to find the islands, then “Oliloqui Valley” and “Cantaloupe Island” is finally getting there and enjoying yourself; Carter’s solo from 5:37 - 6:31 on the former sees the bassist practically flaying his strings to make them more emotionally resonant. “Cantaloupe Island” refines the harp bop of “Watermelon Man” and “Blind Man, Blind Man” into Hancock’s grooviest little number yet. And “The Egg” is Hancock’s best experiment, a 20-minute journey that begins with an addicting back and forth between Hancock and Williams and then proceeds to venture through the cosmos with bending of instrumental colour so they don’t sound natural: Hubbard manipulates the cornet into sounding like a wind instrument; Hancock’s melody disintegrates completely; Williams bangs out a beat on what sounds like a coffee mug; and Carter grabs his bow.

Disappointingly, Maiden Voyage is the only album that Herbie Hancock released under his own name that sounds anything like the albums he made with Miles Davis as part of the Second Great Quintet. But with the same Quintet rhythm section in tow, he works with Freddie Hubbard again and George Coleman on sax, and creates his third-best album, a rumination of the ocean and all of its vastness and deepness. The title track proves that he could write a standard that wasn’t rooted in groove but soul; Williams and Carter form the hurricane mentioned in the second track, and Hubbard blows furiously against their wind (1:35 = elephants railing); “Survival of the Fittest” is “The Egg” in mini, and the last time he’d be interested write anything like that his career (the opening even sounds vaguely similar). Alas, Hancock’s “Little One” isn’t as special as the version cut with the Quintet.

Speak Like a Child arrived after an unprecedented break between albums because he was busy with Miles Davis. Keeping Ron Carter, he opts for Mickey Roker on drums instead of Tony Williams, creating an airier album, but also frankly a far less enticing one. The other instruments—flugelhorn, trombone, and flute—are only there for welcome harmonic texture, something, I wonder, if he picked up from his pal Wayne Shorter who had deployed trombones and flugelhorns on The All Seeing Eye. Bookending the album are songs he learned with Miles Davis (love his solo on “Riot,” a spiraling staircase, hopping back down two steps at a time, a little hopscotch, and then meeting your friends), and in between is a sort of suite about childhood, with “First Trip” written by Ron Carter in tribute to his son, and then ending waving goodbye to childhood on the ballad. Maybe that’s how Hancock felt at the time, with the cover of him kissing his then-fiancé right before he married her later that year.

A little known secret is that The Prisoner is the far better album but this seems like a take that hasn’t quite caught up to Hancock fans yet. Maybe because it seems like a transition: it’s the first time the electric piano appears in his solo discography, and that the album loses steam as it goes on. But it’s not a transition at all: the majority of the album is performed on acoustic, and no future Hancock album would sound like this. As his last venture for Blue Note before he moved to Warner Bros, he expands the band into a nine-piece: the same instruments as before (although different players) but with additional bass clarinets, bass trombones, and a flautist too, enabling Hancock to show off his arrangement chops far more than he was able to on Speak. That, and the additional soloists: Johnny Coles and Joe Henderson knock their solos out the park on the Martin Luther King, Jr. tribute that opens the album (with the bossa nova hint in its rhythm). Elsewhere, Buster Williams takes a cue from Charles Mingus’ book on “The Prisoner,” the bass-line thick and constantly framing the whirlwind action around it.

II. Early Fusion: The ‘Mwandishi’ Trilogy

If anyone thinks about Fat Albert Rotunda at all these days, it’s because in 2011, Havoc finally revealed that the sample of Mobb Deep’s “Shook Ones Pt. II” is three seconds of “Jessica,” the lone ballad from a forgotten album turned into one of the most menacing songs in rap history. Every song on this album is flawed in some way, and in general, you have to go in knowing that the juiced-up horns are because it was composed for television. But the questions just keep coming: Why the wet crunch of the bass on “Fat Mama?” Why the weak-ass percussion on “Tell Me a Bedtime Story?” Why is the scratch-guitar just flickering on “Oh! Oh! Here He Comes?” Why is the mix so cluttered on “Jessica?” All told, the funk here isn’t nearly funky enough, and the songs aren’t giving the members of the septet that Hancock assembles much space to much heavy-lifting, jazz-wise. An exception comes early on “Wiggle-Waggle,” where the septet line-up is bolstered by five more horns, two guitarists, a bassist and most notable of all, Bernard Purdie on drums (Aretha Franklin, Steely Dan, Gil Scott-Heron) who is putting in work, so much so that you end up missing his presence for the rest of the album.

