(100 - 81 | 80-61 | 60-41 | 40-21)

#20. R.E.M. - Reckoning (1984)

R.E.M.’s sophomore album Reckoning was intended to be a water-thematic double album and I’m glad they ditched both fronts—although remnants about water remain: “Harborcoat”; “swallowing the ocean”; “rivers of suggestion”; “water tower’s watch”—because what’s left is an album with no narrative. It’s purely about music, which makes it harder to approach.

Murmur gets more attention because it arrived first, but Reckoning is a near-perfect collection of ten songs. Truly, about as perfect as it gets! And one of the differences between this and Murmur is that these are actually songs, with Stipe singing a lot more clearly from here on our, resulting in the clearly-belted hooks of “So. Central Rain” and “(Don’t Go Back To) Rockville.” You won’t need a lyric sheet to help you navigate other hooks, but that only leads to further ambiguities; for example, “Jefferson, I think we’re lost,” is an in-joke to manager-tour bus driver Jefferson Holt, sure, but it’s also a harrowing line about the very real political climate that R.E.M. no doubt felt at the time.

The increased focus on songs does yield some underwhelming cuts: “Time After Time (Ann-Elise)” has the hard task of following up the opening four songs, and it doesn’t deliver beyond the interplay between Buck and Bill Berry on bongos; “Camera” strikes for the emotional resonance of “Perfect Circle” but spends almost twice as long not achieving it (it’ll be the first song that I always outright skip on the R.E.M. catalog). But the other songs are impossibly great, with producer Mitch Easter adding a shimmer to Peter Buck’s guitar that makes these songs feel watery in contrast to Murmur’s earthy-atmospheric tone; Mike Mills’ backing vocals on “So. Central Rain” (at the 1:50 mark) feel like he’s falling out of a dream in slow-motion, while the pounding piano in the song’s climax represents Michael Stipe’s emotional, well, reckoning. Michael Stipe is the rare sort of singer that can sing you a line like “There’s a splinter in your eye that reads react” and then follow it up by spelling out the last word, and somehow extract meaning from it all. (I’ll be wearing a harborcoat in my shady lane as I’m living out my range life.) “(Don’t Go Back To) Rockville” is the saddest song from that decade not made by the Replacements because the big cities keep churning, and you keep churning in them, and friends and lovers will leave and they don’t come back. The conversation’s dimmed. The trees will bend. The cities wash away.

#19. The Replacements - Let It Be (1984)

I will never listen to this album front-to-end because there’s too many unsubstantial cuts—namely “Tommy Gets His Tonsils Out,” the cover of Kiss’ “Black Diamond,” “Gary’s Got a Boner,” and “Favorite Thing” had it not been for its climax (“You’re my favorite thing…you’re my favorite thing…BAR NOTHING!”)—and I think the record should have ended with “Sixteen Blue” because “Answering Machine” is another distressing emotional song that just isn’t able to plumb as deep as the previous song despite the power of its ending. But the people who think 10s only consist of songs that are perfect are the dumbest people to walk the earth—these people are all finance bros with Gladwell and Mark Manson on their bookshelves; prove me wrong here—and if you’re not getting some drunk toss-off, then you’re not getting the full Replacements experience. (Oh, and a quick word about the mostly-instrumental “Seen Your Video”: that riff kicks ass.)

Hidden within this punk-turned-power pop band was one of the greatest singer/songwriters of the decade in Paul Westerberg. Throughout Let It Be, Westerberg sings to you—yes, you, and me too!—as if he’s lived our lives. “How young are you? / How old am I? / Let’s count the rings / ‘round my eyes” are the first lines on the album and he makes clear that he feels much older than his years while Tommy Stinson lays down one of the best bass-lines in indie rock on “I Will Dare.” “Androgynous” comes out of nowhere, performed as if Westerberg’s playing alone on an out of tune piano that was stored in the attic for decades on a song that quietly takes its place in the LGBT canon started by Velvet Underground’s “Candy Says.” “He might be a father, but he sure ain’t a dad,” and “She’s happy with the way she looks / She’s happy with her gender” hit like bricks. And “Unsatisfied”—which begins with a crystal acoustic guitar introduction straight out of Big Star’s #1 Record—features an emotional outpouring that outdoes Kurt Cobain at the thing Cobain was best at. “I’m so! I’m so! Unsatisfied! I’m so! Dissatisfied!” You and me both, brother.

Someone I knew once messaged me, sad that he was turning 17 years old and would no longer be able to identify with “Sixteen Blue.” I’m turning 34 years old this year and I still identify with it. It’s not just Westerberg, whose able to muster enough strength into a growl in the face of total despair, “You don’t understand anything sexual / I don’t understand…”, but Bob Stinson’s guitar tone alone is enough to send me into a depression trip. Indie rock after the Replacements had become loaded with irony and then ironic detachment, so as defeatist as it might be to say “they don’t make ‘em like this anymore,” well, the Replacements were about defeatism so maybe it fits. Indie rock didn’t die: it just changed in ways that I don’t like. What did die, however, was its sincerity.

#18. Sonic Youth - Sister (1987)

The noise is more potent than ever on Sister, as are the moments of tenderness; running at 38 minutes—almost half the length of their next, more acclaimed album—it’s their tightest, most filler-free album. It’s almost perfect: “Pipeline/Kill Time” owes much to Steve Shelley; Crowns cover “Hot Wire My Heart” feels superfluous; “Beauty Lies in the Eye” doesn’t hold a candle to the preceding two songs, which are both among their very best.

“Tuff Gnarl” has Moore’s voice rising above the din of guitars to pair together words that you wouldn’t think should go together: “Amazing grazing, strange and raging / Flies are flaring…” to the point that I wish they used that line at least one more time as a chorus (the song doesn’t have one). Despite being a band comprised of three vocalists, they rarely ever used vocal harmonies—potentially signaling their demise, meanwhile Yo La Tengo’s Ira Kaplan and Georgia Hubley continue to sing along with and to one another—but Gordon and Moore give it a whirl on “Cotton Crown,” the closest thing they have to a love song at this point, like two people finding each other right before the apocalypse shreds them to pieces.

“Schizophrenia” has multiple parts but never once feels stitched together, and the outro—“Schizophrenia is taking me home”—has a genuine sadness to it. The drum sound that opens the song is perhaps the most-fitting ever tone Steve Shelley could have gotten. Meanwhile, “(I Got A) Catholic Block” is top-tier riot music. Though the lyrics are all nonsense (Thurston writes in his memoir that he wanted to tackle religion but also needed to keep it obtuse enough as his views were not the band’s views), they’re delivered convincingly to make you hang on lines like “I just live forever / There just is no end,” and altogether, the nihilism of this record is articulated more succinctly and more powerfully than ever before (“I can’t get laid because everyone is dead”). Heavy smoke clouds rising out of factories, highways to nowhere, debased subway stations, skies turning red.

