Here’s the rundown of what makes Joni Mitchell the Greatest:

(1) She is, with zero doubt, the best artist that Canada has ever produced, born in a tiny town called Macleod, later renamed Fort Macleod.

(2) She is one of the best lyricists. Top two. Certainly the most romantic one: Mitchell’s best songs expressed a vulnerability—when asked once what some of her songs meant, she pointed out that the meaning is right there for everybody to see—that is honest, compelling, and also deeply poetic despite the fact that she made the conscious decision to move away from more ‘obviously’ poetic prose and imagery early on. Bob Dylan winning the Nobel Prize for literature makes sense to me, but then you’d also have to give it to Joni Mitchell, whose lyrics mean more to me as poetry than do the poems of Louise Glück, for example, who won the Nobel after Dylan.

(3) She is one of the best guitarists. Having contracted polio at a young age, the disease weakened her left hand and rendered her able to play conventional chords for long periods of time, so she alternated the guitar’s tuning to work for her, creating a secret guitar language and sound that was secretly-complex, and by turns, warm, beguiling, and even orchestral; no wonder she was revered by Sonic Youth.

(4) She is one of the first female auteurs within music, by being one of the first to turn her back on what audiences and critics wanted her to do, and it’s not surprising that her stranger, less popular albums have been championed by the likes of Prince and Björk.

(5) She’s sharp and witty, even outside of her music. In interviews, she pointed out hypocrisies amongst critics, who lambasted her for turning to jazz but celebrated Steely Dan for doing the same afterwards, and once correctly identified why there was so much mediocrity was that there used to be a segregation of duties between someone who wrote the song and someone who sang it, instead of the same person doing everything even if they didn’t have the talents. Her description of Wayne Shorter’s “Nefertiti” helped me fall in love with it, “It evokes the image of a late night in New York City; some guy is coming up from Chinatown and he’s drunk and he’s kicking over garbage cans and yelling all the way uptown.”

(6) She forged a path for female artists to express themselves artistically, romantically, and sexually by being authentically herself.

Here’s the guide:

David Crosby produces Song to a Seagull, and his intent was to strip Mitchell down to just the essentials, but he was not a trained producer, and ultimately used too many microphones that captured a ton of hiss. Engineer John Haeny was tasked to remove the hiss but at the cost of some of the range on the high end, resulting in a sound that can sometimes feel flat. Add to this that Mitchell hadn’t yet discovered her personal style; the lyrics are far more poetic than they’d be later on, and the intrusive psychedelic detour on “Nathan La Franeer” that doesn’t come off. So I understand that people sometimes gloss over this one, but “I Had a King” and “Night in the City” rank among her best songs. There’s a deep power in her vocals on the former when she sings “He’s taking the curtains down,” and already some of the words point to the incredible lyricist around the corner: the mere notion of “having” a king; the juxtaposition of keys fitting in doors and thoughts fitting in men; rooms having “an empty ring.” The guitar of “Night in the City” bristle and chirp to bring to mind exactly what Mitchell is singing about; love the playful whine she does when she sings “Must you get ready so slow.”

Clouds is better, but it leads with its weakest track—either that or the a capella one—but “Chelsea Morning” and “Both Sides Now” are two of her early masterpieces. The former’s alt-tuning chords give it a chime that really feels like waking up in an apartment in the greatest city in North America (would recommend venturing over to Jack’s Wife Freda for brunch), while the latter plays like a children’s book at first, expressing both the good and bad about clouds before looking at love from both sides. The verses leverage simple internal rhyme, “Moons and Junes…”, only to pivot into newer rhymes in a way that makes the mature song still feel appropriate for children, “…and Ferris wheels / The dizzy dancing way you feel / As every fairy tale comes real.” (By contrast, her songs after 1974 won’t that sing-song and simple-rhyme quality that make them seemingly simple yet endlessly sophisticated.)