In the year that followed, Herbie Hancock rebranded himself as ‘Mwandishi,’ Swahili for ‘Composer,’ inspired by the spirituality in John Coltrane’s music that was never in his own, as well as the avant-garde fusion that Miles Davis was making, and formed a new sextet comprised of Buster Williams (bass), Billy Hart (drums), Eddie Henderson (trumpet), Bennie Maupin (woodwinds) and Julian Priester (trombone). This new group would release Hancock’s experimental trilogy, the best set of fusion albums by anyone not named Miles Davis. (Though it should be noted that Warner Bros has packaged up Fat Albert Rotunda with the first two entries of this trilogy twice as Sextant was released by Columbia — but no one thinks of Fat Albert with these albums.)

Mwandishi is the most underrated of the trilogy, and I think it gets less attention because “You’ll Know When You Get There” is essentially a In a Silent Way rip straight down to Billy Hart’s metronomic drums in the middle taking a page out of what Tony Williams was doing on that album, as well as large swathes of “Wandering Spirit Song.” But “You’ll Know When You Get There” has a weird humidity to it that Silent Way didn’t, especially thanks to Buster Williams’ bass-line during Bennie Maupin’s solo. “Ostinato (Suite for Angela)” is funk that I wish Hancock made more of instead of what came later, set to a tricky 15/4 meter, Williams knows the score and helps guide Maupin’s locust-buzz bass clarinet while Eddie Henderson proves himself as the best soloist in the group with Hancock now more focused on technology.

Crossings is the worst of the trilogy. What distinguishes the album—and makes it ultimately feel like a product of its time—is the appearance of the Moog synthesizer, a notoriously tricky instrument that many rock bands essayed and got nothing out of, played here by newcomer Dr. Patrick Gleeson which never feels properly incorporated into the actual songs. Not helping is that Bennie Maupin handles two of the three compositions, and they don’t stack up to Hancock’s “Sleeping Giant,” with “Quasar” never getting off the ground. Like the name suggests, it takes a while for “Sleeping Giant” to wake up—starting with a long, multi-percussion introduction—but once it does, it has an obscenely funky bass-line.

Sextant is the best of the trilogy. But “Rain Dance” is secretly its worst song. Yes, it opens with an ear-catching waterdrop percussion that earns both the song title and album cover — a full minute so addicting that Digable Planets sampled it in full and didn’t touch it to open their own debut album. But that’s all “Rain Dance” has going for it, peaking with the ominous bass-line around the 1:20 mark, and the second half is a wasteland where Hancock dicks around with a synth vamp that doesn’t go anywhere. “Hidden Shadows”—is that 19/8 meter?—has a solo that proves that acoustic piano could still fit into these increasingly un-acoustic songs, while Maupin pulls out all stops, including a kazoo, to make “Hornets” earn its title.