#17. Tatsuro Yamashita - Ride on Time (1980)

For You was my introduction, not just to Tatsuro Yamashita, but to city pop as a whole, and the guitars and horns actually do have a golden glimmer, a ‘sparkle,’ you might say. It’s pop music made for metropolitan cities: filled with images of high-end fashion, fancy cocktails and lots of sun, representing Japan at an economic high point without ever sounding excessively and boringly decadent like American and English glam rock did. Ride on Time is the better album: more consistent without the need of those pesky interludes and without a song as weak or as intrusive as “Hey Reporter!” But the songs on For You besides “Sparkle” also feel more laboured, and less natural, if you will, and I just prefer when Yamashita gets funky flushin.

He does that here, putting newcomer bassist Kiko Ito in charge of making sure songs never ever get boring. Yamashita is the first voice we hear on the album, telling Ito to ‘go ahead,’ who proceeds to lay down a bass-line that’s just plain fun. Similarly, Ito's entrance on the title track is a show-stopper: Yamashita pulling back the curtains with a piano glissando and revealing the full band to unleash the chorus, “Ride on time, さまよう想いなら.” (There are many reasons why city pop crossed over to Western audiences but one of those reasons is that it often mixed in the occasional English lyric-as-hook.)There’s so much colour on “Ride on Time”—the saxophone coming in bring the second verse back into the funky groove is a great idea; the chicken scratch guitar and backing vocals from Minako Yoshida—that its 6 minutes passes by in what feels like three.

Elsewhere, Ito’s bass squiggles on “Daydream” while Yamashita squeezes the title’s words out in his soaring falsetto: he was the Youssou N'Dour of Japan, or maybe N'Dour was the Yamashita of Senegal. “Silent Screamer” starts off with a simple drum beat, a machine revving and groaning to life that turns out to be the most bad-ass guitar ever: it’s at once the album's biggest rocker and meanest funker, and Yamashita's shout near the end is unbelievable. The second side drops the funk completely to its detriment: the album is split between its upbeat tracks and ballads in the same way as the Roiling Stones’ Tattoo You earlier this list, or say, Sam Cooke’s Ain’t That Good News, but there’s still plenty of gorgeous texture to sink your ears into even though the sentiment of the songs seem to fall into cliches: sugar babes, rainy days and kisses goodnight.

#16. Paul Simon - Graceland (1986)

Because most millennial’s fathers listened to U2 and mothers listened to Paul Simon, there’s an active distrust against these artists from young listeners that’s led to some pretty embarrassing write-offs. To wit, there are still people trying to accuse Paul Simon of cultural appropriation here, never mind that (1) he ensured all musicians were properly credited, and that they had top billing on every song they co-wrote, (2) he paid them $200/hr ($400/hr in today’s dollars) while the average rate in Johannesburg was $15 a day and (3) by recording this album, he ignored the cultural boycott from the rest of the world against South Africa due to the apartheid regime, a move that got him briefly blacklisted from the United Nations.

Oh, and for the record, if you’re the type of person to say “Oh, I prefer Peter Gabriel or Talking Heads’ version of African music,” then you’re no better than the people who use “world music” as a term. Never mind that Paul Simon was making communal pop songs here and not Peter Gabriel’s or Talking Heads’ paranoid art rock, but South African pop music that he mines here sounds totally different than west African funk that the other artists were influenced by: Africa is not a monoculture, duh. It really wasn’t until this album’s massive success that there became a market for ‘world music.’ This is why you have that term; this is why you had that little section in the back of your music retailer. It’s possible someone went from Remain in Light to Fela Kuti based on Byrne’s recommendations in interviews; it’s possible someone went from Peter Gabriel’s So to Youssou N’Dour. But it’s Graceland that opened those avenues by being a huge commercial success, which is such a huge factor in influence that a lot of people never want to consider.

The first sound you hear on the album is Forere Motloheloa’s accordion, and when Bakithi Kumalo’s bass—the MVP of the album—joins in to provide a counter-melody and the drums smack to add motion, I’m already over the moon, and that’s before Paul Simon even gets a word in. Famously, the lyrics of “The Boy in the Bubble” talk of violence (“A shattering of shop windows”), terrorism (“A bomb in the bZaby carriage was wired to the radio”), government voyeurism (“The way the camera follows us in slo-mo”), fear of technology (“These are the days of lasers in the jungle”) and lack of communication (“The way we look to us all / The way we look to a distant constellation that’s dying in a corner of the sky”), but Paul Simon approaches paranoia from not merely a Westerner point of view: I listen to these words and I can’t help but think of the South African musicians who worked on Graceland having to leave the studio before tracks were finished or else risk being arrested for violating curfew. Elsewhere, a capella vocal group Ladysmith Black Mambazo turns “Diamonds on the Soles of her Shoes” into a communal experience, and the song helped give them an international spotlight (pre-Internet, if there was any African album from the 1980s that you would’ve earned or heard, it was the Paul Simon-produced Shaka Zulu released a year later). And of course, there’s the title track (“She said losing love is like a window in your heart / Everybody sees you’re blown apart / Everybody sees the wind blow” convinces me that Simon should be considered one of America’s great lyricists) and “You Can Call Me Al,” the album’s unashamed pop moment, opening the second side with an infectious and joyous riff.