Ladies of the Canyon is either a good album propped up by its last three songs, or a great album held back by its middle section that’s a little too heavy on the piano — I haven’t quite decided which, but I’m also sure it doesn’t matter either way. “The Arrangement” builds its chorus around a silly rhyme scheme—“You could have been more / Than a name on the door / On the 33rd floor”—and it could’ve benefitted from a smoother vocal, which is a shame because the introduction is quite pretty. “Rainy Night House” is about her relationship with Leonard Cohen, but the details are hers and hers alone, and though Mitchell has clarified that the lines “You sat up all the night and watched me / To see who in the world I might be” were something that really happened with Cohen, for me, it was better kept between the two; “Willy,” about her relationship with Graham Nash, fairs better because I had never considered the idea of a lover as a child and father at once. The guitar pings of “Morning Morgantown” feel like the sun kissing a sleepy town as it rises—I can’t imagine better morning alarm music—but the album’s best songs are all at the end. “Big Yellow Taxi” the tightest, catchiest pop song I can think of about social awareness; the high-pitched “please” at the end of the third verse is such a lovely sound. (Some moron will tweet on X every year about how “tree museum” should have been arboretum proving that people didn’t deserve Mitchell at her best.) “Woodstock” is led by its haunting organ chords, and the chorused “And we got to get ourselves back to the garden” feels as much a warning as it is a hippy call to nature. “The Circle Game”’s choruses actually do have a “round-and-round” and “up-and-down” feeling thanks to its melody.

Ineffable, infallible, impossible Blue. This album contains, at the very least, the most beautiful way anyone has ever said the word “Blue,” “California,” and “Canada.” (I had first heard “Blue” through a sample on Blu’s “My World Is…” and assumed it was a soul singer. Imagine my shock that to hear it on this singer/songwriter album.) Blue addresses the central issue of Ladies of the Canyon by having Mitchell play more Appalachian dulcimer and less piano, and spacing out the piano tracks instead of having them all in the middle stretch. That, and the piano songs here are simply better anyway. “Old Man” ends with a chord melody that’s hopeful; naive, even, as she looks fondly back at her relationship with Graham Nash. (Noticing the bed being too big post-breakup feels like a common thought, but this song is the first time I’ve heard it articulated that the frying pan becomes too wide.) Meanwhile, “River”’s piano chords evokes the snowless Christmas she sings about.

True, she turns completely inwards here. There are no more songs like “Big Yellow Taxi”—where the focus was not on her despite the significance of the title—or “Woodstock” except a passing line on “California,” “Reading the news and it sure looks bad / They won’t give peace a chance / That was just a dream some of us had.” This might have been a loss except she’s the best to ever do personal love songs. “Would you take me as I am / Strung out on another man?” Vulnerable. “I wanna talk to you, I wanna shampoo you / I wanna renew you again and again?” Delightfully absurd. “If you want me, I’ll be in the bar.” Yeah, well, he probably deserved it. “All I Want,” about James Taylor, whom she was in a relationship with at the time, feels like a response to Bob Dylan’s “All I Really Want To Do” to me. Dylan: “All I really want to do / Is, baby, be friends with you.” Mitchell: “I wanna talk to you, I wanna shampoo you / I wanna renew you again and again.”

For the Roses gets the least amount of attention of any of her classic albums, but I think it’s her second-best album. For one thing, her words are some of the most scorching of her career, especially compared to a marked passivity that would start to arrive later on. The album’s single “You Turn Me On I’m a Radio”—written only to appease David Geffen who challenged her to write a hit—is a love song that makes room for this putdown, “I know you don’t like weak women / You get bored so quick / And you don’t like strong women / Cause they’re hip to your tricks.” Elsewhere, on “Woman of Heart and Mind,” she puts down a lover’s shallow lifestyle, “You’re always disappointed, nothing seems to keep you high / Drive your bargains, push your papers, win your medals, fuck your strangers / Don’t it leave you on the empty side?” (When my dog grew into her smile, the line that came to mind was “Do you really smile, when you smile” from that same song, because with dogs, there’s never a question.)