III. Head Hunters

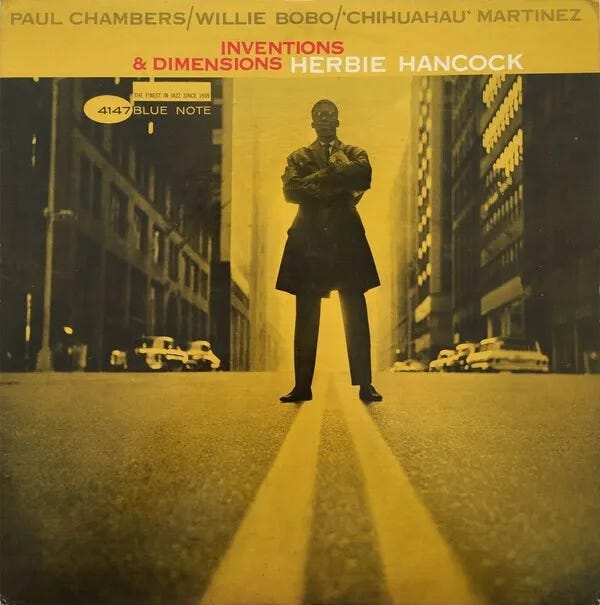

Head Hunters is an album of sound-bytes—the thick synthesized bass-line of “Chameleon”; Bill Summers hooky bottle-work of the “Watermelon Man” re-make; Bennie Maupin’s contributions in general—and so it makes sense that it was sampled so heavily in rap music from 2Pac, Digable Planets, and Black Milk, and that’s just off the top of my head. But it also wastes so much time! “Watermelon Man” is the shortest song here, and yet, it takes almost two full minutes to get going — things don’t kick into gear until Hancock lays down that summery chord at the 1:45 mark which Maupin responds to, and even then, it’s not like we’re off to the races; the song has actually peaked for me right there. Likewise, Hancock’s synths are set to ‘ZAP!” on “Chameleon” and I wish someone would have told him to tone it down a notch as he solos without saying anything for way too long. “Sly” (named after Sly Stone but it never makes me think of the musician or the music by the Family Stone at all) is the only song here that works up a sweat, and then “Vein Melter”—a metal title that deserved a far more scorching song—is air to me.

Some people prefer Thrust, and I’ll concede that the cover’s cooler and that Mike Clark is a better drummer than Marvey Mason, and Clark’s little cowbell sections on “Palm Grease” feel out of Mason’s reach. One point goes to “Butterfly,” a Maupin co-write with one of the best tunes to appear from now on going forward (no wonder Hancock would keep remaking it). Man-Child is when he incorporates lots of electric guitars—having tested them out previously on Fat Albert Rotunda—and goes straight for the funk jugular; “Hang Up Your Hang Ups” is a barn-stomper, and even though the bass-line of “Steppin’ In It” seems suspiciously similar to that of “Chameleon,” the solo is excellent, from none other than Stevie Wonder whose harmonica has an alien metal texture to it.

From here on, the jazz takes, not just a backseat to (because it had already done this), but it moves into the goddamn trunk to make room for the funk and disco, and though Hancock would still release some acoustic albums, like Eno and pop albums, this became more of a side hobby than his main pursuit. Secrets goes disco to inconsistent results (Kenneth Nash on the cuíca on “Spider” makes it a “late-career highlight” even though Hancock should only be in his mid-career here), and there’s a new reggae-fied take on “Canteloupe Island”—is there a reason this title is mis-spelt?—that’s vacuous, terrible and clearing chasing after the success of “Watermelon Man.” He tested the waters of digital vocals on “Doin’ It Right” which would lead to plenty (way too much) vocoder on the next three albums, Sunlight, DirectStep, and Feets, Don’t Fail Me Now, even scoring a British hit here or there (means nothing I’m afraid). There’s absolutely nothing wrong with a little catchy mall hook like “I Thought It Was You” but it just never ends; the Japanese-only DirectStep is a short one with just re-makes of recent songs, but peep it for Ray Obiedo’s solo on “Butterfly.”