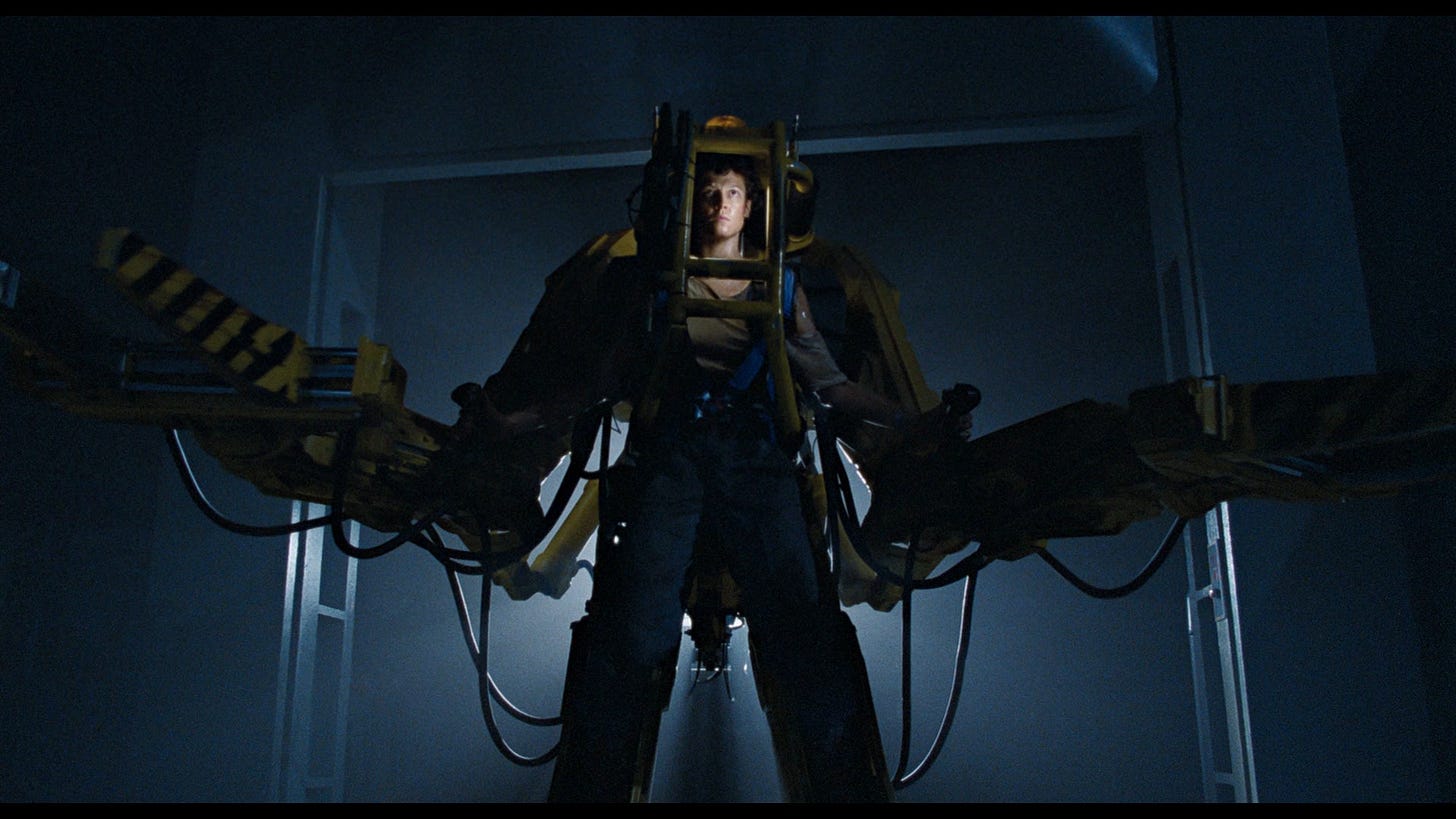

#15. Laurie Anderson - Big Science (1982)

When Laurie Anderson entertains the idea that storytelling is her strongest attribute (“I’m not really a professional anything … well maybe a professional storyteller”), it might seem like this musician being humble, but what captivates me most about Big Science are the delivery of the words more than the actual words themselves: the way she playfully swishes around the harsh sounds, one after the other, “I met this guy, and he looked like might have been a hat check clerk.” Her words can be by turns funny and despairing, “I think we should put some mountains here / Otherwise, what are the characters going to fall off of” on the title track, or when she unveils the curtains on “O Superman (For Massenet)” and reveals her mother has automatic and electronic arms, but she longs to be held by them regardless. But she’s also a great composer. “O Superman” is the happy middle ground between meditative Brian Eno and dread of Philip Glass (leading her to eventually collaborate with Glass on Songs for Liquid Days); “Example #22” rises into an ecstatic climax while a peppy horn line segues “Let X=X” into “It Tango.”

The subject of planes appears twice on the album, first on odd-groover “From the Air” as she plays the part of the captain leading the passengers through a game of Simon Says and their inevitable demise, and famously, on unlikely U.K. chart hit (#2) “O Superman,” “Here come the planes / They’re American planes, made in America,” a lyric which gained a new meaning when she performed it on Live at Town Hall: New York City - September 19-20, 2001 merely ten days after 9/11. A survivor of a plane crash—which she only talked about recently in interviews with the release of her concept album on Amelia Earhart—it’s no wonder she’d be so fascinated by them.

This is her best album by a fair margin, but I will defend the rest of her discography on my lonesome hill. Her embrace of pop music on Mister Heartbreak and Strange Angels has produced some magnificent work (particularly “Sharkey’s Day”), and Heart of a Dog was easily one of the best albums of the 2010s; helping her throughout her career was a long list of excellent avant-gardists from her husband Lou Reed to John Zorn, and pop-leaning masters like Four Tet and Peter Gabriel. The album cover looks like a photographer managed to get the exact moment this alien-auteur arrived on Earth, adjusting to her new surroundings.

#14. Steve Reich - Different Trains; Electric Counterpoint (1989)

This combines two works composed by Steve Reich, both in the late-80s, showcasing two very different sides of minimalism: pessimism through Different Trains, written in 1988 and performed by the Kronos Quartet, and jazzy optimism through Electric Counterpoint, written the year prior, performed by Pat Metheny (which makes this his second appearance on this list).

Electric Counterpoint is simply gorgeous, and I think Pat Metheny was the perfect guitarist to execute it. His needle-precise notes and the clean tone of the guitar for the main theme about 2-minutes in are like little sunshowers, and before that point, the piece does have a chug reminiscent of locomotives so it’s not totally divorced from Different Trains. Note the space in the slow movement (the shortest one here) that gets filled in during the second half where the climax makes the theme seem like it’s going faster; note the gentle nudges from the lower notes in the third movement as the main guitar does its thing (The Orb will nab that as a sample on their best song, “Little Fluffy Clouds”).

For Different Trains, Steve Reich selects samples of speech tapes that don’t just narrate the story of the Holocaust through the lens of trains, but Steve Reich selects clips of speeches that are “more or less clearly pitched” to use as the core melody for each movement, and then built the sound up around them. As Reich tells it, he used to travel frequently by train between New York and Los Angeles between the years of 1939-42 to visit his separated parents, which he recognizes later would be a very different train ride had he lived in Europe instead of America. The samples—of three Holocaust survivors—during “Europe - During the war” say a lot without giving much away: “1940 / On my birthday-”; “Germans invaded Hungary-”; “I was in second grade-”; “And he pointed right at me-”; “No more school-”; “They shaved us-”; “They tattooed a number on our arm-.” But it’s the first movement—all train whistles and his governess reminiscing about the American trains at the time—that I listen to the most, a nostalgic snapshot of America then-occupied with the war across the ocean. Eno once said that minimalism was “a drift away from narrative and towards landscape” and Different Trains—released some 30 years after minimalism first started by La Monte Young—turns the dial the other back towards narrative. Richard Taruskin argues that this piece is the “only adequate musical response” to the Holocaust, and I struggle to think of a counter in music.