She intended for the cover to be a drawing of hers depicting a horse with roses sticking out of its ass, representing her feelings about the music industry. Instead, we got a picture of her outside, which actually does give clues about the music therein: consider For the Roses as the heartbroken Blue going outside for the first time in a week. It’s another intimate album, but there’s more colour, texturally: woodwinds on “Barangrill”; a second guitar crashing into hers creating the rush of movement on “Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire”; saxophone on “Let the Wind Carry Me” pointing ahead to her shift into jazz soon to come; unexpected bursts of strings on closer “Judgement of the Moon and Stars (Ludwig's Tune),” her most ambitious composition yet.

It’s the 3-song block between “Electricity” through “Blonde in the Bleachers” that I’ll forever cherish. “Electricity” begins by floating into the scene over a pillow of backing vocals that disappear so that Mitchell’s words are allowed the room that they deserve. By inventively naming a character ‘Minus,’ she gets away with the lyrics “She don’t know the system, Plus / She don’t understand,” as well as just driving the electricity image home by incorporating words that you wouldn’t expect in a love song, “She’s got all the wrong fuses and splices” and “Conducts little charges / That don’t get charged back.” “You Turn Me On I’m a Radio” starts like Bob Dylan with the harmonica (courtesy of Graham Nash) that takes up the first fifteen seconds before she does her most direct singing and lyrics, “Driving into town with a dark cloud above you / Dial in the number that’s bound to love you / Oh honey, you turn me on, I’m a radio.” So far, this could’ve easily been on Ladies of the Canyon or Blue, but after the self-deprecating, “I’m a country station, I’m a little bit corny,” Mitchell sings, “I’m a wildwood flower,” which is joined by the same backing vocals of “Electricity” and it really brings to mind images of a flower blooming in fast-forward. “Blonde in the Bleachers” has Stephen Stills coming in with drums to the line “You can’t hold the hand of a rock and roll man,” which will not be the only case on a Joni Mitchell song where a very famous male musician shows up for only a few seconds before stepping aside immediately afterwards.

Court and Spark trades folk for expertly-crafted pop songs that she would never essay again despite the album’s success: it hit #2 on the US Billboard charts and “Help Me” was her only single to be in the top 10 (insulting to think about, given the strength of so many singles before “Help Me”). The first half is pop perfection: the melodies of “Help Me” and “Free Man in Paris” feel effortlessly catchy, and I long to listen to the latter when I eventually make my way to Paris so I can feel “unfettered and alive.” “Other People’s Parties” has this tidbit of wisdom, “Laughing and crying, you know it’s the same release,” and at the end of the song, Mitchell overdubs vocals going “Laughing it all away” in a manner that reminds me of a Cocteau Twins song circa Heaven or Las Vegas: layering into a carousel of voices. Some sound like they’re laughing (the higher pitched ones) and others (Mitchell’s deeper lead) sound like they’re crying until they combine together into—just that—the same release. Clever! That final stretch ranks among my favourite Mitchell “moments” ever, especially as it transitions perfectly into “The Same Situation.” “Car on a Hill” has more stunning vocal work when it enters the bridge, at the 1-minute mark as instruments swell into a tangle of voices.

The second half lets up a little by comparison. Sure, I wish that Joni Mitchell backed by fellow Canadian Robbie Robertson made something different than “Raised on Robbery,” but I like the song more than anything the Band crafted with Bob Dylan that same year: there’s an addicting pulse to the cadence of the lyrics, that Tom Scott’s solo rips, and there’s a thrill to the song that I don’t get often (see also: Taylor Swift’s “Getaway Car” for a similar vibe). As for “Twisted,” it feels like a bonus track that was tacked on, sure, and it’s Mitchell’s most overt jazz offering to-date, but it reminds me endlessly of “Nothing Like You” from Miles Davis’ Sorcerer.