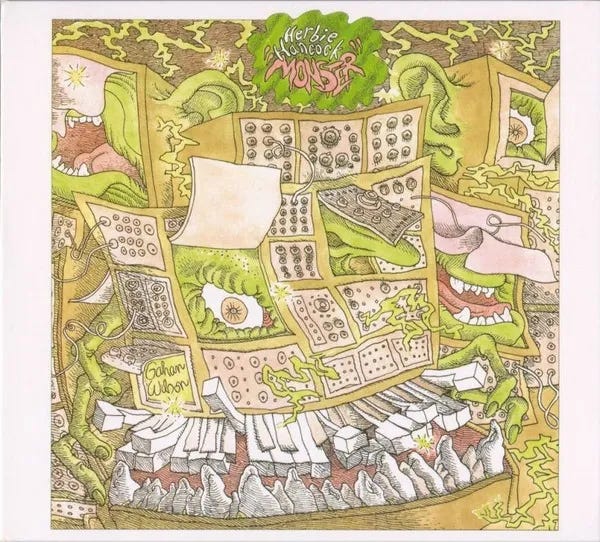

Monster has Hancock’s worst song at this point in “Making Love,” replete with lyrics like “When my body starts to rise / I can feel you synchronize” and “Riding at a gentle pace / Guide me to your special place.” Mr. Hands—a deeply unfortunate album title, don’t look it up, stop, go back—from the same year is a far better album. Skip the easy-going “Spiraling Prism” and head straight to “Calypso,” where Hancock teams up with Ron Carter and Tony Williams and then lament their loss as they never show up again here (there’s different people in almost every song for some reason); the steel drum solo from Sheila E. is silly and all good fun. Billy Hart goes nuts on “Shiftless Shuffle,” but better yet is the rightfully named “Textures,” a Hancock solo song with different instruments that’s a lovely piece of summer ambient. And then as quickly as he re-ignited his love for jazz, he disposed of it again on Magic Window and Lite Me Up (give the title track to a city pop master to make it really shine — but that’s actually exactly what happened two years prior and it was called “Silent Screamer” by Tatsuro Yamashita), neither particularly good.

I prefer the acoustic albums, but they feel fluffy. The Herbie Hancock Trio (recorded the same day as Third Plane with Ron Carter and Tony Williams; both are good albums although Carter is mixed way too loudly like he were Mingus; “A Slight Smile” should have been kept a Hancock solo effort, for example) and The Piano were Japan-only releases and not available in the States until much later because Japan was far more sympathetic to acoustic jazz while the States never recovered after fusion; these albums proved he could still rain starfire arpeggios or really get into a ballad, sure, but they’re also not as inventive as his older albums. One exception came in Quartet, where Hancock linked up again with his trusted rhythm section but added a young Wynton Marsalis, only 19 years old at the time of recording and playing to prove that he belongs with these giants, and the quartet smokes their way through Monk and Quintet standards, with the exception of the ironically titled “One Quick Sketch,” a total time sink. (I’ve covered other albums that Hancock was involved in in my write-up for Wayne Shorter and won’t bother repeating myself because they’re not worth the effort.)