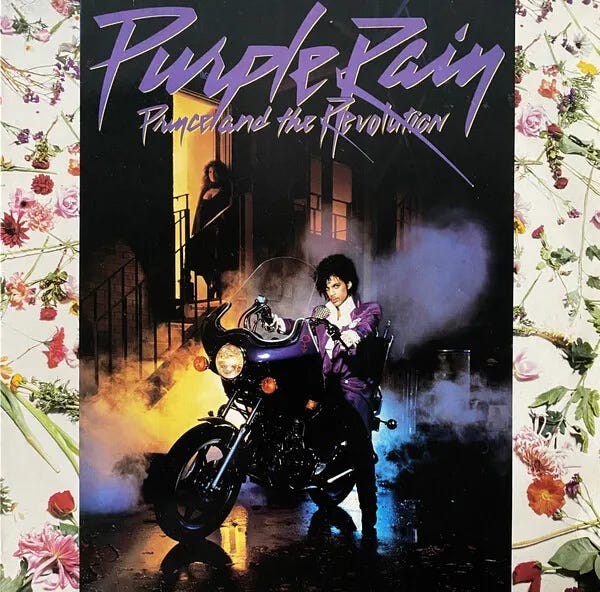

#13. Prince - 1999 (1982)

“Don’t worry, I won’t hurt U / I only want U to have some fun,” he says at the start, and there’s lots of fun to be had: this might be the best party album I know of. This is the album to use as social lubricant at your boring-ass house party; this is the one that’ll get people going on the dance-floor, the one that’ll get a collective “There’s a lion in my pocket, and baby, he’s ready to ROAR.” It’s also the Prince album that grew on me the most, whereas Purple Rain and Sign ‘I’ the Times this list stayed great in my estimation. It’s 70 minutes of what he does best: Dance Music Sex Romance.

Worth pointing out is that by this time, Prince had only modest commercial success having then scored only one Top 40 hit in “I Wanna Be Your Lover,” and that was three years ago; he was booed off stage opening for the Rolling Stones. This was his big breakthrough, and what’s interesting is that he did so with as minimal guitars as possible. The drum programming is often the lead instrument, and the first two songs alone prove just how textural Prince could get his drum machines: “1999” sounds like you’re trapped in a pinball machine and need to dance your way out, while the drums quiet down into a shuffle on “Little Red Corvette” to soundtrack your lonely walk home from the party. And in contrast to the preceding Controversy from the previous year, the politics aren’t shoved into a 2-minute filler track imploring Ronnie to talk to Russia before it’s too late: the first song is loaded with apocalyptic imagery, particularly the invocation of a purple sky as something terrifying to behold, in contrast to the beautiful hiss of purple rain just two years later.

While it might seem like the album is front-loaded—and sure, the weaker cuts are in the last two sides—given that the two big hits are right at the start, it’s sequenced quite carefully with short ones here and there to break up the long grooves. I never hear much praise for “Delirious” but that one could have easily been a single with the addicting squeal of the synth; “Something in the Water” gets paranoid and even psychedelic with that strange burbling synth line. Actually, the latter makes me think of the Beach Boys’ “Don’t Go Near the Water,” which is fitting because, like the Beach Boys, there’s a song about getting married elsewhere on the album, but in Prince’s case, “Let’s Get Married” is just an excuse for Prince to mouth-fuck the woman (“I’m not saying this just to be nasty / I sincerely wanna fuck the taste out of your mouth”). Those lines would be dirty enough—foul enough—but my favourite part is when he asks “Can you relate?” immediately afterwards in such a way that brings you into his perverse universe.

#12. Talking Heads - The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads (1982)

After establishing themselves as the best new wave group with their spectacular 4-album run from 1977 to 1980, Talking Heads eyed a new prize: the best live act that previously belonged to the Who. They have yet to be usurped. This album is the least popular of the two Talking Heads live albums because there’s no accompanying concert film, but that it’s the far better product is a no-brainer ultimately. Even from the most basic of arguments, the expanded edition of this album is a 35-track treasure trove, many of which are better than their studio counterparts, whereas Stop Making Sense’s full version is only 16 tracks, of which only “Burning Down the House” improves on the comparatively anemic studio version. And if it’s cheating to consider the expanded versions, then stated outright: the original track-list of Stop Making Sense sucks, leaning far too heavily on their worst album at that point. But The Name of This Band is Talking Heads ultimately presents a lot of songs that are far superior to their studio versions, even despite the fact that Brian Eno doesn’t produce them, but it also presents them chronologically so we get to watch them grow tighter and tighter in “real-time.”

Their debut is clearly the worst of their first four albums and much of that has to do with the production: without Eno, it’s dry as a punk album from that era but they weren’t a punk band. Here and live, it gives those songs more room to, not just breathe, but groove since they were the rare new wave band to acknowledge black music (i.e. there’s almost no blackness in the music of Blondie or Elvis Costello or Joe Jackson). The rhythm gets more supple on “Don’t Worry About the Government,” a song that wasn’t a highlight on the studio album but shines here, letting the commentary of American suburban life come through. Similarly, “Stay Hungry” knocks the More Songs version out the park; being twice as long, it feels like the natural successor to the Velvet Underground’s louder songs from the quiet third album, especially when that organ comes into play. (Talking Heads: taking the minimalism and groove of the Velvet Underground and emphasizing the groove aspect.)

Byrne is hilarious throughout: the way he belts out “I FEEL LIKE SITTING DOWNNNNNNNN” as if both a question and an exclamation on “New Feeling” had me in stitches the first time I heard it, while the way he seethes “Some people don’t know ssssshhhITTT about the (air)” on “Air” makes it better than the version on Fear of Music. “I Zimbra”’s groove here feels far more bracing than Eno’s more atmosphere-focused production. Two cuts from Remain in Light appear on the fourth side, and both “The Great Curve” and “Crosseyed and Painless” are longer and feel denser than their studio counterparts, and thus, emphasizes the influence from Fela Kuti while still rocking out. Ultimately, the energy gets to the point that I don’t even miss the funky brass arrangements that elevated “Love → Building on Fire,” for example. If the lack of a visual bothers you, just imagine Byrne dancing and you’ll see why it’s better than Stop Making Sense.

#11. Djeli Moussa Diawara - Djeli Moussa Diawara / Yasimika (1983)

First released in France in 1983 and not made available in America until its reissue in 1990 with a new cover and title (Yasimika), it’s understandable if you haven’t heard this yet. Especially given the confusion with the Anglicized version of his name—Jali Musa Jawara—when musicologist Charlie Gillett released it in the UK (Gillett tells a funny story that World Circuit brought the Diawara to perform with Ali Farka Touré, but they hadn’t heard of each other before to the shock and bemusement of everyone who assumed(?) that two African musicians ought to, never mind that Diawara was from Guinea, and Touré is from Mali).