Rolling Stone’s Stephen Holden wrote off The Hissing of Summer Lawns as “insubstantial music” as Mitchell turned her eyes to the alienation and hiss of suburbia many years before indie rock got there; it would be reclaimed as a classic years later and championed by none other than Prince. It’s a radical departure from her previous albums, not just as she dives deeper into jazz, but her singing and the songs themselves can be coolly detached. “In France They Kiss on Main Street” is the only song that was released as a single because it’s the only one that’s at all reminiscent of Court and Spark, and so of course, she dispatches of it immediately as the opener and then plunges listeners into one of the strangest songs of her career, stabilizing in a jazzy mid-tempo for the whole album afterwards. “In France They Kiss on Main Street” has the devastating lines “Under neon signs a girl was in bloom / And a woman was fading in a suburban room” that I think about every time I’m consciously aware of my own aging, but choruses full of repeated words is where the song shines, “Young love was kissing under bridges / Kissing in cars, kissing in cafés”: it really feels like an older person nostalgically reminiscing of sweeping through European cities while in love.

This drops into “The Jungle Line,” a song that mixes the ugliest tones anyone could possibly wrestle out of the Moog synthesizer—Mitchell was many things but she was not Stevie Wonder—with the Drummers of Burundi, an ensemble that Mitchell for some reason re-cast as “The Warrior Drums of Burundi.” I would like to champion the song as a very early example of a white artist being deeply invested in African music a decade ahead of Paul Simon and Peter Gabriel, but the sonics are hideous to juxtapose the primitive against the modern, and “The Jungle Line” set off, shall we say, an internal quest in Mitchell to find her black roots which culminated in donning blackface (not the only famous Canadian to do so). (Bon Iver does a similar one-two punch of a very pretty song into a very grotesque, rhythm-heavy one on 22, a Million.) The mid-tempo rest of the album has a few textural tricks up its sleeve, like Mitchell’s trilling voice—like a distant alarm—as a psychedelic hook on “Edith and the Kingpin” or the airplane landing drone that begins “Harry’s House / Centerpiece” that fades out into the jazz opener.

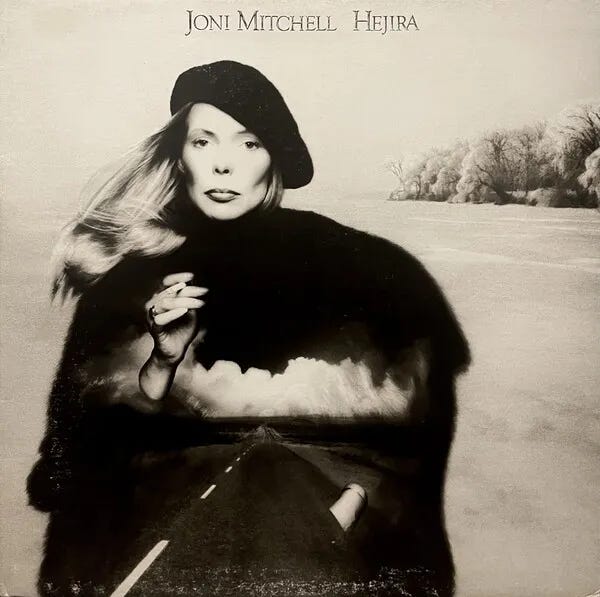

Hejira is Joni Mitchell’s last-great album. If you find yourself listening to this and not walking away with actual songs, that’s because the album is pure atmosphere. Written while traveling from Maine to Los Angeles, the album is the ultimate road album as made clear by the title (meaning ‘exodus’) and album cover. Except, unlike a lot of other albums that qualify as road albums, this is meant to be listened to alone, and where the physical destination matters less than just physically moving. This is a Long Drive for Someone With Nothing to Think About would’ve been another fitting title, had Mitchell been a 90s’ indie rock band. You are on a lonely road, and you are traveling, traveling, traveling, traveling; looking for something, what can it be?