IV. Electro and Beyond

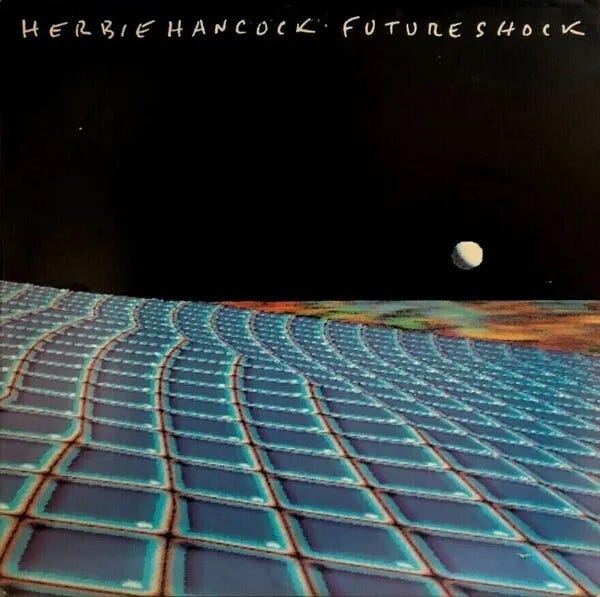

Having milked disco all that he could, Hancock tapped elements from an up and coming genre called hip-hop, working with producers Bill Laswell and Michael Beinhorn to reinvent himself for the first time in a decade. The results of Future Shock are electro, adding drum machines and turntables to his synthesizers, fitting for the year where the machines took over. “Rockit” became a surprise hit music video despite the fact that Columbia scoffed at the song and refused to give him budget; it hooks hard with that synth line, and it has the first-ever scratch solo on record courtesy of Grandmixer D.ST. The Curtis Mayfield remake goes on for way too long, alas, and some of the drum programming produces noises that are questionable (especially on “TFS” and “Earth Beat”), but the album is still the most vital that Hancock has sounded in a long time — which is kind of depressing to think about. He followed up immediately with Sound-System, more of the same but worse; “Hardrock” dares to wonder what electro would sound like with cock rock but doesn’t ponder the ethics of fusing the two. The best songs on that album are when Hancock teams up with Gambian multi-instrumentalist Foday Musa Suso, and so Hancock would hop on the world music train and release a full collaborative album Village Life afterwards which would be his best album of this period because it’s the Afrofuturism that he was so keen on exploring in the early 1970s reduced to its barest elements: his synthesizer and Suso’s kora. The only pox is the stunningly awful drum programming sound that Hancock chose for “Ndan Ndan Nyaria.” He ended the decade on Perfect Machine, the worst of his electro “trilogy,” with “Vibe Alive” usurping “Making Love” as the worst song in his career at this point.

He moved onto acid jazz on Dis is Da Drum, using housey breakbeats and bringing in a rap verse—because it worked so well for Miles Davis just before—on an album that’s never brave enough to ever be bad beyond the fact that it feels like it was made for yuppies. He covered the Beatles, Peter Gabriel, Stevie Wonder, and Nirvana on The New Standard, finally back to a talented and mostly all-acoustic band except for John Scofield’s electric guitar, and promptly moved to Gershwin, then back to electro, then pop collaborations. Some might call these “twists and turns.” I call it fishing.

He caught a salmon with River: The Joni Letters, but I’m sorry to inform you that it isn’t a real album. It doesn’t exist. Here’s how I know: no one has heard the whole album consciously. Certainly not the Grammy people who saw “tribute to Joni Mitchell” in the PR materials and threw the “Album of the Year” award at it — truly, one of the worst recipients of that award, which is saying something, especially because it’s an institution that has always ignored jazz (only one other jazz album has ever won the award before). Hancock’s coffeehouse renditions of Joni Mitchell’s songs make her seem like the most boring writer in the world instead of The Greatest Musician from Canada (or put it this way, they’re to her what her Mingus tribute album was to Mingus). Hancock and Shorter revisit “Nefertiti” from their old days, a song that Joni Mitchell has praised Shorter for, and it’s an album highlight on account that I don’t have to hear boring vocalists render Mitchell’s lyrics inert. I hit the skip button every time Norah Jones sings the title words of “Court and Spark” as boring as she does (whereas Mitchell sang it with such nostalgic rapture) or when Cohen goes “In a low-cut BLOUSE she brings the beer” on “The Jungle Line,” a song that was ripe for some Mooging and drum loops from Hancock to keep with the original’s weird vision but he plays acoustically. So I’m in that group of people that I talked about: I’ve never finished this album technically speaking.

Nor have I finished his next one, and also currently last studio album, The Imagine Project because, well, the first words on the track list are “Imagine (feat. P!nk).” In an interview with Mojo, Hancock explained that the motivation behind the record was “I decided to do something that addressed an issue of today. And the first thing that popped into my mind was the economic crisis,” and so naturally, he covered “Imagine” ten years before Gal Gadot. Collaborating again with great African musicians—Oumou Sangaré, recently-departed Toumani Diabaté, and Tinariwen—would have yielded far better results if Hancock didn’t stoop to covering sacred pop songs again and/or didn’t pair them with other guests that aren’t worthy of them, but Hancock sold his soul a long time ago.

Fuck the haters, Marshall!