Here’s a sentence for you if you need convincing: the opening song, “Fote Mogoban” is the best song from Africa that I’ve heard, and is enough on its own to rank this entire album as highly as I do on this list. After a brief kora run, Diawara pleas to the sky, which opens up and answers him in the angelic voices of the other vocalists. I listen to that first 25 seconds or so almost daily: the contrast between his vocals, cracked and wearied, with the backing vocals, sweet, pure and even innocent, is simply enough to stop me in my tracks despite the language barrier.

The template for all of Yasimika’s four songs is an interplay between the kora—a west African instrument that cascades and washes like the harp—and guitar, which is backed by balafon, an African percussion instrument whose sound I liken to the marimba. (The balafon was an instrument that no doubt Diawara grew up hearing because his father played it.) Add the sky-gazing vocals sung from both Djeli Moussa Diawara himself and a chorus of backing vocals from three others and voila! I’m confused by the continued popularity and acclaim of the purely instrumental albums from fellow west African kora player Toumani Diabaté where there’s so much less. When Diawara lets his kora ring over the balafon on “Haidara” and “Yasimika,” the effect isn’t just for us to admire the technicality of his playing, but how the sounds blend together to sound like magenta raindrops falling gently on the beaches of the Ivory Coast where this was recorded.

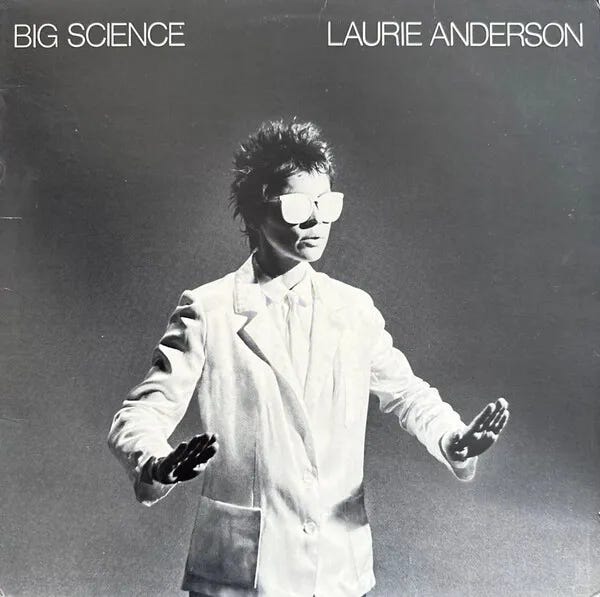

#10. King Sunny Adé - Juju Music (1982)

Bob Marley passed away in 1981, and Island Records cynically hoped that King Sunny Adé could be their next big crossover, and while they struck gold, it was perhaps not on the level that they wanted. But I thank them anyway because Adé’s music—jùjú music—is like Nigerian reggae by synthesizing elements of highlife by way of its bright and shimmery guitars, African polyrhythms, and with a healthy dose of country in there thanks to the pedal steel guitar which Ade helped popularize into juju music. There’s a universal appeal to this music where neither melody nor groove (rhythm) are emphasized over the other. I loved this album the moment I heard it, the only question was ‘how much,’ an answer that keeps increasing every time I think about it.

Parisian producer Martin Meissonnier is credited with helping Adé crossover, and Meissonnier did what any person would do with African music when tasked to help it sell CDs in America: he broke up the groove into pieces, asking that Juju Music be comprised of miniature grooves a.k.a. actual songs. His other contribution here is adding synthetic instruments which would be more pronounced on follow-up Synchro System and Aura, but are thankfully reigned in here. The drum machines are hard to spot and often just lock into the established groove from the multiple drummers, while the synths mesh with the pedal steel guitars to add a dubby psychedelia to the mix.

Adé was one of the very, very few people to hear a pedal steel guitar and not hear country, but rather an instrument capable of an alien-synthetic sound, and so the pedal steel throughout Juju Music sounds like UFOs hovering off the Earth’s surface for a moment and then shooting off into space. Friendly aliens, just so we’re clear. Meanwhile, the other guitars have a liquid gold tone to them that is far richer than those commanded by Youssou N’Dour or played by Dibio “Machine Gun” Dibala covered earlier this list.

#9. Public Enemy - It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988)

The most physical bracing rap album ever concocted. The ensuing 35 years have given us producers that have been able to imitate the noise but not the physicality. And while there have been plenty of rappers to match Chuck D’s brutalist approach on the microphone, not like they ever rapped on beats this good anyway. I’ll plug here that Public Enemy’s debut, Yo! Bum Rush the Show, is one of those debut albums that was absolutely extraordinary but unfortunately underrated because the artist went on to release a classic almost immediately afterwards—see also: Bob Dylan’s debut—and there are a total of 9 rap albums on this list, and I could conceivably make a case for Yo! for #10.

The song titles are almost all call to arms—“Bring the Noise”; “Don’t Believe the Hype”; “Louder Than a Bomb”; “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos”—and the group’s intentions to make Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On for rap music very clear from the outset. In response to hip-hop naysayers who thought all rap music was just black noise, Bomb Squad responded by increasing the noise to a maximum. Consider this the turning point in rap beat-making where it was no longer enough to rap over trusty James Brown drum breaks and a single other sample. Bomb Squad’s Hank Shocklee—“the Phil Spector of hip hop,” Chuck D reckons—built up a “wall of noise” on top of them by adding a ton of other sounds to the mix so that every song feels ready to explode.

Case-in-point is “Night of the Living Baseheads” where the noise builds and builds, and just as you think Bomb Squad might be reaching towards a wall—a point that they can’t possibly build past—they drop the Temptations’ “Hold it, listen!” from “I Can’t Get Next to You” before piledriving even more samples on top, including one from ESG’s debut EP. Elsewhere, “She Watch Channel Zero?!” famously samples Slayer in a way that not even Rick Rubin—great early hip-hop and Slayer producer—would have thought of while the blown-out basement vibe of the “she watch—” hook gives birth to El-P. Meanwhile, “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos” contains what surely remains one of the greatest rap verses of all time. All of the funk rhythms have a rock heft to them, and the jazziness feels like the avant-garde attack of Ornette Coleman or John Coltrane. The album’s righteous rhythms would make their way west and manifest themselves through N.W.A., while producers on the east coast would take its rigorous sampling and apply it to more psychedelic ways the following year.