Joni Mitchell hated the ‘dead, distant bass sound’ of the late-1960s and early-1970s, describing their strict reliance on the root of a chord as putting up “white picket fences” into her songs, so her friend suggested she work with jazz bassists instead. Yet working with Jaco Pastorius of all bassists is still a surprise, as his fretless bass has this digital sound that can seem at odds with the natural sounds of Joni Mitchell’s voice and guitar. But the pair work together well, to the point that all of these songs can be heard as conversations between Mitchell and Pastorius, and in that regard, an obvious influence on Kate Bush’s “Mother Stands for Comfort.” As Mitchell gets less and less interested in melodies, it’s over to Pastorius to act as both rhythm and melody, although I do wish her turn to jazz didn’t ditch dynamics; lord knows the albums from Hejira-onwards could’ve used more of those. There’s a few surprises in these songs, like the clarinet that wafts in the title track when she sings “Listen - strains of Benny Goodman / Coming through the snow and the pinewood trees” or Neil Young’s harmonica on “Furry Sings the Blues,” but they are not given the weight that the additional instruments that made For the Roses so magnificent.

The two best songs are the first two. “Coyote”’s off-hand mention of a “farmhouse burning down,” a passing image that’s immediately discarded as she “roll[s] right past that tragedy, struck me silly when I first heard it, so much that I wrote a poem (one of the very few poems that I wrote in my brief stint with poetry that I don’t look back on with total embarrassment) based on that one unimportant line in the middle of what is effectively a song about a man. The words “There’s no comprehending / Just how close to the bone and the skin and the eyes and the lips you can get / And still feel so alone / And still feel related”—especially with how she stresses the different body parts as she reminisces of a lover lingering on each—swim in my head at least weekly. (I do prefer the version she recorded with the Band for The Last Waltz if only because she gets to spit out some venom to the words, “He’s staring a hole in his scrambled eggs / He picks up my scent on his fingers / While he’s watching the waitresses’ legs” backed by a proper rock band.) The guitar chords of “Amelia” really do bring to mind the pale blue and vast skies that “swallowed” the famous pilot, or Mitchell’s own dreams of “747s over geometric farms”; the guitar tone is simply too warm and atmospheric for Mitchell to dwell too much on her recent heartache (“I wish that he was here tonight, it's so hard to obey / His sad request of me to kindly stay away”) or the tragic fate of Amelia Earhart. One negative: her words start getting worse from here on out; there’s a line on “Amelia” that strikes me as awkward because she knows she has to rhyme the line with “false alarm” but also needs to fit the meter, so she settles with alteration that’s frankly beneath her, “So this is how I hide the hurt as the road leads cursed and charmed.”

I didn’t care for these two mid-period albums when I first heard them, but I was in my early twenties at the time. I’m in my 30s now, and I find more to love in both The Hissing of Summer Lawns and Hejira with every passing year. Ultimately, I think of what the dearly-departed Doris Lessing said when criticizing how people consume literature, which is that they'll often read it at a point in their lives when it’s not meant to be read: “Remember that the book which bores you when you are 20 or 30 will open doors for you when you are 40 or 50 and vice versa. Don’t read a book that is out of its right time for you.” That goes for all art, and obviously music too.

Robert Christgau has the best put-down of Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, “This double album presents a real critic’s dilemma—I’m sure it’s boring, but I’m not sure how boring.” No worries, Bob, I’ll help you quantify: this is very boring. Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter is only twelve songs, so it’s not even like this is one of the many double albums where you can excise the filler and whittle it down to a single-disc playlist because you’d have to tighten the songs that stretch out, and the paradox is that doing so would lose what little charm those songs had to begin with. You certainly could lose “Overture - Cotton Avenue,” the near-seven minute opener that’s fatally boring despite the ‘rigorous’ arrangement of having six simultaneous guitars in different tunings and vocals. The fuck am I going on about? You wouldn’t even know that there were six guitars: it just wafts on forever, and doesn’t even give us the benefit of functioning like an overture of introducing the album’s melodies or motifs despite the name. While you’re at it, scotch “Talk To Me,” one of a few songs here that play like b-sides to Hejira; when Mitchell says “Chicken squawking” and starts imitating a chicken, my heart actually breaks. “Jericho” is fine, with Mitchell’s expressive way of playing alternative-tuned chords and letting them hang in the air. But is it worth the preceding 10 minutes? I don’t think so, and that’s the entire first side.