#8. Minutemen - Double Nickels on the Dime (1984)

Minutemen was hardcore that liked a funk bass-line, jazz drumming and a jazz solo; there are D. Boon’s solos that play like a saxophone player that made the leap to electric guitar and basically played it the same way. That being said, don’t mistake them for an art band. They were the anti-art punk band. Wire, who had fully embraced being the band of art students that they were, notably disposed of the guitar solos for Pink Flag, an album that had a notable influence on Minutemen in terms of song structure and song length. By contrast, Minutemen kept the lengths the same, yet still made room for solos. Only if they heard mortar shells, maybe.

Contrary to most popular double albums, the appeal of Double Nickels on the Dime is not that they cover a wide range of genres: an acoustic instrumental is as ‘diverse’ as this album gets. The appeal of Double Nickels is that there are over 40 songs of basically the same song over and over, each one a song that feels like the greatest thing in the world while it’s happening. The best songs are stacked on the first half. “Viet Nam” plays like a souped-up Commodores song the moment Mike Watt puts an end to the barraging intro with a single note and starts the groove. “Cohesion” is absolutely indispensable, resetting the album while also looking ahead to the slower, quasi-psych wash of “Do You Want New Wave or Do You Want the Truth?” just around the corner. The opening 30 seconds or so as “Corona” are what it feels like to put the lime in the bottle and then drink some on a blistering hot day. And of course, the album will forever be fondly remembered because there has been no more vital set of five words in underground/indie culture than “Our band could be your life.”

It’s true that the band put all the weak songs on the last side, but that being said, the reject pile has one of the album’s five best songs on the whole album in “Jesus and Tequila,” so just how chaffy could it be? Their cover of Steely Dan’s “Dr. Wu” is cute with its harmonies in their completely unrehearsed glory that somehow makes the song’s mysterious “Katy lies, you can see it in her eyes” feel that much more poignant. “A richer understanding of what's already understood” is what happens to me every time I visit this album, finding something new to love each time. At the same time, “I’m fucking overwhelmed!” also applies.

#7. La Monte Young - The Well-Tuned Piano (1987)

On the one hand, the four major minimalists—La Monte Young, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Terry Riley—sound nothing like one another. On the other hand, La Monte Young doesn’t belong with the other three regardless. Dubbed the father of minimalism because he began writing compositions in that style well several years before the others, his drone music doesn’t have the same rock/pop-friendly pulse as do the others, and there’s a vastness to his music that the other three don’t come close to. (He once said he loved California’s “sense of space, sense of time, sense of reverie, sense that things could take a long time, that there was always time,” and those words apply to all of his music.) As a result, the other three’s influence on rock music feels more explicit to me even discounting the Who all but namedropping Terry Riley or Captain Beefheart referencing Steve Reich, whereas Young’s mark on rock was because of the Velvet Underground connection: his Theatre of Eternal Music collective included a young John Cale who brought La Monte Young’s drone into rock.

The problem with La Monte Young is that try as though I might, I’m not going to beat Kyle Gann here, who has got the best words on, let’s see, Giacinto Scelsi, John Cage, Morton Feldman, and La Monte Young, so I’m just going to quote him wholesale, “That oneness with sound and existence, sought by yogic meditation, is a highly alert state, very different from the semiconscious, hypnotic trance that was so long assumed to be the aim of minimalism that it became self-fulfilling.” (That passage comes from the essay “Maximal Spirit” which you can find in the Music Downtown collection.) Where Glass invited listeners to walk in and out of 4-hour Einstein on the Beach, I see no such instruction on Young’s 6-hour The Well-Tuned Piano; his music feels less pop than the rest of the minimalists, who sometimes felt like they were making pop music without actually having the spine to admit that’s exactly what they were doing.

La Monte Young first began composing The Well-Tuned Piano in 1964, and it wouldn’t be for close to another decade before he premiered it, and it wouldn’t be for close to another decade before he finally released a commercial recording of it to the world. Not that anyone could have tried to perform it themselves in the interim if they wanted to. For one thing, it takes weeks to tune the piano to Young’s just intonation specifications. For another thing, he kept the tuning a secret such that no one would be able to figure out how the piano was tuned exactly. And it’s fully improvised—Young got his start playing in Los Angeles alongside cerebral thinkers Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, and Eric Dolphy, and he once beat out the lattermost in an audition for the Los Angeles City College jazz band—such that each time he performs it, it’s different, so it’s technically unfinished (very Kanye of him) and infinite, like the universe. My suggestion with how to approach a piece this size is the same as the lengthy pieces of Morton Feldman: you just hit play and immerse yourself. The way I see it, if you love music, then you love sound; and if you love sound, then you’ll love this because it’s six hours of pure sound.

#6. Steve Reich - Tehillim (1982)

When Steve Reich recorded a Pentecostal preacher saying “It’s gonna rain!” and played it back on two tape decks, he didn’t realize the tapes weren’t synchronized properly and one was going faster than the other. You see this phenomenon of phasing, where one musical element goes “out of phase” with the other, everywhere just sitting in traffic in a big city if you look at your car’s blinkers with the car in front of you’s — assuming a different make or model. They might blink together, but then one of the cars’ blinkers will go faster than the other, but eventually they’ll ‘reset’ and be back in unison, and then fall out of phase again, and so on. He took this seemingly tiny idea and developed it into a greater notion of “Music as a Gradual Process” where you can hear the process happening throughout the music.

What makes Steve Reich the best of all the minimalists was that he applied phasing and this idea of perceptible processes far further than did the others did theirs, precisely because he didn’t ‘sit still’ from composition to composition. Tehillim—his first composition in the 1980s—for example, is his first-ever work to embrace his Jewish heritage (its title is the Hebrew word for “Psalms”), and in a way, I don’t think we would have gotten to Different Trains where he ruminates on the Holocaust if we didn’t get Tehillim first. And by extension, I don’t think we would have gotten to Different Trains if he didn’t return to making sociopolitical music on The Desert Music earlier this list. And if we didn’t get Different Trains, we wouldn’t later get WTC 9/11.

As I wrote for The Desert Music, it tends to be underperformed and under-recorded—if not straight underrated—because of its complexity: four voices, six percussionists, organists, and a chamber orchestra. The two electric organs remind me in their eventual entrance in the first part of the crushing mass of Four Organs, except by halving the number they’re only adding to the density of the four voices. But what makes it extra difficult, and extra groovy, is that there is no fixed meter as Reich points out, “The rhythm, of the music here comes directly from the rhythm of the Hebrew text and is consequently in flexible changing meters.” A challenge for singers: sing along to the women while also trying to tap out the beat.