“Otis and Marlena”’s hook—”Muslims stick up Washington”—seems as problematic as the blackface album cover, but the drums that come in are deeply appreciative, as is the general character creation bringing back to her Ladies of the Canyon days that she seemed to leave behind as she turned the focus inwards in the interim. “Otis and Marlena” segues into “The Tenth World,” a six-minute percussion-led instrumental that you should hear once but will likely never need, which itself segues into “Dreamland.” These three songs form a unit that’s more cohesive and just as time-wasting as “Paprika Plains,” the 16-minute song that takes up the entire second side that feels prog-lite to me. Famously, this is Björk’s favourite album.

By Mitchell’s estimation, the label Asylum only pressed ten copies of Mingus because they assumed it was not going to be well-received by either pop or jazz audiences; Mitchell thought that jazzbos would accuse her of taking advantage of Mingus when his health was deteriorating despite the fact that it was Mingus was the one that approached her first. I think the reason why the label wouldn’t get behind this album was simpler: it’s a terrible album.

The big problem is that Joni Mitchell’s tribute album to one of the most inimitable, indomitable figures of jazz doesn’t sound like Charles Mingus at all. What’s particularly memorable about Charles Mingus is the sheer volume of sound: the raucous blues and blasts across his dizzying, Duke Ellington-inspired compositions held together by his thick, thick bass-lines. But Jaco Pastorius doesn’t play bass the way Mingus plays bass because Pastorius plays fretless, not double, and while he’s a master at his instrument, he’s not the right person to do Mingus. (Mingus was physically too sick from ALS to play bass, and the bass duties on his own album Me Myself and I that year were handled by Eddie Gomez, who would’ve been a more natural pick, and indeed, he was — except those tapes cut with Gomez were either lost or destroyed.) For another, Joni Mitchell doesn’t even try to adopt a Mingus-like maximalism, so what results feels like a batch of leftovers from Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter. Not helping is that Herbie Hancock isn’t allowed to do anything interesting outside of “Sweet Sucker Dance”; listening to this album, you’d have no idea you were in the presence of what might’ve been the greatest jazz pianist of the 1960s, but that had been true of the pianist for some time now in his own solo career. Another issue that no one talks about is that Mingus himself was no longer a great composer by this point, and lo, the album’s best song is the one that he doesn’t have a hand in: “God Must Be a Boogie Man” wherein Mitchell delivers the album’s most straight-forward (/only) hook in a funny call and response.

Wild Things Run Fast sees Mitchell looking at new wave for inspiration, but she’s not the front-man of a rock band, so the results are embarrassing AOR; my heart breaks in two from the opening measures of the title track alone, ditto “(You’re so Square (Baby, I Don't Care)”; for a better 50s’ throwback that year, I reach for Bruce Springsteen’s “Open All Night” or Fleetwood Mac’s “Oh Diane.” I don’t know what she was thinking with the hook of “Ladies Man.” “Chinese Cafe” is one of the few mentions of her daughter, whom she gave up for adoption in the mid-60s—“My child’s a stranger / I bore her / But I could not raise her”—which would become public knowledge when a former acquaintance sold the details to a tabloid magazine. Dog Eat Dog gets predictably deeper into 80s’ pop production by tapping none other than Thomas Dolby to help produce it; it should have been released one year later so it could’ve joined the bottoming out of basically all the other 60s’ legends at the same time (one exception: Paul Simon). (Even the cover looks strangely similar to that of Bob Dylan’s Knocked Out Loaded.) “Ethiopia” is one of those white saviour infomercial set to songs—see also: the Northern Lights’ single she was involved with that same year—and though I appreciate in theory her sonic experiments like waving around a metal sheet on “The Three Great Stimulants” as if she were Sun Ra, the production never lets any sonics shine. The bass on “Good Friends” always makes me think of Bon Jovi’s “Livin’ on a Prayer” which, I know, was released afterwards, but still makes me shudder because at no point in listening to a Joni Mitchell song should I be thinking of Bon Jovi. Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm does the late-80s thing of surrounding its lead artist with as many features that the label could pay for—see also: Aretha Franklin’s Through the Storm—and is almost as appalling as Dog Eat Dog but slightly better. “My Secret Place” has some real clunkers of rhymes (“Colorado… street bravado… girl meets desperado”), and neither Peter Gabriel’s appearance there nor Willie Nelson’s appearance on “Cool Water” amount to enough: it’s like they poke their heads in and out of the song continuously in a detracting way.