#5. Kate Bush - Hounds of Love (1985)

Kate Bush’s previous album, The Dreaming, was her ‘personal exorcism,’ pulling from modern horror films that enabled her to lean into a never-before-seen madwoman persona. It was also almost rejected by her label EMI for the lack of hits, and notably sold less than its predecessors. Hounds of Love came out after a longer break than her previous albums and is a shift away from The Dreaming’s dense production. It bridges the divide between her own vision and what the label/audience wanted by… literally dividing the album into two. The first side is packed with hits to appease EMI: four of its five songs were released as singles, and all of them fared well on the UK charts, with “Running Up That Hill” scoring her a hit across the ocean as well. The second side is decidedly anti-hit by contrast, a song-cycle dubbed “The Ninth Wave” taht enables her to explore different sonic territories from Irish jigs (“Jig of Life”) to ambient soundscapes (“Hello Earth”).

My hot take is that by organizing the second side into a medley, it lets her get away with not trying to bother with the first side’s divine songwriting: it was wise to keep the first two songs as short as they are because the minimal arrangement of “And Dream of Sheep”—although note the acoustic guitar near the end—makes it feel plain compared to what we just heard; the strings of “Under Ice” are deeply portentous but also simple in their harmonies. But “The Morning Fog”—one of the few songs in the second half that works well in isolation—is the sort of song that I play over and over whenever I reach for it so that I can hear Bush list her family members with a hiccupping vocal that makes me think of Peter Gabriel on Genesis’ “Supper’s Ready,” “I’ll tell my father / Huh-oh, huh-oh!”

But the first side is the best five-song run of the decade. As Kate Bush starts singing on “Running Up That Hill” over the tango of the swelling synth and massive drum machines, I’m already gone: out of my shoes, out of my soul, and floating out of body. Her love of horror shines through with a sample from Night of the Demon opening the title track, “It’s in the trees, it’s coming-” which leads into a drum drop that makes you feel like you’re being chased through the dark forest. “The Big Sky” is intense in its mass of sound and only builds from there with handclaps that sound thick as drums, roving electric guitar, and a chorus of Kate Bushes; the only breathing room is a brief pause — for the jets. “Cloudbusting” has a magnificent string arrangement that blossoms into a beautiful melody during the choruses that makes the line, “I just know that something good is gonna happen,” silly because that good thing is happening right now! The only song on the first side that was not released as a single is “Mother Stands for Comfort,” and it’s one of the album’s most interesting compositions as Kate Bush sings as the mother of a murderer, “Mother stands for comfort / Mother will hide the murderer / Mother hides the madman / Mother stays mum” (note the double meaning of the last line). It’s German ECM-bassist Eberhard Weber that makes the song so special, providing tasty counterpoint with his double bass to the point that it feels like the two are doing a slow dance with each other while the industrial textures around them—whip cracks and broken glass—are the violence of the lyrics realized.

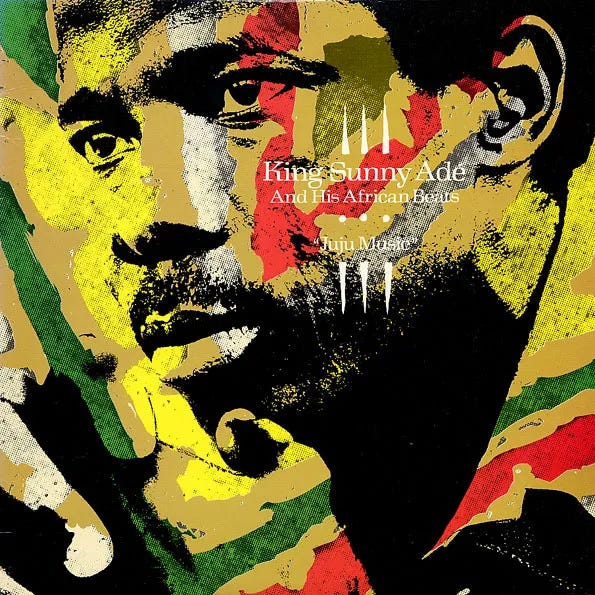

#4. Prince - Purple Rain (1984)

Prince’s previous hit, “Little Red Corvette,” only peaked at #6 on the charts, and he might have been remembered as a one-hit wonder, short king, and sexual novelty had he failed to follow it up. What happened instead was that he laid claim to King of Pop with Purple Rain, no matter if his title was ‘merely’ Prince—how can Michael Jackson have that title, if his discography is so shallow by comparison?—an album that effortlessly blends together funk, hard rock, and soul into a version of purple pop music that only he seemed able to craft.

Thanks to his vision, the album never falters, though the second and second-last tracks utterly pale in comparison to the bookends—“Take Me With U” does that have that formidably tense introduction/bridge—and it peaks again in the middle where it seems to play like a greatest hits compilation. “Computer Blue” starts incredibly sexually and then effortlessly blends a funk groove with Prince’s rock guitar, and the stretch at the 1:40 mark takes the song to a more exciting new place as if that were possible. “Darling Nikki” is gets filthy from the get-go, “I met her in a hotel lobby / Masturbating with a magazine” and only gets filthier from there as Prince brings in sex toys and consent waivers. And in “When Doves Cry,” Prince got his first actual #1 hit, and not only are the xylophone plinks in the background—imitating the sound of a dove crying—simply gorgeous, the fact that Prince pulled the bass from the song was tests the waters for how unconventional his hits could be.

Over sustained church organ chords, Prince-as-preacher announces, “Dearly beloved We are gathered here today / To get through this thing called life,” and eventually the 80s’ drums come in, and Prince was one of the very, very, very few artists that could make those drums sound alive. The words in the spoken intro aren’t even all that special, mostly clichés, but they are delivered convincingly that you might believe they’re not. As Prince-as-preacher finishes his sermon, Prince-as-Rock-God emerges, the drums rattling around like you’ve shrunk down and are stuck in a pinball machine. The drums will make you want to dance your way out, and it isn’t until the cathartic guitar solo makes it clear you have to rock your way out. It’s one of the best openers of the decade, and yet, as far as this album goes, it only gets silver to the title track, which is the best closer of the decade.

#3. R.E.M. - Murmur (1983)

Sonically, R.E.M. took the Byrds’ jangly guitars and applied it to the drum patterns of late-70s post-punk, and they perfected this sound called ‘jangle pop’ before the Smiths put out their first album. They were also a democratic band with no member more important than one another; whereas some rock bands’ rhythm sections exist to serve the singer (see: the Smiths where Morrissey dominates the mix), Michael Stipe’s vocals were no more the focal point than Peter Buck’s guitar or Bill Berry’s drums, and the term ‘backing vocals’ was a disservice to the emotional and physical counterpoint that bassist Mike Mills added to their songs. At least, this was true until their contract with I.R.S. expired and then signed with the majors and became a different band.

There’s a despair on debut album Murmur, lurking just beneath the surface. The lyrics here aren’t inherently sad by themselves, but channeled through Stipe’s cared singing, they become so much more. At this time, Stipe was comparable to Cocteau Twins’ Liz Fraser except there was never any doubt that Stipe’s lyrics were in English, but they were still shrouded in mystery except on the occasion where flashes of anger came through: the climax of “Sitting Still” has him going “You could get away from me” and then suddenly snapping “GET AWAY FROM ME.”

They were also eclectic for an indie band: the metallic clangs on “Radio Free Europe” are generated from a vibraphone while “Perfect Ballad” is really brought to life by producer Mitch Easter who takes what would otherwise be a simple piano line and turns it into a stranger sound by harmonizing it with an out-of-tune upright piano while Stipe’s lyrics feel like a series of disconnected images and phrases—“Eleven shadows way out of place”—that maps out a sadness as Stipe details social anxiety (“Shoulders high in the room”) and retreat (“Standing too soon”). Any doubts that it’s a post-punk album through and through should be quashed by the opening 12 seconds of “Laughing” where they channel fellow Athens band Pylon, while Peter Buck’s guitar on “9-9” folds in the angular lines of Gang of Four. “Did we miss anything?” An innocuous line the first time you hear it, but then he bellows it out later, “Did we miss anythaaaanahh,” making it very clear that we—them, all of us—have indeed missed much.

#2. Prince - Sign ‘O’ the Times (1987)

Double albums let artists show off their ambition, usually by demonstrating everything that artist learned at that point in time. Prince’s second double album doesn’t do that. Instead, at it’s best, it’s ambitious because it’s low-key and spare, letting Prince’s singer/songwriter talents shine. Where was there left to go, exactly, after he conquered pop music from 1978-1984, and then after he tried his hand at making his own Sgt. Pepper’s on Around the World in a Day? After disbanding the Revolution, Prince subverted expectations here by making what sounds like a solo album at times. Case in point is my favorite Prince song ever, “The Ballad of Dorothy Parker.” I’ve never heard drum machines used in the way they’re used here, in tandem with Prince’s voice as the lead instrument and not used as traditional percussion, which enables Prince to do some of his most inventive singing on the record—which is saying a lot—thanks to all the space the machine provides: “BRRRRRRING! The phone rang and she said WHO!... / …ever’s calling can’t be as cute as you.”

Likewise, the title track feels like hip-hop by way of Prince as he tackles social commentary in a manner that’s way more lucid, “In France a skinny man / Died of a big disease with a little name / By chance, his girlfriend came across a needle / And soon she did the same,” is how the song starts before singing “Oh why…” in a way as if he knew the couple personally. These songs demonstrate a vulnerable side of Prince that we haven't seen (much of) before: Prince the Sex God and Prince the Rock God now becoming Prince...the Folk God? Well, why not?

“Starfish and Coffee” makes me think of “Dinner With Delores” on (contract-ful)filler album Chaos and Disorder since both are merely (‘merely?’) tuneful cuts with surprisingly sweet singing from Prince. “The Cross” is one of the best crescendos of the decade—even more than U2 that same year with Eno; even more than Talk Talk’s post-rock to come—and the sitar that comes in late to re-state the melody is a surprise that I’m personally never ready for. “Play in the Sunshine” is just pure, colourful funk that I’d like to describe as “kaleidoscopic” except that might take away from how fun it really is with Prince urgently stutter-commanding “We gotta dance every dance / Like it’s gonna be the last time!” or the 8-word short story in “Meet you / Kiss you / Love you / Miss you.” And plenty more career highlights to boot, all within the same album!

#1. Sonic Youth - Daydream Nation (1988)

You can love Sonic Youth because they were an integral part of post-punk becoming indie rock becoming alternative rock. You can love Sonic Youth because they were scary, noisy, and eventually even poetic about their noise. You can love Sonic Youth because they were curious about the avant-garde, and their method of preparing their guitars—shoving drumsticks into the fretboard—was inspired by John Cage. You can love Sonic Youth because they laid claim for being the most consistent band during the three decades they were active.

What I love them for is that you get to grow up with them. Art school brats to teenage riots to their young-adult grunge phase, and then they settled down into the suburbs, and raised a family. If you go just a little west of New York City to Hoboken, you get a very similar feel in Yo La Tengo’s discography, who usurped them for claim of most consistent band after Sonic Youth disbanded. And in a way, I did grow up with them. I was twenty, just getting used to the idea that there was a culture on the internet of rating and writing about music, and found Daydream Nation on a list of records that Pitchfork gave a perfect 10.0 score to (at the time, there weren’t many of them). I had just gotten my first corporate job, with its towering gray cubicle walls and one-hour commutes, and I must have listened to that album every day on the way home to feel cleansed by its strangely-warm noise.

Daydream Nation is long at over 70 minutes, aligning it to what the Cure will soon do on Disintegration; both albums have a feel of their respective bands looking at all they achieved in the preceding decade and going even further. There’s no filler this time, not a single song I would remove; not even “Providence,” a much-needed reprise from the non-stop assault of the preceding seven tracks. Near the end of “Providence,” the piano cuts out and you’re left with noise generated from an overheated amp; that’s the ‘theme’ of the album if there is one, which is an urban loneliness and social disconnect. What’s the solution? Teenage riot, of course. Steve Shelley’s drum hits crisper than ever as the songs barrel through extended lengths. Meanwhile, Kim Gordon is more articulate about her anger than ever, targeting sleazy corporate male bosses on “Kissability” and consumerism (doubling for prostitution) on “The Sprawl.” Lee Ranaldo hands in three songs this time, more than ever before, including a loving tribute to Joni Mitchell with a guitar part that has a melodic whimsy, and the introduction to “Rain King” is the heaviest moment on the album tied with the noise section of “Candle.” The best songs are the bookends, long and tuneful “Teenage Riot,” and then short and stomping “Eliminator Jr.” that marches towards the inevitable nowhere.

![Cover art for Ride on Time by 山下達郎 [Tatsuro Yamashita] Cover art for Ride on Time by 山下達郎 [Tatsuro Yamashita]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4AwZ!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F33aef1a1-1c8b-46ef-bf59-b1401122df19_600x591.webp)

strongly disagree with the statement “ (i.e. there’s almost no blackness in the music of Blondie or Elvis Costello or Joe Jackson).” Heart of Glass is a disco song. Rapture of course has a rap on it, an over-long rap but nonetheless. Listen to Elvis Costello’s Get Happy! then listen to Otis Redding or Sam Cooke. Joe Jackson’s swing and jazz albums owe more to Duke Ellington than to Benny Goodman. They might not sound like Sly Stone, but there’s plenty of groove in their music.

Love this list! Prince having two entries in the top 5 speaks to his genius and his towering influence on the decade. Not to mention that they both contain some of the best pop songs ever. Bravo!