Night Ride Home, released in 1991, was hailed as some sort of comeback for her simply because it switched out the 80s’ production for a quieter, more natural sound—i.e. what Daniel Lanois did for Bob Dylan on Oh Mercy but without any of the production auteurship—and the title recalled Hejira in that it evoked road and movement. In actuality, it was her second-worst album at the time; Larry Klein’s bass playing is exactly what she meant when she talked about non-jazz bassists putting up “white picket fences” and stifling her, but I guess it’s different when it’s your husband erecting the walls. Turbulent Indigo contains her worst lyrics ever in “His license plate / It said ‘Just Ice’ / Is justice just ice?” Naturally, she won a Grammy for it. It’s a hot take but not one that I would hurt myself over, but I think Taming the Tiger is the best of these three albums because texturally, there’s simply more going on than the endless gentle pings from Larry Klein whom she divorced in 1994. For her final album of the decade, she discovered the digital guitar processor Roland VG-8 whose output sounded like, well, a digital guitar. On the one hand, it is heartbreaking to hear one of the greatest and most innovative guitar players feed her guitar into a sterilized machine, but it’s still interesting and reminds me of her previous sonic experiments when she started going melodically bankrupt. Opener “Harlem in Havana” has Wayne Shorter adding wafts of melody against a backdrop of digital chimes and samples that sounds like akin to some songs from R.E.M.’s Up that same year. Like Night Ride Home’s “Cherokee Louise,” where she sang about an abused indigenous girl, there’s a song here about American soldiers raping Japanese women overseas, but the music is so fucking pleasant that you wouldn’t even notice. But maybe that’s preferable to the preceding “Lead Balloon” where she ‘rocks out.’ All told, her three albums from the 90s are actually worse than her three albums from the 80s because boring is its own version of bad.

She released an album of traditional pop covers Both Sides Now and then a double album of orchestral renditions of her catalogue on Travelogue that was supposed to be her goodbye to recording, both moves reeking of “I’m getting too old for this shit.” I miss her guitar playing—she declines to bother on either—and her voice isn’t the same: though Mitchell was adamant that her love for cigarette smoking wasn’t the cause, it certainly didn’t help the aging process. Joni Mitchell was correct that critics within the pop/rock sphere didn’t take well to artists aging nearly as well as jazz audiences did, but her embrace of jazz in the mid-70s didn’t carry forward enough after Mingus; these two albums are exceptions that prove the rule.

She emerged out of retirement with mediocrity, Jay-Z-style, with Shine, an album inspired out of political strife but sounds like more of the lounge jazz-pop of her 90s’ era with some of her most insipid lyrics. The album is full of clichés, like how America is imagined as a place with an “Eagle at the top of a tree” on “This Place” while also thinking how no American would dare to kill a roaming black bear on their territory (you sure about that Joni?). “If I Had a Heart”—“If I had a heart, I’d cry”; oh shut up: I’ve heard all of your music, I know you have a heart—dares to ponder what’s so holy about a holy war while rhyming genocide with suicide. No surprise that the best song is the instrumental, and the worst one is the re-make.

In 2015, Mitchell suffered a brain aneurysm, so it seemed like her music-making days were over for good. She surprised everyone after re-learning how to play guitar and sing by appearing at the Newport Folk Festival in 2022 with her first concert in over two decades supported by younger musicians, released the following year as At Newport. Had it just been Mitchell and the backing musician—that include Marcus Mumford and his pal Blake Mills—then it would be a feel-good concert that wouldn’t be worth wasting any ink over. But Brandi Carlile is one tequila shot from interjecting “YAS QUEEN” in every song; she can’t help herself from going “Tell ‘em, Joni! Everyday!” (“Both Sides Now”) and “Kick ass, Joni Mitchell!” (“Just Like This Train”) or whispering words needlessly (“Amelia”) as if she’s not convinced Mitchell can sing them by herself, even though her voice is actually surprisingly graceful for someone near eighty. Did Mitchell pity Carlile and just let her do her thing?

Truth be told, I find none of Joni Mitchell’s live albums essential. Recorded and released after Court and Spark, Miles of Aisles functions wonderfully as a greatest hits compilation, sure, but to me, it’s her waving good-bye to her past: she’s testing out jazzifying these compositions without going full-tilt yet to mixed results, and I assuredly don’t like the funk groove added to “Woodstock” or the reggae one behind “Carey.” Shadow and Light is a double album performed by the Mingus band with Pet Metheny on guitar. The version of “The Dry Cleaner from Des Moines” climaxes with keyboardist Lyle Mays hitting the same note over and over that enables Michael Brecker to soar, and though I miss the overdubbed Mitchell hook on “Edith and the Kingpin,” I really adore when Mitchell sings that the “band sounds like typewriters,” the band behind her make a clicking groove to imitate it. Most of the songs are slow and laboured over; I wonder if anyone in the audience was disappointed when—nearing the end of the set—Mitchell announced enthusiastically that she would “rock and roll” them, only to launch into a cover of a 50s tune, and then immediately hit them with a 5-minute a capella song afterwards. Metheny gets in a good solo that I’ll never think about after typing this sentence, and his tone on the Hejira songs don’t have the same atmosphere as the studio version.

It’s interesting: my problem with Joni Mitchell is the exact opposite of the problem I have with Neil Young. When Mitchell figured out that jazz was kinder to aging musicians, she turned her back on her folk era, evidenced by the fact that her early years are barely represented in Shadow and Light and not at all represented in her appearance on the Band’s The Last Waltz. Meanwhile, I find Neil Young emptying the floodgates on his past exhausting to keep up with — not that I have, mind you, I hopped off the nostalgia train after Homegrown. The twin pillars of Canadiana, on such extreme opposites!

I’m headed off to Calgary next week, two hours north of Fort Macleod where Mitchell was born and where she did her first paid gigs before moving to Toronto, so I couldn’t think of a better time to revisit mostly weird and mostly wonderful discography.

Song to a Seagull - B+ Clouds - B+ Ladies of the Canyon - A- Blue - A+ For the Roses - A Court and Spark - A Miles of Aisles - B+ The Hissing of Summer Lawns - A- Hejira - A- Don Juan's Reckless Daughter - B- Mingus - C+ Shadows and Light - B- Wild Things Run Fast - C+ Dog Eat Dog - C+ Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm - C+ Night Ride Home - C+ Turbulent Indigo - C+ Taming the Tiger - C+ Both Sides Now - B- Travelogue - B- Shine - C+ At Newport - D

![Cover art for Joni Mitchell [Song to a Seagull] by Joni Mitchell Cover art for Joni Mitchell [Song to a Seagull] by Joni Mitchell](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!yVKT!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb1990453-909b-44b9-8456-0a3a4b121cd5_600x606.webp)

Excellent and thorough examination of Joni’s work. I agree with you that Hissing and Hejira get better and better as you age, like it’s waiting for you to catch up to everything they’re saying. We’ll agree to disagree about Night Ride Home, and throwing a Modest Mouse reference in there was pure gold. Great read!

Thanks for this about my all time fave singer songwriter. I agree with your album rankings. So knowledgeable from someone so young! I was a teen when I bought her first album and frequented Laurel Canyon back then. Though too young to get into too much trouble unfortunately.